Milindapañha

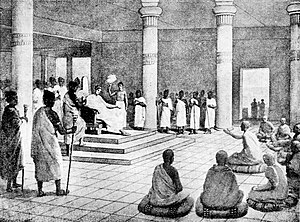

The Milindapañha ("Questions of Milinda") is a text from the Pali Canon that records a dialog between the Buddhist sage Nagasena and Bactrian-Greek King Milinda (a.k.a Menander I).

John Kelly states:

- Composed around the beginning of the Common Era, and of unknown authorship, the Milindapañha is set up as a compilation of questions posed by King Milinda to a revered senior monk named Nagasena. This Milinda has been identified with considerable confidence by scholars as the Greek king Menander of Bactria, in the dominion founded by Alexander the Great, which corresponds with much of present day Afghanistan. Menander's realm thus would have included Gandhara, where Buddhism was flourishing at that time.

- What is most interesting about the Milindapañha is that it is the product of the encounter of two great civilizations — Hellenistic Greece and Buddhist India — and is thus of continuing relevance as the wisdom of the East meets the modern Western world. King Milinda poses questions about dilemmas raised by Buddhist philosophy that we might ask today.[1]

The questions asked by King Milinda cover a wide range of topics,[2] "such as the nature of self, wisdom and desire, transmigration, karma, the Buddha as a historical figure, the Buddhist Order, the qualifications of monks, the respective roles of monks and lay people, and nirvana."[3]

In the discussion on the nature of "self," Nagasena refers the simile of the chariot to explain the Buddhist concept of the not-self (anatman). Just as the chariot is not one singular independent thing, but it is composed of parts, in the same way, that which we call the "self" (atman) is not a singular independent entity, but it is likewise composed of parts.

Text

The Milinda Pañha is included in the the Khuddaka Nikaya of the Burmese version of the Pali Canon.[1]

The text is not included in the Thai or Sri Lankan versions of the Pali Canon. However, the surviving Theravāda text is in Sinhalese script.

An abridged version of the text is included in the Chinese Canon, with the title the Monk Nāgasena Sutra (*Nāgasenabhikṣusūtra). The Chinese version corresponds to the first three chapters of the Pali Milindapanha.[4][3] It was translated into the Chinese language sometime during the Eastern Jin dynasty (317–420).[3]

Textual history

The Princeton Dictionary states:

- The text was presumably composed in northern India in Sanskrit or Prakrit and later translated into Pāli, with the original composition or compilation probably occurring around the beginning of the Common Era. (There is an early Chinese translation made around the late fourth century, probably from a Central Asian recension in Gāndhārī titled the *Nāgasenabhikṣusūtra, which is named after the bhikṣu Nāgasena rather than King Milinda.)[2]

Oskar von Hinüber (2000) states that that the work is likely a composite, with additions made over some time.[5] In support of this, he notes that the Chinese versions of the work are substantially shorter.[6]

von Hinüber states the earliest part of the text was likely written between 100 BCE and 200 CE.[7] He also states that the text's original language might have been Gandhari, based on language, vocabulary and some concepts in the extant Chinese translation.[8]

According to von Hinüber, the text includes anachronisms, and the dialogue lacks any sign of Greek influence but instead is traceable to the Upanisads.[9]

Thomas Rhys Davids stated:

- The Questions of Milinda is undoubtedly the masterpiece of Indian prose, and indeed is the best book of its class, from a literary point of view, that had then been produced in any country.[10]

The conversion of King Milinda

In the text, Milinda (Menander) is introduced as the "[k]ing of the city of Sāgala in India, Milinda by name, learned, eloquent, wise, and able". Buddhist tradition relates that, following his discussions with Nāgasena, Milinda adopted the Buddhist faith "as long as life shall last"[11] and then handed over his kingdom to his son to retire from the world.[11]

Contents

For a table of contents for the Milindapañhā, see:

Translations

The following English translations are available:

Milindapañha, SuttaCentral - online version of the 1894 Rhys Davids translation, lightly edited by Bhikkhu Sujato

Milindapañha, SuttaCentral - online version of the 1894 Rhys Davids translation, lightly edited by Bhikkhu Sujato- T. W. Rhys Davids (trans.), "Questions of King Milinda", Sacred Books of the East, volumes XXXV & XXXVI, Clarendon/Oxford, 1890–94; reprinted by Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- I. B. Horner (trans.), Milinda's Questions, 1963-4, 2 volumes, Pali Text Society, Bristol (reprinted in 1990 by the Pali Text Society)

Abridgements include:

John Kelly (2005), Milindapañha: The Questions of King Milinda (excerpts), Access to Insight

John Kelly (2005), Milindapañha: The Questions of King Milinda (excerpts), Access to Insight- Pesala, Bhikkhu (ed.), The Debate of King Milinda: An Abridgement of the Milindapanha. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1992. Based on Rhys Davids (1890, 1894).

- Mendis, N.K.G. (ed.), The Questions of King Milinda: An Abridgement of the Milindapanha. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, 1993 (repr. 2001). Based on Horner (1963–64).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kelly 2005.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. Milindapañha.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Milindapanha, The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism

- ↑ Rhys Davids 1894, pp. xi-xiv.

- ↑ von Hinüber 2000, pp. 83-86, paragraph 173-179.

- ↑ According to Hinüber (2000), p. 83, para. 173, the first Chinese translation is believed to date from the 3rd century and is currently lost; a second Chinese translation, known as "Nagasena-bhiksu-sutra," (那先比丘經 Archived 2008-12-08 at the Wayback Machine.) dates from the 4th century. The extant second translation is "much shorter" than that of the current Pali-language Mil.

- ↑ von Hinüber 2000, pp. 85-86, paragraph 179.

- ↑ von Hinüber 2000, p. 83, paragraph 173.

- ↑ von Hinüber 2000, p. 83, paragraph 172.

- ↑ Rhys Davids 1894, p. xlvi.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Rhys Davids 1894, p. 374.

Sources

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University- Kelly, John (2005), Milindapañha: The Questions of King Milinda (excepts), Access to Insight

- von Hinüber, Oskar (2000), A Handbook of Pāli Literature, Berlin: de Gruyter, ISBN 9783110167382

- Rhys Davids, Thomas (1894), The questions of King Milinda, Part 2, The Clarendon press

External links

- ‘’The Questions of King Milinda’’ translated by Thomas William Rhys Davids.

- The Debate of King Milinda, Most Recent HTML and PDF Editions.

- The Debate of King Milinda, Abridged Edition by Bhikkhu Pesala

- Milindapañha – Selected passages in both Pali and English, translated by John Kelly

- Milinda Panha Sinhalese translation

| This article includes content from Milinda Panha on Wikipedia (view authors). License under CC BY-SA 3.0. |