Satipatthana

| Factors of Enlightenment |

|---|

|

Satipatthana (Pali: satipaṭṭhāna; S. smṛtyupasthāna; T. dran pa nye bar bzhag pa དྲན་པ་ཉེ་བར་བཞག་པ་; C. nianchu; J. nenjo) is translated as "establishments of mindfulness," "applications of mindfulness," "foundations of mindfulness," etc. It is a method for developing mindfulness (sati) through contemplating all aspects of experience. In this practice, the aspects of experience are divided into the following four domains:

- the physical body

- feelings/sensations (vedana)

- mind/mental states

- dhammas (frameworks for further contemplation)

Due to the common approach of focusing on four domains of experience, this meditative technique is often referred to as the "four establishments of mindfulness," etc.

Rupert Gethin states:

- Essentially what is assumed by the practice of the four ‘establishings of mindfulness’ is that one attains a certain degree of mental clarity and calm and then turns one’s attention first of all to watching various kinds of physical phenomena and activities, then to watching feeling as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral, then to watching one’s general mental state; and finally, at the fourth stage, to integrating the previous three stages so that finally one watches the totality of physical and mental processes.[1]

The four satipaṭṭhāna are identified as the first four factors of the thirty-seven factors of enlightenment.

Cultivation of mindfulness

Bhikkhu Bodhi states:

- The practice of Satipatthana meditation centers on the methodical cultivation of one simple mental faculty readily available to all of us at any moment. This is the faculty of mindfulness (sati), the capacity for attending to the content of our experience as it becomes manifest in the immediate present. What the Buddha shows in [the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta] is the tremendous, but generally hidden, power inherent in this simple mental function, a power that can unfold all the mind's potentials culminating in final deliverance from suffering.

- To exercise this power, however, mindfulness must be systematically cultivated, and [the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta] shows exactly how this is to be done. The key to the practice is to combine energy, mindfulness, and clear comprehension in attending to the phenomena of mind and body summed up in the "four arousings of mindfulness": body, feelings, consciousness, and mental objects. Most contemporary meditation teachers explain Satipatthana meditation as a means for generating insight (vipassana). While this is certainly a valid claim, we should also recognize that satipatthana meditation also generates concentration (samadhi). Unlike the forms of meditation which cultivate concentration and insight sequentially, Satipatthana brings both these faculties into being together, though naturally, in the actual process of development, concentration will have to gain a certain degree of stability before insight can exercise its penetrating function. In Satipatthana, the act of attending to each occasion of experience as it occurs in the moment fixes the mind firmly on the object. The continuous attention to the object, even when the object itself is constantly changing, stabilizes the mind in concentration, while the observation of the object in terms of its qualities and characteristics brings into being the insight knowledges.[2]

General aspects of the four satipaṭṭhāna

The following sections on the general aspects of the four satipaṭṭhāna are excerpted from Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization by Bhikkhu Anālayo.[3]

Survey of the four satipaṭṭhāna

Bhikkhu Anālayo states:

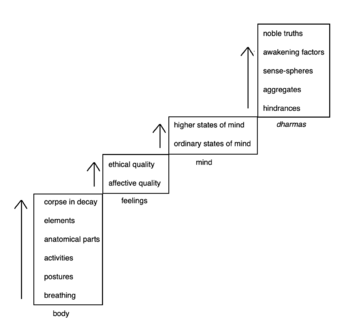

- The sequence of the contemplations listed in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta reveals a progressive pattern (see Fig. 1). Contemplation of the body progresses from the rudimentary experience of bodily postures and activities to contemplating the body’s anatomy. The increased sensitivity developed in this way forms the basis for contemplation of feelings, a shift of awareness from the immediately accessible physical aspects of experience to feelings as more refined and subtle objects of awareness.

- Contemplation of feeling divides feelings not only according to their affective quality into pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral types, but also distinguishes these according to their worldly or unworldly nature. The latter part of contemplation of feelings thus introduces an ethical distinction of feelings, which serves as a stepping-stone for directing awareness to the ethical distinction between wholesome and unwholesome states of mind, mentioned at the start of the next satipaṭṭhāna, contemplation of the mind.

- Contemplation of the mind proceeds from the presence or absence of four unwholesome states of mind (raga, dosa, moha, and distraction), to contemplating the presence or absence of four higher states of mind. The concern with higher states of mind in the latter part of the contemplation of the mind naturally lends itself to a detailed investigation of those factors which particularly obstruct deeper levels of concentration. These are the hindrances, the first object of contemplation of dhammas.

- After covering the hindrances to meditation practice, contemplation of dhammas progresses to two analyses of subjective experience: the five aggregates and the six sense-spheres. These analyses are followed by the awakening factors, the next contemplation of dhammas.

- The culmination of satipaṭṭhāna practice is reached with the contemplation of the four noble truths, full understanding of which coincides with realization.

- Considered in this way, the sequence of the satipaṭṭhāna contemplations leads progressively from grosser to more subtle levels. This linear progression is not without practical relevance, since the body contemplations recommend themselves as a foundational exercise for building up a basis of sati, while the final contemplation of the four noble truths covers the experience of Nibbāna (the third noble truth concerning the cessation of dukkha) and thus corresponds to the culmination of any successful implementation of satipaṭṭhāna.

- At the same time, however, this progressive pattern does not prescribe the only possible way of practising satipaṭṭhāna. To take the progression of the meditation exercises in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta as indicating a necessary sequence would severely limit the range of one’s practice, since only those experiences or phenomena that fit into this preconceived pattern would be proper objects of awareness. Yet a central characteristic of satipaṭṭhāna is awareness of phenomena as they are, and as they occur. Although such awareness will naturally proceed from the gross to the subtle, in actual practice it will quite probably vary from the sequence depicted in the discourse.

- A flexible and comprehensive development of satipaṭṭhāna should encompass all aspects of experience, in whatever sequence they occur. All satipaṭṭhānas can be of continual relevance throughout one’s progress along the path. The practice of contemplating the body, for example, is not something to be left behind and discarded at some more advanced point in one’s progress. Much rather, it continues to be a relevant practice even for an arahant. Understood in this way, the meditation exercises listed in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta can be seen as mutually supportive. The sequence in which they are practised may be altered in order to meet the needs of each individual meditator.

- Not only do the four satipaṭṭhānas support each other, but they could even be integrated within a single meditation practice. This is documented in the Ānāpānasati Sutta, which describes how mindfulness of breathing can be developed in such a way that it encompasses all four satipaṭṭhānas. This exposition demonstrates the possibility of comprehensively combining all four satipaṭṭhānas within the practice of a single meditation.[4]

The relevance of each satipaṭṭhāna for realization

Bhikkhu Anālayo states:

- According to the Ānāpānasati Sutta, it is possible to develop a variety of different aspects of satipaṭṭhāna contemplation with a single meditation object and in due course cover all four satipaṭṭhānas. This raises the question how far a single satipaṭṭhāna, or even a single meditation exercise, can be taken as a complete practice in its own right.

- Several discourses relate the practice of a single satipaṭṭhāna directly to realization. Similarly, the commentaries assign to each single satipaṭṭhāna meditation the capacity to lead to full awakening. This may well be why a high percentage of present-day meditation teachers focus on the use of a single meditation technique, on the ground that a single-minded and thorough perfection of one meditation technique can cover all aspects of satipaṭṭhāna, and thus be sufficient to gain realization.

- Indeed, the development of awareness with any particular meditation technique will automatically result in a marked increase in one’s general level of awareness, thereby enhancing one’s capacity to be mindful in regard to situations that do not form part of one’s primary object of meditation. In this way, even those aspects of satipaṭṭhāna that have not deliberately been made the object of contemplation to some extent still receive mindful attention as a by-product of the primary practice. Yet the exposition in the Ānāpānasati Sutta does not necessarily imply that by being aware of the breath one automatically covers all aspects of satipaṭṭhāna. What the Buddha demonstrated here was how a thorough development of sati can lead from the breath to a broad range of objects, encompassing different aspects of subjective reality. Clearly, such a broad range of aspects was the outcome of a deliberate development, otherwise the Buddha would not have needed to deliver a whole discourse on how to achieve this.

- In fact, several meditation teachers and scholars place a strong emphasis on covering all four satipaṭṭhānas in one’s practice. According to them, although one particular meditation practice can serve as the primary object of attention, the other aspects of satipaṭṭhāna should be deliberately contemplated too, even if only in a secondary manner. This approach can claim some support from the concluding part of the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, the “prediction” of realization. This passage stipulates the development of all four satipaṭṭhānas for contemplation to lead to the realization of the higher two stages of awakening: non-returning and arahantship. The fact that all four satipaṭṭhānas are mentioned suggests that it is the comprehensive practice of all four which is particularly capable of leading to high levels of realization. The same is also indicated by a statement in the Satipaṭṭhāna Saṃyutta, which relates the realization of arahantship to “complete” practice of the four satipaṭṭhānas, while partial practice corresponds to lesser levels of realization.

- In a passage in the Ānāpāna Saṃyutta, the Buddha compared the four satipaṭṭhānas to chariots coming from four directions, each driving through and thereby scattering a heap of dust lying at the centre of a crossroads.20 This simile suggests that each satipaṭṭhāna is in itself capable of overcoming unwholesome states, just as any of the chariots is able to scatter the heap of dust. At the same time this simile also illustrates the cooperative effect of all four satipaṭṭhānas, since, with chariots coming from all directions, the heap of dust will be scattered even more.

- Thus any single meditation practice from the satipaṭṭhāna scheme is capable of leading to deep insight, especially if developed according to the key instructions given in the “definition” and “refrain” of the discourse. Nevertheless, an attempt to cover all four satipaṭṭhānas in one’s practice does more justice to the distinct character of the various meditations described in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta and thereby ensures speedy progress and a balanced and comprehensive development.[4]

The character of each satipaṭṭhāna

| body | feelings | mind | dhammas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aggregate | material form | feeling | consciousness | cognition + volition |

| character | slow craver | quick craver | slow theorizer | quick theorizer |

| insight | absence of beauty | unsatisfactoriness | impermanence | absence of self |

Bhikkhu Analayo states:

- Each satipaṭṭhāna has a different character and can thereby serve a slightly different purpose. This is documented in the Nettippakaraṇa and the commentaries, which illustrate the particular character of each satipaṭṭhāna with a set of correlations (see table).

- According to the commentaries, each of the four satipaṭṭhānas corresponds to a particular aggregate: the aggregates of material form (rūpa), feeling (vedanā), and consciousness (viññāṇa) match the first three satipaṭṭhānas, while the aggregates of cognition (saññā) and volitions (saṅkhārā) correspond to the contemplation of dhammas.

- On closer inspection, this correlation appears a little forced, since the third satipaṭṭhāna, contemplation of the mind, corresponds to all mental aggregates and not only to consciousness. Moreover, the fourth satipaṭṭhāna, contemplation of dhammas, includes the entire set of the five aggregates as one of its meditations, and thus has a wider range than just the two aggregates of cognition (saññā) and volition (saṅkhārā).

- Nevertheless, what the commentaries might intend to indicate is that all aspects of one’s subjective experience are to be investigated with the aid of the four satipaṭṭhānas. Understood in this way, the division into four satipaṭṭhānas represents an analytical approach similar to a division of subjective experience into the five aggregates. Both attempt to dissolve the illusion of the observer’s substantiality. By turning awareness to different facets of one’s subjective experience, these aspects will be experienced simply as objects, and the notion of compactness, the sense of a solid “I”, will begin to disintegrate. In this way, the more subjective experience can be seen “objectively”, the more the “I”-dentification diminishes. This correlates well with the Buddha’s instruction to investigate thoroughly each aggregate to the point where no more “I” can be found.

- In addition to the aggregate correlation, the commentaries recommend each of the four satipaṭṭhānas for a specific type of character or inclination. According to them, body and feeling contemplation should be the main field of practice for those who tend towards craving, while meditators given to intellectual speculation should place more emphasis on contemplating mind or dhammas. Understood in this way, practice of the first two satipaṭṭhānas suits those with a more affective inclination, while the last two are recommended for those of a more cognitive orientation. In both cases, those whose character is to think and react quickly can profitably centre their practice on the relatively subtler contemplations of feelings or dhammas, while those whose mental faculties are more circumspect and measured will have better results if they base their practice on the grosser objects of body or mind. Although these recommendations are expressed in terms of character type, they could also be applied to one’s momentary disposition: one could choose that satipaṭṭhāna that best corresponds to one’s state of mind, so that when one feels sluggish and desirous, for example, contemplation of the body would be the appropriate practice to be undertaken.

- “The Nettippakaraṇa and the Visuddhimagga also set the four satipaṭṭhānas in opposition to the four distortions (vipallāsas), which are to “mistake” what is unattractive, unsatisfactory, impermanent, and not-self, for being attractive, satisfactory, permanent, and a self. According to them, contemplation of the body has the potential to reveal in particular the absence of bodily beauty; observation of the true nature of feelings can counter one’s incessant search for fleeting pleasures; awareness of the ceaseless succession of states of mind can disclose the impermanent nature of all subjective experience; and contemplation of dhammas can reveal that the notion of a “substantial and permanent self is nothing but an illusion. This presentation brings to light the main theme that underlies each of the four satipaṭṭhānas and indicates which of them is particularly appropriate for dispelling the illusion of beauty, happiness, permanence, or self. Although the corresponding insights are certainly not restricted to one satipaṭṭhāna alone, nevertheless this particular correlation indicates which satipaṭṭhāna is particularly suitable in order to correct a specific distortion (vipallāsa). This correlation, too, may be fruitfully applied in accordance with one’s general character disposition, or else can be used in order to counteract the momentary manifestation of any particular distortion.[4]

Etymology of the term satipaṭṭhāna

Bhikkhu Anālayo states:

- The term satipaṭṭhāna can be explained as a compound of sati, “mindfulness” or “awareness”, and upaṭṭhāna, with the u of the latter term dropped by vowel elision. The Pāli term upaṭṭhāna literally means “placing near”, and in the present context refers to a particular way of “being present” and “attending” to something with mindfulness. In the discourses, the corresponding verb upaṭṭhahati often denotes various nuances of “being present”, or else “attending”. Understood in this way, “satipaṭṭhāna” means that sati “stands by”, in the sense of being present; sati is “ready at hand”, in the sense of attending to the current situation. Satipaṭṭhāna can then be translated as “presence of mindfulness” or as “attending with mindfulness”.

- The commentaries, however, derive satipaṭṭhāna from the word “foundation” or “cause” (paṭṭhāna). This seems unlikely, since in the discourses contained in the Pāli canon the corresponding verb paṭṭhahati never occurs together with sati. Moreover, the noun paṭṭhāna is not found at all in the early discourses, but comes into use only in the historically later Abhidhamma and the commentaries. In contrast, the discourses frequently relate sati to the verb upaṭṭhahati, indicating that “presence” (upaṭṭhāna) is the etymologically correct derivation. In fact, the equivalent Sanskrit term is smṛtyupasthāna, which shows that upasthāna, or its Pāli equivalent upaṭṭhāna, is the correct choice for the compound.[4]

The meaning of dhammas within "mindfulness of dhammas"

The Pali term dhamma can assumme a variety of meanings, depending upon the context in which it is used.[5]

In the context of the four satipatthāna, the term dhamma is often translated as "mental objects." However, Bhikkhu Analayo suggests that translating dhamma as "mental object" in this context is problematic for multiple reasons. The three prior satipatthāna (body, sensations, mind) can become mental objects in themselves, and those objects, such as the hindrances, aggregates and sense bases, identified under the term dhamma are far from an exhaustive list of all possible mental objects.[5]

Bhikkhu Analayo states:

- What this satipaṭṭhāna is actually concerned with are specific mental qualities (such as the five hindrances and the seven awakening factors), and analyses of experience into specific categories (such as the five aggregates, the six sense-spheres, and the four noble truths). These mental factors and categories constitute central aspects of the Buddha’s way of teaching, the Dhamma.2 These classificatory schemes are not in themselves the objects of meditation, but constitute frameworks or points of reference to be applied during contemplation. During actual practice one is to look at whatever is experienced in terms of these dhammas.3 Thus the dhammas mentioned in this satipaṭṭhāna are not “mental objects”, but are applied to whatever becomes an object of the mind or of any other sense door during contemplation.[5]

Bhikkhu Analayo also cites Thomas Gyori as stating that contemplation of these dhammā "are specifically intended to invest the mind with a soteriological orientation."[6][7] He further cites Richard Gombrich as writing that contemplating these dhammā teaches one "to see the world through Buddhist spectacles."[8][9]

Hence, the term dhammā in this context can be understood as "frameworks or points of reference to be applied during contemplation." And these frameworks are understood as orienting one towards liberation (nirvana) in the Buddhist sense.

Traditional textual sources

In the Pāli tradition, the main texts for studying the satipatthana are the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta and the Mahasatipatthana Sutta (an expanded version of the Satipatthana Sutta). These texts are also important sources for contemporary teachers of all traditions.

The satipaṭṭhāna are also presented in the great Abhidharma commentary of the Pali tradition, the the Visuddhimagga. Many texts of the Samyutta Nikaya of the Pali Canon also refer to the satipaṭṭhāna.

Within the Sanskrit tradition, the Chinese Canon contains two parallels to the Satipatthana Sutta; Madhyama Āgama No. 26 and Ekottara Agama 12.1. The satipaṭṭhāna are also treated in major Abhidharma commentaries such as the Abhidharmakosha and the Yogacarabhumi-sastra. In the Tibetan tradition, the satipaṭṭhāna are mainly known through the Abhidharmakosha and other commentaries.

See also

References

- ↑ Gethin 1998, s.v. Chapter 7.

- ↑ Bhikkhu Bodhi,

The Way of Mindfulness, Access to Insight

The Way of Mindfulness, Access to Insight

- ↑ Bhikkhu Anālayo 2003.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Bhikkhu Anālayo 2003, Chapter I: General Aspects of the Direct Path.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bhikkhu Anālayo 2003, Chapter IX: The Hindrances.

- ↑ Gyori 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ Bhikkhu Anālayo 2003, Chapter IX: The Hindrances, nn. 2.

- ↑ Gombrich 1996, p. 36.

- ↑ Bhikkhu Anālayo 2003, Chapter IX: The Hindrances, nn 3.

Sources

- Bhikkhu Anālayo (2003), Satipaṭṭhāna : The Direct Path to Realization, Birmingham: Windhorse, ISBN 1-899579-54-0

- Bhikkhu Bodhi,

The Way of Mindfulness, Access to Insight

The Way of Mindfulness, Access to Insight  Gethin, Rupert (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press

Gethin, Rupert (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press- Gombrich, Richard F. (1996), How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings, Athlone Press, ISBN 0-415-37123-6.

- Gyori, Thomas I (1996), The Foundations of Mindfulness (Satipatthāna) as a Microcosm of the Theravāda Buddhist World View (M.A. dissertation), Washington: American University

Further reading

- Anālayo (2006). Satipatthāna: The Direct Path to Realization. Birmingham: Windhorse Publications. ISBN 1-899579-54-0

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (2000). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-168-8.

- Gunaratana (2012). The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English. Boston: Wisdom Pub. ISBN 978-1-61429-038-4.

- Nanamoli, Bhikkhu and Bhikkhu Bodhi (trans.) (1995), The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Somerville: Wisdom Pubs ISBN 0-86171-072-X.

- Thich Nhat Hanh (trans. Annabel Laity) (2005). Transformation and Healing : Sutra on the Four Establishments of Mindfulness . Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press. ISBN 0-938077-34-1.

- Nyanasatta Thera (2004). Satipatthana Sutta: The Foundations of Mindfulness (MN 10). Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.010.nysa.html.

- Nyanaponika Thera (1954). The Heart of Buddhist Meditation.

- Olendzki, Andrew (2005). Makkata Sutta: The Foolish Monkey (SN 47.7). Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn47/sn47.007.olen.html.

- Silananda (2002). The Four Foundations of Mindfulness. Boston: Wisdom Pub. ISBN 0-86171-328-1.

- Soma Thera (1941; 6th ed. 2003). The Way of Mindfulness. Kandy: BPS. ISBN 955-24-0256-5. Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/soma/wayof.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997). Sakunagghi Sutta (The Hawk) (SN 47.6). Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn47/sn47.006.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997a). Sedaka Sutta: At Sedaka (The Acrobat) (SN 47.19). Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn47/sn47.019.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997b). Sedaka Sutta: At Sedaka (The Beauty Queen) (SN 47.20). Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn47/sn47.020.than.html.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2008). Satipatthana Sutta: Frames of Reference (MN 10). Available at http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.010.than.html.

External links

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Agendas of Mindfulness, Dhammatalks.org

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Agendas of Mindfulness, Dhammatalks.org- The Four Foundations of Mindfulness - from the Satipatthana Sutta: D.22

- Satipatthana (Wikipedia)