|

ENERGY

|

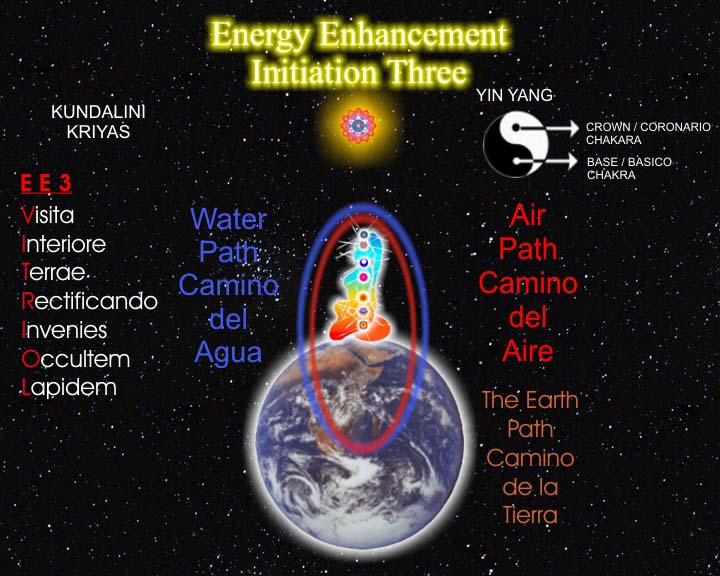

GAIN ENERGY

APPRENTICE

LEVEL1

|

THE

ENERGY BLOCKAGE REMOVAL

PROCESS

|

THE

KARMA CLEARING

PROCESS

APPRENTICE

LEVEL3

|

MASTERY

OF RELATIONSHIPS

TANTRA

APPRENTICE

LEVEL4

|

2005 AND 2006

|

PsychopathTHE MASK OF SANITYSection 2: The MaterialPart 1: The disorder in full clinical manifestations 9. George

|

9. George This man was 33 years of age at the time I first saw him and admitted him to a psychiatric hospital. He stated that his trouble was "nervousness" but could give no definite idea of what he meant by this word. He was remarkably sell-composed, showed no indication of restlessness or anxiety, and could not mention anything that he worried about. He went on to state that his alleged nervousness was caused by "shell shock" during the war. He then proceeded to elaborate on this in an outlandish story describing himself as being cast twenty feet into the air by a shell, landing in his descent THE MATERIAL 71 astride some iron pipes, and lying totally unconscious for sixty days, during all of whichhe hovered between life and death. A physical examination showed George without any evidence of injury or illness. In fact, he was a remarkably strong and active man, 6 feet tall and 170 pounds in weight. Later, in an athletic meet held on the hospital grounds, he showed himself an exceptional sprinter and broadjumper, surpassing many able competitors ten years younger than himself in these events. Prolonged observation and psychiatric study brought out no sign or suggestion of a psychosis or a psychoneurosis. Despite his original complaint of "nervousness," he was at all times calm and without the slightest evidence of abnormal anxiety. He ate and slept well, did not complain of any worries, and was free of phobias, compulsions, conversion reactions, tics, and all other ordinary neurotic manifestations. Records of this man's career show that he has been confined in various mental hospitals approximately half the time since he became of age. In addition to periods ranging from a few weeks to six months at federal institutions in Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, and Florida, he was also frequently sent by the government to private psychiatric hospitals and invalids' homes. Between these experiences he spent a good part of his time in the local county jail or in other jails at Birmingham, Montgomery, Mobile, or other towns which he visited. He was taken in sometimes for drunkenness and disorderly conduct, at other times for writing bad checks, petty theft, reckless driving of automobiles, obtaining money under false pretenses, snatching the purse from a prostitute, taking possession of a house whose owners were off on vacation, and similar actions. Extravagant but insincere threats to harm his wife and four children made after taking a few drinks and lunacy charges also accounted for a dozen or so arrests. During all the observation at various hospitals mentioned previously, as well as at a state mental hospital where George also spent a short time, no technical evidence of a psychosis or a psychoneurosis is mentioned. His wife and friends have repeatedly persuaded local authorities to consider him as mentally deranged and to have him sent to hospitals rather than let him face the various charges brought against him from time to time. On other occasions, when he was refused admission by hospitals where physicians had already studied him more than once and declared him sane, competent, and not in need of psychiatric treatment, friends and relatives have had him arrested, have prevailed upon local doctors to sign statements that he is deranged and dangerous, and have brought pressure to bear so that hospitals, in the light in which the case was presented, had no choice but to readmit him. The doctors involved in such procedures, country practitioners for the 72 THE MASK OF SANITY most part, never mention technical evidence that would indicate a psychosis or a psychoneurosis as they are described in the textbooks. Such statements as these are typical: Something is decidedly wrong mentally. I don't think I have ever come in contact with a man as unreliable as he is. He worries everybody that has fooled with him until they hate him. The County authorities are tired of boarding him as he is not a criminal. (Family Physician) Everybody who comes in contact with him agrees that he should be confined permanently ... very unreliable as to his word of honor. (County physician) A physician who owns a private hospital located at a town nearby, in explaining his refusal to accept the patient again, ends by saying "we do not cater to his class." He is described as frequently drinking whiskey to excess and as sometimes taking Veronal, Luminal, Amytal, and bromides to ease himself in the aftermath of a spree. Although there is no record of alcoholic hallucinations, many bizarre and notable actions are described when the patient has had something to drink. On a cold February day he rushed, fully clothed, down to the creek and sprang in. After thrashing about, yelling and cursing to no purpose and creating a senseless commotion, he swam back to land without difficulty. One fine spring evening he is said to have run entirely naked through the streets of the town. He once sat up all night under the house striking matches aimlessly. Generally believed reports indicate that late one night he, with several drinking companions, succeeded in releasing a half-tamed bear from the cage in which it was kept at a filling station to attract trade. A good deal of fright, some civic uproar, and hasty precautionary measures ensued. Assiduous and painstaking effort by a number of local volunteers led to the bear's relatively uneventful return to his cage. According to available information, the bear was not terribly dangerous but sufficiently so to make a man of anything like ordinary responsibility sharply restrain all impulses to loose him on the outskirts of an unprepared community. The patient denied having been a party to this exploit but the evidence against him is strong. In view of this man's failure to make any effort to conduct himself sensibly through so many years, there is no wonder that many are found to say that he is of unsound mind. He has done no work except for occasional periods when for a week or ten days he would show considerable promise in such occupations as automobile salesman, clerk in a grocery store, soda THE MATERIAL 73 jerk, or bootlegger's assistant. It was not long before he proceeded, in the language of an elderly uncle often called on to deal with these problems, to "launch himself on another pot-valiant and fatuous rigadoon." After studies of his case were completed, and on the basis of his cooperative and technically sane behavior, he was given parole privileges. He promised, of course, not to drink or to break any other rule of good conduct and expressed many fine intentions positively and reassuringly. Six days later he staggered into his ward and attempted to go to bed without being noticed by the attendant. On being found so plainly "in his cups," he raged petulantly, first denied any contact with stimulants, and finally, with indignation, admitted having taken one-half glass of beer. His eyes were bloodshot, he could scarcely stand, and he spoke in wild, boastful, almost unintelligible accents. A bottle of cheap whiskey was discovered hidden under his mattress. According to the custom of the hospital, George was now confined to a closed ward where his superficial sanity stood out arrestingly from the delusional babbling and the blank-faced, staring inertia of his psychotic fellows. He was always intelligent and agreeable, frequently pointing out the obvious inconsistency of his being confined among "insane" people. Pleading important business downtown, he was, after three weeks, given a pass to go out in the care of a hospital attendant for a few hours. He returned in good condition, but when night came on, he refused to go to bed, cursed, and spat at the nurse who tried to advise him. His breath reeked of raw liquor, and a search disclosed a half-empty pint bottle in his pocket. The attendant who took him to town denied having allowed him to purchase whisky and could only surmise in astonishment that the patient must have slipped off for a moment and obtained the bottle while pretending to go to the toilet. A few weeks after this incident, the patient's wife came to town and asked to take him out on a pass, agreeing to assume full responsibility. When she returned him to the hospital, it was evident that he had drunk liberally, and the wife confessed herself as having been unable to deal with him. The next day a man living near the hospital advised that he had fired a revolver at the patient on being alarmed by his behavior. George, after loitering about the premises boisterous and vaguely threatening, began to fumble at a window as if trying to force his way in. The shot had not been aimed at George but only in his general direction in order to frighten him. This end was satisfactorily achieved, for at the report he made off in a clatter of undignified haste. About a month later, on strong promises of good behavior, George was 74 THE MASK OF SANITY again given parole. Within a few days he climbed over the fence and hired an automobile. After racing in this for a while about the road to no special purpose, he wrecked it in the city streets and was taken to jail. This cycle of events was repeated several more times. The man was obviously not where be belonged when confined on a closed ward with extremely psychotic patients of the ordinary type, just as plainly he showed himself unable to remain on an open ward with mildly psychotic patients who succeeded in adapting themselves to a life of limited freedom. Finally, on being kept under close supervision for several weeks following a senseless and troublesome spree, he demanded his discharge in a wellwritten letter emphasizing his sanity and the inappropriateness of his hospitalization. He was released accordingly. Six months later he was sent back to the hospital from the local jail, where he had been confined after striking a Negro man with a shovel. He had, as was his wont, been drinking but showed little evidence of being affected by alcohol. The other man was walking peacefully by when our patient engaged him in a dispute about possession of the pavement. "Flown with insolence and [perhaps] with wine," he found the other's conciliatory attitude not to his taste, waxed more overbearing, and ended by felling his presumed adversary with a deft blow. He did not on this occasion seem to lose control of himself like a man in a genuine rage who might have struck blow after blow. His deed seemed prompted more by fractiousness and impulses to show off than by violent passion. His application for admission was at first refused by the hospital, since only patients suffering from mental disorder in the commonly accepted sense are eligible. His wife and influential friends thereupon invoked higher authorities, who arranged for him to be taken. This time he was again found to be free from all symptoms of recognized mental disorder, and his condition was classified in the following terms: (1) no nervous or mental disease and (2) psychopathic personality. He did not complain of nervousness as he had at the time of his first admission but instead insisted that he was a sane and well man and demanded full privileges to come and go as he pleased, saying that the authorities who arranged for him to come to the hospital had promised him this. It was plain that George regarded the hospital simply as an expedient by which he might escape the legal consequences of his behavior. After being kept for a few weeks on a closed ward, he was allowed to go out on the grounds alone with the understanding that after a few days he would be discharged as sane and competent. He could not, however, keep out of trouble. On the third day of his freedom he was seen by the guard driving at high speed through the gate in a car belonging to one of the physicians. THE MATERIAL 75 Chase was offered, and after a lively race he was overtaken about fifteen miles from the hospital, having battered in a fender and knocked off a headlight of the car on the way. It is hardly necessary to point out that this man had repeatedly been instructed in the rules to be observed while on parole, that he knew the driving of an automobile by a patient in this hospital to be a serious violation of his trust, not to speak of the theft, or the unauthorized borrowing he proclaimed it to be. When finally caught, he appeared as sane as before, showing no evidence of any episodic loss of his usual reasoning power. He had not been drinking when he took the automobile and, of course, the pursuit was too hot for him to obtain liquor while in flight, though in view of his previously demonstrated ingenuity and dispatch in fulfilling this want, it would scarcely have been surprising to find him properly rattled. On his return to the hospital, he did not show the slightest sign of remorse over having taken possession of and having succeeded in damaging the car belonging to a physician who had always been particularly kind to him. The owner's willingness to free him from responsibility for his deed he took as a matter of course, expressing neither gratitude nor satisfaction. In fact, he dismissed the whole matter as insignificant, and his prevailing attitude was that of a man generally ill used. Some weeks later he was sent home. About six months afterward his wife telegraphed the hospital that she could no longer cope with her husband, whom she described as being still in such folly as that already recounted. He did not, however, arrive by the train he boarded. It was subsequently learned that he got off along the way, obtained a few drinks, and made a clamorous nuisance of himself in the station until the police came to cut short his activities. A little later he was readmitted following a series of misadventures in no way different from those already mentioned but including a period in the state mental hospital. He was alert and rational and just as he had always been before, except for the presence of a urethral discharge of gonococcic origin. He gave a false account of his activities, saying that he had been working on a farm and had been in no trouble at all. The records showed that he had not turned his hand to make an honest dollar since he left and that a week had seldom passed without his buffoonish or antisocial activities arousing consternation in the neighborhood and bringing him to the attention of the police. He was freely communicative and scarcely waited for encouragement to give an explanation of how he came by his gonorrhea. The records show that after causing some commotion in town by maudlin or threatening outbursts on the streets and silly, pompous threats about harming his wife, he 76 THE MASK OF SANITY had been brought in, bedraggled and disconsolate, from a ditch where he lay and confined to jail. The jail, George said, was crowded, and the jailer, who knew him to be a good fellow, placed him in a cell on the women's section of the building. The bars of his cell were about six inches apart and so, according to his story, he was separated from and yet provocatively close to the women prisoners. These, his neighbors, were seven girls ranging from 14 to 20 years of age and awaiting transportation to the women's reformatory. He said that at night, when the lights were out, these girls would disrobe and, coming to the bars, would entice him, calling him "pretty boy" and "country boy" and otherwise teasing and challenging him until he began to indulge in sexual intercourse with them between the bars in order to make them leave him alone. He says that he continued this practice with each of them every night during the rest of his sojourn there, the transactions taking place always in the dark and through the separating barrier. From one or all of these women he says he caught the gonorrhea which now troubled him. He appeared to be no little proud of this story, which, however, is probably no more accurate than his stories of exemplary behavior and hard work or his frequently expressed intentions to conduct himself like a sensible person. Prolonged observation of the patient in the hospital showed him to be more prone to drift about street corners and bars, to indulge in petty gambling or theft, to cadge and impose on chance acquaintances, or to raise some puerile and futile clamor than to seek intercourse with one woman, much less with many. Since this last admission, his story has been the same as before. On recovering from gonorrhea, he was, after being found sane and competent, given freedom of the grounds. He soon left without permission and was found in the hands of the police. Back again on a closed ward he was dissatisfied and with irrefutable arguments pointed out the incongruity of his being assigned to a place among men content to sit all day in silence staring blankly at nothing or who murmured incessantly that their heads were full of gold, radium, and diamonds, that they had no stomachs or intestines, that the Masons were playing on their sexual organs by radio, that they were sickened by the odor of the bells. It was here, however, that George had to be kept, a perfectly clear-minded person, neat, polite, and quick witted, in striking contrast to his fellows, whose lips moved inarticulately as they responded to hallucinatory voices and some of whom urinated and defecated on themselves, sought to eat dead roaches, etc. This was not, of course, an ideal environment for him. He was therefore THE MATERIAL 77 sent back to the parole ward time after time, only to prove himself unadaptable after periods ranging from a few days to a few weeks. When put on the closed ward among better adjusted patients with schizophrenia or dementia paralytica, men who worked on a farm detail or at woodwork, he took advantage of his situation and escaped. During much of his time in the hospital it has therefore been necessary to keep him among the actively disturbed, badly deteriorated patients where supervision is complete and possibilities of escape are limited. When last heard from, he was again hospitalized. Opportunities are continually offered him to improve his situation. From time to time parole is restored, and occasionally his wife takes him home on furlough. Always, however, he causes trouble for himself and others and always for no discernible purpose. The last news of him was that he violated his parole by leaving the hospital. After sustaining himself by his customary activities for a week or ten days and staying clear of the police, he again came to grief. With the aim evidently of stealing a hen or a few fryers or perhaps to evade pursuit, he slipped into a Negro farmer's chicken house. Having brought along a bottle and perhaps being delayed by needs to avoid detection, he drank injudiciously. Next morning he was found in the coop, where he had apparently wallowed and groped through the night. Called by the farmer, attendants brought him to the hospital. Here on a closed ward we find him, among helpless, irrational people and subject to the strict control and attention required for those who cannot direct themselves. Though he left school after completing the eighth grade, he writes letters which would do credit to a college graduate. In these he insists on having his freedom, stating that his difficulties in the past have been minor and that he is ready and thoroughly able to settle down to an exemplary life. He often stresses the fact that his wife and children need his protection and support. His family history is entirely negative. Parents and grandparents were hardworking, sober folk, liked and respected in the little rural community in which the present generation lives. One sister and three brothers are leading normal lives there today |

Next: Section 2: The Material , Part 1: The disorder in full clinical manifestations, 10. Pierre

Energy Enhancement Enlightened Texts Psychopath The Mask Of Sanity

Section 2, Part 1

|