|

ENERGY

|

GAIN ENERGY

APPRENTICE

LEVEL1

|

THE

ENERGY BLOCKAGE REMOVAL

PROCESS

|

THE

KARMA CLEARING

PROCESS

APPRENTICE

LEVEL3

|

MASTERY

OF RELATIONSHIPS

TANTRA

APPRENTICE

LEVEL4

|

2005 AND 2006

|

| [Previous] | [Next] | |

INTRODUCTION |

HATHA YOGA is a discipline involving various bodily and mental controls,[1]

[1] The traditional meaning of the word Hatha is: (1) violence, force; (2) oppression, rapine; it is used adverbially in the sense of forcibly, violently, suddenly, against ones will; hence this form of Yoga is sometimes called forced Yoga.

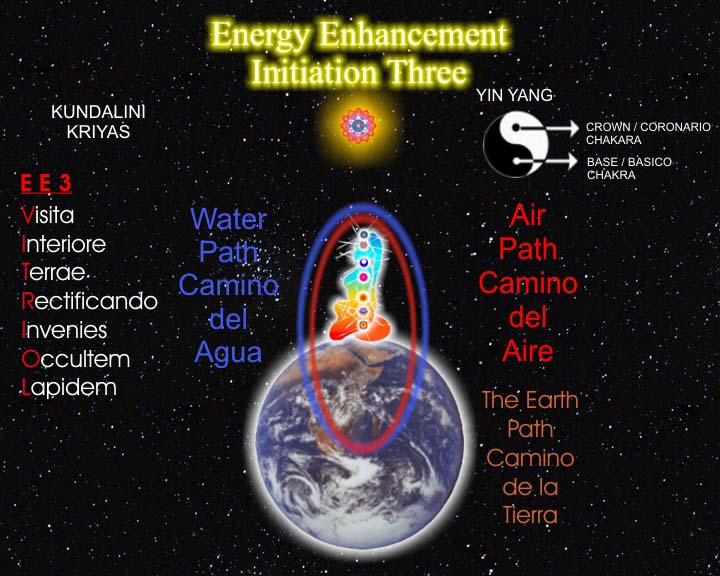

but central to them all is the regulation of the breath. Hatha is derived from two roots, ha (sun) and tha (moon), which symbolically refer to the flowing of breath in the right nostril, called the sun breath, and the flowing of breath in the left nostril, called the moon breath. Yoga is derived from the root yuj (to join); therefore, Hatha Yoga is the uniting of these two breaths. The effect is believed to induce a mental condition called samãdhi. This is not an imaginary or mythical state, though it is explained by myths, but is an actual condition that can be subjectively experienced and objectively observed.

In order to bring about a stabilization of the breath, considerable emphasis is placed upon purification of the body and the use of various physical techniques. The training of the physical body as an end in itself is called Ghatastha Yoga. It is maintained that the methods employed do not violate any of the physical laws of the body; so they have been given the name Physiological Yoga. The practices are said to make dynamic a latent force in the body called Kunda1inî; hence the term Kunda1inî Yoga is frequently employed. All processes utilized are directed toward the single aim of stilling the mind. For this condition the method applied is known as Laya Yoga. The complete subjugation of the mind is considered to be the Royal Road and is called Rãja Yoga. All these forms are often classified under the general heading Tãntrik Yoga, since they represent the practical discipline based on tãntrik philosophy;[2]

[2] See the works of Sir John Woodroffe, who also wrote under the pseudonym Arthur Avalon: The Serpent Power, Shakti and Shakta, Garland of Letters, The Great Liberation, and Principles of Tantra (in two volumes). The chief classic texts are now available in English. Among the important earlier treatments of our subject should be mentioned Omans The Mystics, Ascetics, and Saints of India, and Schmidts Fakire und Fakirtum in alten und modernen Indien. Schmidts work is based largely on Omans but contains a German translation of the Gheranda Samhită and a valuable series of illustrations collected in India by Garbe in 1886. The more recent works and editions are noted in the Bibliography. The two volumes by Kuva1ay~nanda contain illustrations of most of the postures.

but tantra is used loosely for a variety of systems, chiefly for the purpose of distinguishing them from other forms of non-physiological discipline. These other forms of Yoga offer intellectual and devotional processes for subduing the mind and producing tranquillity, but do not prescribe any system of physiological or bodily discipline.[3]

[3] The generally accepted forms of Yoga are discussed in Siva Samhită, v, 9: "The Yoga is of four kinds:- First Mantra-Yoga, second Hatha-Yoga, third Laya-Yoga, fourth Răja-Yoga, which discards duality." Evans-Wentz, in Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines, p. 33, says: "The various aspects or parts of Yoga and their general relationship to one another may now be set forth concisely by the following table:

|

THE PART |

GIVING MASTERY OF |

LEADING TO YOGIC CONTROL OF |

| I. Hatha Yoga | breath | physical body and vitality |

| II. Laya Yoga | will | powers of mind |

| (1) Bhakti Yoga | love | powers of divine love |

| (2) Shakti Yoga | energy | energizing forces of Nature |

| (3) Mantra Yoga | sound | powers of sound vibration |

| (4) Yantra Yoga | form | powers of geometrical form |

| III. Dhyăna Yoga | thought | powers of thought-processes |

| IV. Răja Yoga | method | powers of discrimination |

| (1) Jńana Yoga | knowledge | powers of intellect |

| (2) Karma Yoga | activity | powers of action |

| (3) Kundalinî Yoga | Kundalinî | powers of psychic nerve force |

| (4) Samădhi Yoga | self |

The power of ecstasy |

The techniques of Hatha Yoga are given in the classic texts: Hatha Yoga Pradîpikã, Gheranda Samhitã, and Siva Samhitã. These are the leading treatises on the subject. The first is considered to be the standard authority, and in many instances the verses of the second correspond closely. The third presents a fuller account and introduces a brief outline of the general attitude toward Hatha Yoga, showing its importance and metaphysical foundation.(4)

[4] Siva Samhită, i, 1-19, opens with the following discussion, "The Jnăna [Gnosis] alone is eternal; it is without beginning or end; there exists no other real substance. Diversities which we see in the world are results of senseconditions; when the latter cease, then this Jnăna alone, and nothing else, remains. I, Ivara, the lover of my devotees, and Giver of spiritual emancipation to all creatures, thus declare the science of Yogănuăsana (the exposition of Yoga). In it are discarded all those doctrines of disputants, which lead to false knowledge. It is for the spiritual disenthralment of persons whose minds are undistracted and fully turned towards me.

"Some praise truth, others purification and asceticism; some praise forgiveness, others equality and sincerity. Some praise alms-giving, others laud sacrifices made in honour of ones ancestors; some praise action (Karma), others think dispassion (Vairăgya) to be the best. Some wise persons praise the performance of the duties of the householder; other authorities hold up fire-sacrifice, &c., as the highest. Some praise Mantra Yoga, others the frequenting of places of pilgrimage. Thus diverse are the ways which people declare for emancipation. Being thus diversely engaged in this world, even those who still know what actions are good and what evil, though free from sin, become subject to bewilderment. Persons who follow these doctrines, having committed good and bad actions, constantly wander in the worlds, in the cycle of births and deaths, bound by dire necessity. Others, wiser among the many, and eagerly devoted to the investigation of the occult, declare that the souls are many and eternal, and omnipresent. Others say, Only those things can be said to exist which are perceived through the senses and nothing besides them; where is heaven or hell? Such is their firm belief. Others believe the world to be a current of consciousness and no material entity; some call the void as the greatest. Others believe in two essences:Matter (Prakriti) and Spirit (Purusa). Thus believing in widely different doctrines, with faces turned away from the supreme goal, think, according to their understanding and education, that this universe is without God; others believe there is God, basing their assertions on various irrefutable arguments, founded on texts, declaring difference between soul and God, and anxious to establish the existence of God. These and many other sages with various different denominations, have been declared in the Săstras as leaders of the human mind into delusions. It is not possible to describe fully the doctrines of these persons so fond of quarrel and contention; people thus wander in this universe, being driven away from the path of emancipation.

"Having studied all the Săstras and having pondered over them well, again and again, this Yoga Săstras has been found to be the only true and firm doctrine. Since by Yoga all this verily is known as a certainty, all exertion should be made to acquire it. What is the necessity then of any other doctrines? This Yoga Săstras, now being declared by us, is a very secret doctrine, only to be revealed to a high souled pious devotee throughout the three worlds."

The other texts assume that the student is thoroughly familiar with these principles. None of them discuss Yoga, for they were meant to be outlines, and the details were supposed to be supplied by the teacher. Yoga was never intended to serve as a spiritual correspondence course, but was given as a method of self-culture to be practised under direct supervision. It was never intended that Yoga should be practised without the guidance of a teacher. It is just as impossible to do so as it is to become a finished musician from a mailorder course. The texts were meant only to serve as a guide; a teacher was to furnish the details necessary in each individual case. All the texts are couched in. the mysterious, or technical, phraseology of tãntrik literature which presents such a stumbling block for the western mind.

The texts agree that Hatha Yoga is the stepping stone and that ultimate liberation comes from the practice of Rãja Yoga. The Pradîpikã opens:

Salvation to Adinãtha (Siva) who expounded the knowledge of Hatha Yoga, which like a staircase leads the aspirant to the highpinnacled Rãja Yoga. Yogin Svãtmãrãma, after saluting his Guru rînãtha, explains Hatha Yoga solely for the attainment of Raja Yoga. Owing to the darkness arising from the multiplicity of opinions which spring from error people are unable to know the Raja Yoga. Compassionate Svãtmãrãma holds the Hatha Yoga Pradîpikã like a torch to dispel it.[5]

[5] Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 13. Compare Gheranda Samhită, opening verse, "I salute that Adîvara who taught first the science of Hatha Yogaa science that stands out as a ladder that leads to the higher heights of Raja Yoga."

Some of the most highly esteemed teachers of ancient India maintain that they have received enlightenment through the practices of Hatha Yoga and according to tradition passed the method down by word of mouth, from teacher to pupil, to the present day.

Matsyendra, Goraksa,[6]

[6] For the life and teachings see Briggs, Gorakhnăth and the Kănphata Yogis. See also Mitra, Yoga Văsishtha Mahărămăyana of Vălmîki, and Evans-Wentz, Tibets Great Yogi Milarepa.

etc., knew Hatha Vidyã and by their favour Yogin Svãtmãrãma also knows it. (The following Siddhas [masters] arc said to have existed in former times:) Sri Adinãtha (Siva), Matsyendra, Sãbara, Ananada, Bhairava, Chaurangî, Minanãtha, Goraksanãtha, Virûpãksa, Bileaya, Manthãna, Bhairava, Siddhi, Buddha, Kanthadi, Korantaka, Surãnanda, Siddhapãda, Charpati, Kãnerî, Pûjyanãda, Ni yanãtha, Niranjana, Kapãli, Vindunãtha, Kaka-Chandîvara, Allãma, Prabhudeva, Ghodã, Cholî, Tiniti, Bhãnukî, Nãradeva, Khanda, Kãpãlika. These and other Mahãsiddhas (great masters), through the potency of Hatha Yoga, breaking the sceptre of death, are roaming in the universe. Like a house protecting one from the heat of the sun, Hat Yoga shelters all suffering from Tapas; and, similarly, it is the supporting tortoise, as it were, for those who are constantly devoted to the practice of Yoga.[7]

[7] For biographical accounts of two other renowned Yogis see Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 4-10 Compare the opening discussion in Gheranda Samhită, i, 1-11: "Once Canda-Kăpăli went to the hermitage of Gheranda, saluted him with great reverence and devotion, and inquired of him, 0 Master of Yoga! 0 best of the Yogins! 0 Lord! I wish now to hear the physiological Yoga, which leads to the knowledge of truth (or Tattva-Jńana).

Well asked, indeed, 0 mighty armed! I shall tell thee, 0 child! what thou askest me. Attend to it with diligence. There are no fetters like those of Illusion (Măyă), no strength like that which comes from discipline (Yoga), there is no friend higher than knowledge (Jńana), and no greater enemy than Egoism (Ahamkăra). As by learning the alphabets one can, through practice, master all the sciences, so by thoroughly practising first the (physical) training, one acquires the Knowledge of the True. On account of good and bad deeds, the bodies of all animated beings are produced, and the bodies give rise to work (Karma which leads to rebirth) and thus the circle is continued like that of a rotating mill. As the rotating mill in drawing water from a well goes up and down, moved by the bullocks (filling and exhausting the buckets again and again), so the soul passes through life and death moved by its Deeds. Like unto an unbaked earthen pot thrown in water, the body is soon decayed (in this world). Bake it hard in the fire of Yoga in order to strengthen and purify the body.

"The seven exercises which appertain to this Yoga of the body are the following :- Purification, strengthening, steadying, calming, and those leading to lightness, perception, and isolationist The purification is acquired by the regular performance of six practices (purification processes); and. Asana or posture Drdhată or strength; 3rd Mudră gives Sthirată or steadiness; 4th Pratyăhăra gives Dhîrată or calmness; 5th Prănăyăma gives lightness or Laghiman; 6th Dhyăna gives perception (Pratyaksatva) of Self; and 7th Samădhi gives isolation (Nirliptată), which is verily the Freedom. "

Hatha Yoga is not taught indiscriminately to everyone, for it is believed that "a yogi, desirous of success, should keep the knowledge of Hatha Yoga secret; for

it becomes potent by concealing, and impotent by exposing."[8][8] Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 11.

In order to become worthy of the teachings, the student must first fulfil the moral requirements called the yamas and niyamas, which are the moral prerequisites to the study of Yoga.

The ten Yamas (rules of conduct) are: ahimsã (noninjuring), truth, non-stealing, continence, forgiveness, endurance, compassion, sincerity, sparing diet and cleanliness. The ten Niyamas (rules of inner control) mentioned by those proficient in the knowledge of Yoga are: Tapas (penance), contentment, belief in God, charity, adoration of God, hearing discourses on the principles of religion, modesty, intellect, meditation, and Yajña [sacrifice].[9]

[9] Ibid., 17-18. Requirements for different, forms of Yoga are discussed in Siva Samhită, v, 10-14:

"Know that aspirants are of four orders:-mild, moderate, ardent and the most ardent the best who can cross the ocean of the world.

"(Mild) entitled to Mantra-Yoga. Men of small enterprise, oblivious, sickly and finding faults with their teachers; avaricious sinful gourmands, and attached helplessly to their wives; fickle, timid, diseased, not independent, and cruel; those whose characters are bad and who are weak know all the above to be mild sădhaks. With great efforts such men succeed in twelve years; them the teacher should know fit for the Mantra-Yoga.

"(Moderate) entitled to Laya-Yoga. Liberal minded, merciful, desirous of virtue, sweet in their speech; who never go to extremes in any undertaking these are the middling. These are to be initiated by the teacher in Laya-Yoga.

"(Ardent) entitled to Hatha Yoga. Steady-minded, knowing the Laya-Yoga, independent, full of energy, magnanimous, full of sympathy, forgiving, truthful, courageous, full of faith, worshippers of the lotus-feet of their Gurus, engaged always in the practice of Yoga know such men to be adhimătra. They obtain success in the practice of Yoga within six years, and ought to be initiated in Hatha-Yoga and its branches.

"(The most ardent) entitled to all Yogas. Those who have the largest amount of energy, are enterprising, engaging, heroic, who know the Săstras, and are persevering, free from the effects of blind emotions, and, not easily confused, who are in the prime of their youth, moderate in their diet, rulers of their senses, fearless, clean, skilful, charitable, a help to all; competent, firm, talented, contented, forgiving, good natured, religious, who keep their endeavours secret, of sweet speech, peaceful, who have faith in scriptures and are worshippers of God and Guru, who are averse to fritter away their time in society, and are free from any grievous malady, who are acquainted with the duties of the adhimătra, and are the practitioners of every kind of Yoga undoubtedly, they obtain success in three years; they are entitled to be initiated in all kinds of Yoga, without any hesitation. "

The text goes a step further and outlines the forms of conduct that hinder one's progress and those that enable him to succeed.

Yoga is destroyed by the following six causes:- Overeating, exertion, talkativeness, adhering to rules (i.e. cold bath in the morning, eating at night, eating fruits only), company of men, and unsteadiness. The following six bring speedy success in Yoga:- courage, daring, perseverance, discriminative knowledge, faith, aloofness from company.[10]

[10] Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 15-16. Compare the discussion of obstacles given in Siva Samhită, v, 1-8: "Părvatî said, 0 Lord, 0 beloved Sankara! tell me, for the sake of those whose minds search after the supreme end, the obstacles and the hindrances to Yoga. Siva said, Hear, 0 Goddess! I shall tell thee all the obstacles that stand in the path of Yoga. For the attainment of emancipation enjoyments (Bhoga) are the greatest of all impediments.

"BHOGA (enjoyment). Women, beds, seats, dresses, and riches are obstacles to Yoga. Betels, dainty dishes, carriages, kingdoms, lordliness and powers; gold, silver, as well as copper, gems, aloe wood, and kine; learning the Vedas and the Săstras; dancing, singing and ornaments; harp, flute and drum; riding on elephants and horses; wives and children, worldly enjoyments; all these are so many impediments. These are the obstacles which arise from bhoga (enjoyment). Hear now the impediments which arise from ritualistic religion.

"DHARMA (Ritualism of Religion). The following are the obstacles which dharma interposes: ablutions, worship of deities, observing the sacred days of the moon, fire, sacrifice, hankering after Moksa, vows and penances, fasts, religious observances, silence, the ascetic practices, contemplation and the object of contemplation, Mantras, and alms-giving, worldwide fame, excavating and endowing of tanks, wells, ponds, convents and groves; sacrifices, vows of starvation, Chăndrăyana, and pilgrimages.

"JNANA (Knowledge-obstacles). Now I shall describe, 0 Părvati, the obstacles which arise from knowledge. Sitting in the Gomukha posture and practising Dhauti (washing the intestines by Hatha Yoga). Knowledge of the distribution of the nădis (the vessels of the human body), learning of pratyăhăra (subjugation of senses), trying to awaken the Kundalinî force, by moving quickly the belly (a process of Hatha Yoga), entering into the path of the Indriyas, and knowledge of the action of the Nădis; these are the obstacles. Now listen to the mistaken notions of diet, 0! Părvati.

"That Samădhi (trance) can be at once induced by drinking certain new chemical essences and by eating certain kinds of food, is a mistake. Now hear about the mistaken notion of the influence of company.

"Keeping the company of the virtuous, and avoiding that of the vicious (is a mistaken notion). Measuring of the heaviness and lightness of the inspired and expired air (is an erroneous idea).

"Brahman is in the body or He is the maker of form, or He has a form, or He has no form, or He is everythingall these consoling doctrines are obstacles. Such notions are impediments in the shape of Jńana (Knowledge). "

These general restrictions and recommendations apply to all forms of Yoga.

Yoga is defined as "the restraint of mental modifications".[11]

[11] The Yoga Sutras of Patańjali, i, 2. Patańjali is considered to be the Father of Yoga, for it is believed that he first recorded systematically the practices.

For this the primary pre-requisite is posture, since without

it peace of mind is impossible. Every bodily movement, twitch, or strain, every nerve impulse, as well as the flow of the breath, causes restlessness. Patañjali points out the necessity of posture, called ãsana in Sanskrit, but he does not specify any particular form, for this is a matter to be settled according to the needs of each individual.[12][12] The posture does not necessarily have to be a sitting one, for some are standing upright, lying down, bending or standing on the head. See also Gheranda Samhită, ii, 36, "Stand straight on one leg (the left), bending the right leg, and placing the right foot on the root of the left thigh; standing thus like a tree on the ground, is called the [Vrksăsana] tree posture"; see illustration.

Ibid., 19: "Lying flat on the ground (on ones back) like a corpse is called the Mrtăsana (Corpse-posture). This posture destroys fatigue, and quiets the agitation of the mind." This posture is sometimes called savăsana. Compare Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 34: "Lying down on the ground like a corpse, is called Savăsana. It removes fatigue and gives rest to the mind." In padhahasthăsana the Yogi stands and touches his feet with his hands (see illustration).

In vămadaksinapadăsana the legs are brought up to right angles with the body, a kind of goose step. Other postures will be described further on.

Any ãsana that is steady and pleasant is considered suitable. Vãchaspati says ãsana means any position that may secure ease.[13]

[13] The Yoga Sutras of Patańjali, ii, 46. Văchaspati is a famous commentator on the Yoga Sutras of Patańjali.

In the famous tãntrik treatise on Hatha Yoga, known as Hatha Yoga Pradîpikã, which I have used as the basis of this comparative treatment, opens its section on ãsanas as follows: "Being the first accessory of Hatha Yoga, ãsana is discussed first. It should be practised for gaining steady posture, health and lightness of body.[14]

[14] Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 19.

Without further comment the text describes the fifteen most important ãsanas adopted by such great Yogis as Vaistha and Matsyendra. The list is as follows: Svastikãsana, Gomukhãsana, Vîrãsana, Kurmãsana, Kukkutãsana, Uttãnakurmakãsana, Dhanurãsana, Matsyãsana, Pascimottãnãsana, Mayurãsana, avãsana, Siddhãsana, Padmãsana, Simhãsana, and Bhadrãsana.[15]

[15] Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 21-57. The text points out that they are not all necessary. See 35-6: "iva taught eighty-four ăsanas. Of these the first four being essential ones, I am going to explain them here. These four are: Siddha, Padma, Simha, and Bhadra. Even of these, the Siddhăsana being very comfortable, one should always practise it." Siddhăsana and padmăsana will be discussed more fully elsewhere. Simhăsana is described in the text, i, 52-4: "Press the heels on both sides of the seam of the scrotum in such a way that the left heel touches the right side and the right heel touches the left side of it. Place the hands on the knees, with stretched fingers, and keeping the mouth open and the mind collected, gaze on the tip of the nose. This is Simhăsana, held secret by the best of Yogis. This excellent ăsana effects the completion of the three Bandhas. (Műlabandha, Kantha or Jălandhara Bandha and Uddiyăna Bandha)."

Compare Gheranda Samhită, ii, 14-15: "The two heels to be placed under the scrotum contrariwise (i.e., left heel on the right side and the right heel on the left side of it) and turned upwards, the knees to be placed on the ground, and the hands placed on the knees, mouth to be kept open; practising the Jălandhara mudră one should fix his gaze on the tip of the nose. This is the Simhăsana (Lion posture), the destroyer of all diseases."

For Bhadrăsana see Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 55-7: "Place the heels on either side of the seam of the scrotum, keeping the left heel on the left side and the right one on the right side, hold the feet firmly joined to one another with both the hands. This Bhadrăsana is the destroyer of all the diseases. The expert Yogis calls this Gorakăsana. By sitting with this ăsana, the Yogi gets rid of fatigue."

Compare Gheranda Samhită, ii, 9-10: "Place the heels crosswise under the testes attentively; cross the hands behind the back and take hold of the toes of the feet. Fix the gaze on the tip of the nose, having previous adopted the Mudră called jălandhara. This is the Bhadrăsana (or happy posture) which destroys all sorts of disease." A different posture is described for Goraksăsana in Gheranda Samhită, ii, 24-5: "Between the knees and the thighs, the two feet turned upward and placed in a hidden way, the heels being carefully covered by the two hands outstretched; the throat being contracted, let one fix the gaze on the tip of the nose. This is called Gorakăsana. It gives success to the Yogins."

The Gheranda Samhitã, a tãntrik work on Hatha Yoga, says:

There are eighty-four hundreds of thousands of Asanas described by Siva. The postures are as many in number as there are number of living creatures in this universe. Among them eighty-four are the best; and among these eighty-four, thirty-two have been found useful for mankind in this world. The thirty-two Asanas that give perfection in this mortal world are the following: Siddhãsana (Perfect posture); Padmãsana (Lotus posture); Bhadrãsana (Gentle posture); Muktãsana (Free posture); Vajrãsana (Thunderbolt posture); Svastikãsana (Prosperous posture); Simhãsana (Lion posture); Gomukhãsana (Cowmouth posture); Vîrãsana (Heroic posture); Dhanurãsana (Bow posture); Mrtãsana (Corpse posture); Guptãsana (Hidden posture); Mãtsyãsana (Fish posture); Matsyendrãsana; Gorakãsana; Pascimottãnãsana; Utkatãsana (Hazardous posture); Samkatãsana (Dangerous posture); Mayûrãsana (Peacock posture); Kukkutãsana (Cock posture); Kûrmãsana (Tortoise posture); Uttãna Kûrmakãsana; Uttãna Mandukãsana; Vrksãsana (Tree posture); Mandukãsana (Frog posture); Garudãsana (Eagle posture); Vrsãsana (Bull posture); Salabhãsana (Locust posture); Makarãsana (Dolphin posture); Ustrãsana (Camel posture); Bhujañgãsana (Cobra posture); Yogãsana.[16]

[16] Gheranda Samhită, ii, 1-6. Compare Siva Samhită, iii, 84: "There are eighty-four postures of various modes. Out of them, four ought to be adopted, which I mention below:- i. Siddhăsana; a. Padmăsana; 3. Ugrăsana [Pascimottănăsana]; 4. Svastikăsana." All but the last of these postures will be given later.

Svastikăsana is described, iii, 95-7: "Place the soles of the feet completely under the thighs, keep the body straight and sit at ease. This is called the Svastikăsana. In this way the wise Yogi should practise the regulation of the air. No disease can attack his body, and he obtains Văyu Siddhi. This is also called the Sukhăsana (the easy posture). This health-giving, good Svastikăsana should be kept secret by the Yogi."

Compare Gheranda Samhită, ii, 13: "Drawing the legs and thighs together and placing the feet between them, keeping the body in its easy condition and sitting straight, constitute the posture called the Svastikăsana."

Compare Hatha Yoga Pradîpikă, i, 21, "Having kept both the feet between the knees and the thighs, with body straight, when one sits calmly, it is called Svastikăsana."

In this literature many fantastic claims are made, and mystic panaceas are promised for each of the ãsanas and other disciplines of Yoga. Though many of them are believed in literally by contemporary Yogis, it is obvious that they are not the primary concern or aim of practical Yoga. Some of the classic claims are explained as familiar metaphors, others as possible benefits, but emphasis is put by the Yogi (at least, by my teacher) on the more tangible and direct benefits of body and mind. In what follows I have attempted to be as specific as possible in reproducing the interpretation of aims given by my own teacher, regardless of literary tradition.

There is not a single ãsana that is not intended directly or indirectly to quiet the mind; however, for the advanced meditation practices of Yoga there are only two postures that are considered essential. These are siddhãsana and padmãsana. The other ãsanas have been devised to build up different parts of the body and to develop the needed strength that is required by the rigid physical disciplines imposed upon the student. The postures are also used to keep the body in good health and to help the beginner overcome the monotony of his extremely sedentary life.

The teacher emphasizes that the primary purpose of the ãsanas, is the reconditioning of the system, both mind and body, so as to effect the highest possible standard of muscular tone, mental health, and organic vigour. Hence stress is put upon the nervous and the glandular systems. Hatha Yoga is interpreted as a method that will achieve the maximum results by the minimum expenditure of energy. The various ãsanas have been devised primarily to stimulate, exercise, and massage the specific areas that demand attention. With these ãsanas, therefore, my account will begin.