Heart Sutra

| Prajnaparamita sutras |

|---|

| Selected short sutras |

| Medium length sutras |

|

| Long sutras |

|

The Heart of Transcendent Wisdom (Skt. prajñāpāramitā hṛdaya), commonly known as the Heart Sutra, is one of the most important texts within the Sanskrit Mahayana tradition. It is said to present the heart, or the essence, of the Prajnaparamita teachings, which are the definitive teachings on the Mahayana view of the interdependent nature of reality.

The Prajnaparamita teachings as a whole comprise a large corpus of literature, including sutras of great length, and many commentaries by great masters of India, East Asia and Tibet. These teachings are revered within the Mahayana tradition as representing the highest, most subtle view of the nature of reality. The Heart Sutra, which is no more than a page in length, presents an essential summary of this view.

The Heart Sutra is the most well-known and most commonly recited Mahayana sutra, particularly in East Asia, where it is common for monks and lay practitioners to recite the Heart Sutra daily. Thupten Jinpa writes: “Even today, the chanting of this sutra can be heard in Tibetan monasteries, where it is recited in the characteristically deep overtone voice, in Japanese Zen temples, where the chanting is done in tune with rhythmic beating of a drum, and in Chinese and the Vietnamese temples, where it is sung in melodious tunes.”[1]

Title

The sutra is known by the following titles in the canonical languages:

- Sanskrit: Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya

- Chinese: Bore boluomiduo xin jing, 般若波羅蜜多心經

- Tibetan: Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa’i snying po, ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པའི་སྙིང་པོ་

The full title is translated into English as:

- The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra (Buswell)

- The Sutra of Transcendent Wisdom (Nalanda Translation Committee)

- The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, the Blessed Mother (84000)

- The Heart of the Transcendent Perfection of Wisdom (Dharmachakra Translation Committee, Pearcey)

The short title in English is:

- Heart Sutra

Historical versions of the title

Despite the common name Heart Sūtra, the word sūtra is not present in known Sanskrit manuscripts.[2] A version by the Chinese translator Xuanzang was the first to call the text a sutra. No extant Sanskrit copies use this word, though it has become standard usage in Chinese and Tibetan, as well as English.[3]

There are also alternate versions of the title within the different Chinese translations:

- The Zhi Qian version is titled Po-jo po-lo-mi shen-chou i chuan[4] or Prajnaparamita Dharani;[5]

- The Kumarajiva version is titled Mo-ho po-jo po-lo-mi shen-chou i chuan[4] or Maha Prajnaparamita Mahavidya Dharani.

- The Xuanzang version was the first to use Hrdaya or "Heart" in the title.[6]

Some citations of Zhi Qian's and Kumarajiva's versions prepend moho (which would be maha in Sanskrit) to the title. Some Tibetan editions add bhagavatī, meaning "Victorious One" or "Conqueror", an epithet of Prajnaparamita as goddess.[7]

Text

There are two versions of the Heart Sutra text: a long version and a short version. Both versions are less than one page in length. The difference between the versions is that the long version includes brief introductory and concluding sections. According to the Princeton Dictionary, “the longer version is better known in India and the short version better known in East Asia."[8]

Sanskrit language

Both long and short versions exist in Sanskrit.[2]

Chinese language

The Chinese Canon includes both long and short versions.[2]

Tibetan language

The Tibetan Canon includes the long version of the text (in the Prajnaparamita section of the Kangyur.)[9]

English translations available online

Translations from the Chinese language

- "The Shorter Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sūtra". Lapis Lazuli Texts. From the Chinese translation by Xuanzang (T08n251).

- "The Longer Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sūtra". Lapis Lazuli Texts. From the Chinese translation by Prajñā (T08n253).

- "The Heart of Prajna Paramita Sutra". Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. From the Chinese translation by Tang master Hsüan-Tsang

Translations from the Tibetan language

The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, the Blessed Mother

The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, the Blessed Mother Heart Sutra, Lotsawa House

Heart Sutra, Lotsawa House Heart_Sutra, Rangjung Yeshe Wiki

Heart_Sutra, Rangjung Yeshe Wiki- "The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom". LamRim.com.

English translation from Dharmachakra Translation Committee

The following English translation of the long version of the Heart Sutra is from an edition of the Tibetan Canon.

Translated by the Dharmachakra Translation Committee under the patronage and supervision of "84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha."

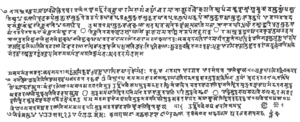

Source text: ![]() The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, the Blessed Mother

The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, the Blessed Mother

The Heart of the Transcendent Perfection of Wisdom

1.1

Homage to the Perfection of Wisdom, the Blessed Mother!

Thus did I hear at one time. The Blessed One was residing on Vulture Peak Mountain at Rājagṛha together with a great saṅgha of monks and a great saṅgha of bodhisattvas.

1.2

At that time the Blessed One rested in an absorption on the categories of phenomena called illumination of the profound.

1.3

At the same time, the bodhisattva great being, noble Avalokiteśvara, while practicing the profound perfection of wisdom, looked and saw that the five aggregates are also empty of an intrinsic nature.

1.4

Then, due to the Buddha’s power, venerable Śāriputra asked the bodhisattva great being, noble Avalokiteśvara, “How should sons of noble family or daughters of noble family train if they wish to engage in the practice of the profound perfection of wisdom?”

1.5

The bodhisattva great being, noble Avalokiteśvara, replied to venerable Śāradvatīputra, “Śāriputra, sons of noble family or daughters of noble family who wish to engage in the practice of the profound perfection of wisdom should see things in this way: they should correctly observe the five aggregates to be empty of an intrinsic nature.

1.6

“Form is empty. Emptiness is form. Emptiness is not other than form, and form is also not other than emptiness. In the same way, feeling, perception, formation, and consciousness are empty.

1.7

“Śāriputra, therefore, all phenomena are emptiness; they are without characteristics, unborn, unceasing, without stains, without absence of stains, not deficient, and not complete.

1.8

“Śāriputra, therefore, in emptiness there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no formations, no consciousness, no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind, no form, no sound, no smell, no taste, no texture, and no mental object.

1.9

“There is no element of the eye, up to no element of the mind, and further up to no element of the mind consciousness.

1.10

“There is no ignorance and no exhaustion of ignorance, up to no aging and death and no exhaustion of aging and death.

1.11

“There is no suffering, no origin of suffering, no cessation of suffering, no path, no wisdom, no attainment, and no nonattainment.

1.12

“Śāriputra, therefore, since bodhisattvas have no attainment, they rely upon and dwell in the perfection of wisdom Because their minds have no veils, they have no fear. Having utterly gone beyond error, they reach the culmination of nirvāṇa.

1.13

“All the buddhas who reside in the three times have likewise fully awakened to unsurpassed and perfect awakening by relying upon the perfection of wisdom.

1.14

“Therefore, the mantra of the perfection of wisdom is the mantra of great knowledge, the unsurpassed mantra, the mantra that is equal to the unequaled, and the mantra that utterly pacifies all suffering. Since it is not false, it should be known to be true.

1.15

“The mantra of the perfection of wisdom is stated thus:

tadyathā gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā

1.16

“Śāriputra, this is the way a bodhisattva great being should train in the profound perfection of wisdom.”

1.17

Then the Blessed One arose from that absorption and gave his approval to the bodhisattva great being, noble Avalokiteśvara, saying, “Excellent! Excellent! Son of noble family, it is like that. Son of noble family, it is like that. The profound perfection of wisdom should be practiced just as you have taught, and even the thus-gone ones will rejoice.”

1.18

When the Blessed One had said this, venerable Śāradvatīputra,58 the bodhisattva great being, noble Avalokiteśvara, and the entire assembly, as well as the world with its devas, humans, asuras, and gandharvas, rejoiced and praised what the Blessed One had said.

1.19

This completes The Great Vehicle Sūtra “The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom, the Blessed Mother.”

Brief explanation

The main part of the (longer version of the) sutra begins when the Buddha, with his students gathered around him, enters into a state of deep meditation. At this time, his disciple Avalokiteshvara experiences a profound insight into the empty nature of all phenomena.

Then Shariputra, another close disciple of the Buddha, asks Avalokiteshvara: "How should someone train if they wish to engage in the practice of prajnaparamita?” He is asking, in other words, "How can I practice these teachings (on prajnaparamita) in order to realize the true nature of things?"

In response to Shariputra, Avalokiteshvara describes the "true nature of things" by referring to specific sets of phenomena that are described in the Abhidharma teachings.[10] Thus, Avalokiteshvara explains emptiness in terms of:

- the five skandhas,

- the twelve ayatanas, and

- the eighteen dhatus.

In the Abhidharma teachings, each of the above sets of phenomena are used to illustrate the impermanent, compounded nature of all phenomena. However, the early Abhidharma scholars still posited the existence of ultimately real mental and physical factors called dharmas. In regards to the physical factors, the early Abhidharma theory was similar to the Western theory of the "atom." The Abhidharma theory described the physical factors as indivisible particles that were the "building blocks" of all other phenomena.

Thus, in reference to the skandha of form (rupa), meaning physical matter, Avalokiteshvara states:

- Form is empty. Emptiness is form.

In this famous statement, Avalokiteshvara refutes the existence of even the atomic-sized physical particles described in the Abhidharma. He is asserting that there are no "building blocks" of physical matter; there is no smallest particle. All of phenomena is lacking inherent existence (svabhāva); thus all things are empty (śūnyatā) in nature.

Avalokiteshvara goes on to state:

- In emptiness, there is no form...

Here, Avalokitishvara is not saying that "form" (rupa) doesn't exist. His meaning is that when you analyze "form" on the deepest level, according to the logic of the Prajnaparamita teachings, you find there is no inherent existence (svabhāva). Thus while form appears to be solid and lasting, on the ultimate level, the true nature of all form is that things appear, yet they are empty--like a magicians trick, a mirage, or a sand castle in sky. (See Eight similes of illusion.)

Avalokiteshvara continues:

- [there is] no sensation, no recognition, no conditioning factors, no consciousness

Here, Avalokiteshvara is saying the the remaining skandhas within the "five skandhas," the mental factors, also lack inherent existence. The nature of these mental factors is empty.

Avalokiteshvara continues:

- In reference to the twelve ayatanas:

- ... [there is] no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no visible form, no sound, no odour, no taste, no texture and no mental objects

- In reference to the eighteen dhatus:

- There is no element of the eye, up to no element of the mind, and further up to no element of the mind consciousness.

In the above statements, Avalokiteshvara is pointing to the empty nature of all the constituents of reality. He then goes on to assert the emptiness of the twelve links of dependent origination and the Four Noble Truths.

Thus, Avalokiteshvara states, the bodhisattva relies on the perfection of wisdom teachings, which present the highest, most subtle view of the nature of reality--that all phenomena are completely empty of inherent existence.

Avalokiteshvara concludes by reciting the Heart Sutra mantra, which is considered a condensation of the perfection of wisdom teachings.

The Buddha then arises from meditation and praises the words of Avalokiteshvara.

Mantra

The Heart Sūtra mantra is:

- Sanskrit: gate gate pāragate pārasaṃgate bodhi svāhā

- Chinese: 揭諦揭諦 波羅揭諦 波羅僧揭諦 菩提娑婆訶

- Tibetan: ག༌ཏེ༌ག༌ཏེ༌པཱ༌ར༌ག༌ཏེ༌པཱ༌ར༌སཾ༌ག༌ཏེ༌བོ༌དྷི༌སྭཱ༌ཧཱ།

The mantra has been translated into English as:

- “Go, go, go beyond, go totally beyond, be rooted in the ground of enlightenment.”[11]

Meaning of the mantra in the Tibetan tradition

The 14th Dalai Lama provides the following explanation of the mantra from the Tibetan Buddhist point of view:

- Thus, the entire mantra itself can be translated as “Go, go, go beyond, go totally beyond, be rooted in the ground of enlightenment.” We can interpret this mantra metaphorically to read “Go to the other shore,” which is to say, abandon this shore of samsara, unenlightened existence, which has been our home since beginningless time, and cross to the other shore of final nirvana and complete liberation.[11]

Regarding the implicit meaning of the mantra, the Dalai Lama states:

- The mantra contains the implicit, or hidden, meaning of the Heart Sutra, revealing how the understanding of emptiness is related to the five stages of the path to buddhahood.[11]

In this context, the mantra is said to represent the progressive steps along the Five Paths of the Bodhisattva, through the two preparatory stages (the path of accumulation and preparation – gate, gate), through the first part of the first bhumi (path of insight – pāragate), through the second part of the first to the tenth bhumi (path of meditation – Pārasamgate), and to the eleventh bhumi (stage of no more learning – bodhi svāhā).

The Princeton Dictionary states: "the presence of the mantra in the sūtra has led to its classification as a tantra rather than a sutra in some Tibetan catalogues..."[8]

The mantra in the East Asian tradition

According to Jan Nattier, in the Chinese Canon, this mantra in is present in several variations associated with several different Prajñāpāramitā texts.[12]

Relation to the Abhidharma

Contemporary scholar Richard K. Payne states:

- Abhidharma thought constitutes the conceptual backbone of the entirety of the Buddhist tradition. An example that is probably familiar to many religious studies scholars is the Heart Sutra. In addition to finding its way into many religious studies textbooks, this is widely known and recited in many East Asian Buddhist traditions. Indeed it is chanted daily in some temples, or recited continuously by Buddhist adherents on pilgrimage. However, in addition to such ritual or devotional uses, it can be read as a concise Mahāyāna commentary on the ontological status of abhidharma categories. One of the perhaps most quoted lines from the Heart Sutra—“form is emptiness, emptiness is form”—is not an isolated assertion that can be addressed on its own. It is instead the first of a long list of abhidharma categories the independent existence of which is being denied. That context is key to understanding the significance of the line.[13]

Dating and origins

Earliest extant versions

The earliest extant dated text of the Heart Sutra is a stone stele dated to 661 CE located at Yunju Temple and is part of the Fangshan Stone Sutra. It is also the earliest copy of Xuanzang's 649 CE translation of the Heart Sutra (Taisho 221); made three years before Xuanzang passed away.[14][15][16][17]:12,17[note 1]

A palm-leaf manuscript found at the Hōryū-ji Temple is the earliest undated extant Sanskrit manuscript of the Heart Sutra. It is dated to c. 7th–8th century CE by the Tokyo National Museum where it is currently kept.[18][19]

Origin of the Heart Sutra

According to traditional accounts, the Heart Sūtra was composed by a Sarvastivadan monk in the 1st century CE in Kushan Empire territory, and it was first translated into Chinese in approximately 200-250CE.

However, there is currently a lack of scholarly consensus on the original author and origin of the Heart Sutra. Contemporary scholar Jan Nattier (1992) theorizes (based on her study of Chinese and Sanskrit texts) that the Heart Sutra may have initially been composed in China.[12]

Other scholars, such as Fukui, Harada, Ishii and Siu, based on their study of Chinese and Sanskrit texts of the Heart Sutra and other medieval period Sanskrit Mahayana sutras, theorize that the Heart Sutra could not have been composed in China but was composed in India.[20][21][note 2][22][23][24]:43–44,72–80

Theory of Sarvistavadan origin

The specific sequence of concepts listed in lines 12-20 ("...in emptiness there is no form, no sensation, ... no attainment and no non-attainment") is the same sequence used in the Sarvastivadin Samyukta Agama; this sequence differs in the texts of other sects. On this basis, Red Pine has argued that the Heart Sūtra is specifically a response to Sarvastivada teachings that dharmas are real.[25]

Also, Avalokiteśvara addresses Śariputra, who was, according to the scriptures and texts of the Sarvastivada and other early Buddhist schools, the promulgator of abhidharma, having been singled out by the Buddha to receive those teachings.[26]

Theory of role of Avalokiteśvara

It is unusual for Avalokiteśvara to be in the central role in a Prajñāpāramitā text. Early Prajñāpāramitā texts involve Subhuti, who is absent from both versions of the Heart Sūtra, and the Buddha who is only present in the longer version.[27] Jan Nattier considers this as evidence that the text is Chinese in origin.[12]

Gallery

Sanskrit text of the Heart Sūtra, in the Siddhaṃ script. Replica of a palm-leaf manuscript dated to 609 CE.

Chinese text of the Heart Sūtra, by scholar and calligrapher Ouyang Xun, dated 635 CE.

Chinese text of the Heart Sūtra, by Yuan Dynasty artist and calligrapher Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322 CE).

Notes - long

- ↑ He and Xu:

On page 12 "Based on this investigation, this study discovers ... the 661 CE Heart Sutra located in Fangshan Stone Sutra is probably the earliest extant "Heart Sutra"; [another possibility for the earliest Heart Sutra,] the Shaolin Monastery Heart Sutra commissioned by Zhang Ai on the 8th lunar month of 649 CE [Xuanzang's translated the Heart Sutra on the 24th day of the 5th lunar month in 649 CE][17]:21 mentioned by Liu Xihai in his unpublished hand written draft entitled "Record of Engraved Stele's Surnames and Names", [regarding this stone stele, it] has so far not been located and neither has any ink impressions of the stele. It's possible that Liu made a regnal era transcription error. (He and Xu mention there was a Zhang Ai who is mentioned in another stone stele commissioned in the early 8th century and therefore the possibility Liu made a regnal era transcription error;however He and Xu also stated the existence of the 8th century stele does not preclude the possibility that there could have been two different persons named Zhang Ai.)[17]:22–23 The Shaolin Monastery Heart Sutra stele awaits further investigation."[17]:28

On page 17 "The 661 CE and the 669 CE Heart Sutra located in Fangshan Stone Sutra mentioned that "Tripitaka Master Xuanzang translated it by imperial decree" (Xian's Beilin Museum's 672 CE Heart Sutra mentioned that "Śramaṇa Xuanzang translated it by imperial decree"..." - ↑ Harada's cross-philological study is based on Chinese, Sanskrit and Tibetan texts.

References

- ↑ Tenzin Gyatso 2015, Editor's Preface.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Nattier 1992, p. 200.

- ↑ Pine 2004, pg. 39

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nattier 1992, p. 183.

- ↑ Pine 2004, pg. 20

- ↑ Pine 2004, pg. 36

- ↑ Pine 2004, pg. 35

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayasūtra.

- ↑

Perfection of Wisdom

Perfection of Wisdom

- ↑ According to the Sarvastivada and other early Buddhist schools, Shariputra was a promulgator of Abhidharma teachings.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Tenzin Gyatso 2015, p. 131.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Nattier 1992.

- ↑ Text, History, and Philosophy: Abhidharma across Buddhist Scholastic Traditions, Book Review by Richard K. Payne

- ↑ Ledderose, Lothar (2006). "Changing the Audience: A Pivotal Period in the Great Sutra Carving Project". In Lagerway, John. Religion and Chinese Society Ancient and Medieval China. 1. The Chinese University of Hong Kong and École française d'Extrême-Orient. p. 395.

- ↑ Lee, Sonya (2010). "Transmitting Buddhism to A Future Age: The Leiyin Cave at Fangshan and Cave-Temples with Stone Scriptures in Sixth-Century China". Archives of Asian Art. 60.

- ↑ 佛經藏經目錄數位資料庫-般若波羅蜜多心經 [Digital Database of Buddhist Tripitaka Catalogues-Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayasūtra]. CBETA (in 中文).

【房山石經】No.28《般若波羅蜜多心經》三藏法師玄奘奉詔譯 冊數:2 / 頁數:1 / 卷數:1 / 刻經年代:顯慶六年[公元661年] / 瀏覽:目錄圖檔 [tr to English : Fangshan Stone Sutra No. 28 "Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Sutra" Tripitaka Master Xuanzang translated by imperial decree Volume 2, Page 1 , Scroll 1 , Engraved 661 CE...]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 He 2017

- ↑ e-museum 2018 Ink on pattra (palmyra leaves used for writing upon) ink on paper Heart Sutra: 4.9x28.0 Dharani: 4.9x27.9/10.0x28.3 Late Gupta period/7–8th century Tokyo National Museum N-8'

- ↑ Nattier 1992, pp. 208-209.

- ↑ Harada 2002.

- ↑ Harada 2010

- ↑ Fukui 1987.

- ↑ Ishii 2015.

- ↑ Siu 2017.

- ↑ Pine 2004, pg. 9

- ↑ Pine 2004, pp. 11-12, 15

- ↑ Nattier 1992, p. 156.

Sources

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University- Fukui Fumimasa 福井 文雅 (1987) (in Japanese). Hannya shingyo no rekishiteki kenkyu 般若心経の歴史的研究. 東京: Shunjusha 春秋社. ISBN 4-393-11128-1

- Harada, Waso (原田 和宗) (2002). 梵文『小本・般若心経』和訳 [An Annotated Translation of The Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya] (in 日本語). Association of Esoteric Buddhist Studies. pp. L17–L62.

- Harada, Waso (原田 和宗) (2010). 「般若心経」の成立史論」 [History of the Establishment of Prajñāpāramitāhṛdayasūtram] (in 日本語). Tokyo: Daizō-shuppan 大蔵出版. ISBN 9784804305776.

- Ishii, Kōsei (石井 公成) (2015). 『般若心経』をめぐる諸問題 : ジャン・ナティエ氏の玄奘創作説を疑う [Issues Surrounding the Prajñāpāramitā-hṛdaya: Doubts Concerning Jan Nattier’s Theory of a Composition by Xuanzang] (in 日本語). 64. Translated by Kotyk, Jeffrey. 印度學佛教學研究. pp. 499–492. English translation --> [1]

- Luk, Charles. The Secrets of Chinese Meditation (1991) Samuel Weiser. ISBN 978-0877280668

- Nattier, Jan (1992), "The Heart Sūtra: A Chinese Apocryphal Text?", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 15 (2): 153–223

- Pine, Red. The Heart Sutra: The Womb of the Buddhas (2004) Shoemaker 7 Hoard. ISBN 1-59376-009-4

- Tenzin Gyatso (2015), Jinpa, Thubten, ed., Essence of the Heart Sutra, Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications

- Wayman, Alex. 'Secret of the Heart Sutra.' in Buddhist insight: essays Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1990. pp. 307–326. ISBN 81-208-0675-1.

Further reading

- Geshe Sonam Rinchen. Heart Sutra: An Oral Commentary, Snow Lion Publications

- Conze, Edward (translator) (1984). Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines & Its Verse Summary. Grey Fox Press. ISBN 978-0877040491.

- Conze, Edward. Buddhist Wisdom Books: Containing the "Diamond Sutra" and the "Heart Sutra" (New edition). Thorsons, 1975. ISBN 0-04-294090-7

- Conze, Edward. Prajnaparamita Literature (2000) Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers ISBN 81-215-0992-0 (originally published 1960 by Mouton & Co.)

- Lopez, Donald (1990). The Heart Sutra Explained. South Asia Books. ISBN 978-8170302384.

- Nhat Hanh, Thich (1988). The Heart of Understanding. Berkeley, California: Parallax Press. ISBN 978-0938077114.

- Porter, Bill (Red Pine) (2004-08-31). The Heart Sutra: The Womb of Buddhas. Shoemaker & Hoard. ISBN 978-1593760090.

- Waddell, Norman (1996-07-15). Zen Words for the Heart: Hakuin's Commentary on the Heart Sutra. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala. ISBN 978-1570621659.

- The Dalai Lama (2005). Essence of the Heart Sutra:The Dalai Lama's Heart of Wisdom Teachings. Boston Massachusetts: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-284-7

- Hasegawa, Seikan (1975). The Cave of Poison Grass: Essays on the Hannya Sutra. Arlington, Virginia: Great Ocean Publishers. ISBN 0-915556-00-6.

- Fox, Douglass (1985). The Heart of Buddhist Wisdom: A Translation of the Heart Sutra With Historical Introduction and Commentary. Lewiston/Queenston Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-053-1.

External links

Discourses

- "Master Hsing Yun at UWest - Class 1A". Retrieved 2008-03-22. A YouTube video of a 47-minute discourse by Hsing Yun

- Dr. Yutang Lin: The Unification of Wisdom and Compassion

| This article includes content from the May 2014 revision of Heart Sutra on Wikipedia ( view authors). License under CC BY-SA 3.0. |