Mandala

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

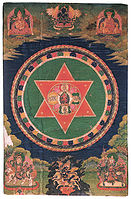

Mandala of the Forms of Manjushri.

Mandala (Skt. maṇḍala; T. dkyil ’khor; C. mantuluo; J. mandara; K. mandara 曼荼羅),[1] literally "circle"; the term is used in a variety of contexts within Buddhism, usually refering to a center and periphery.

The term mandala can have the following meanings:[2]

- an integrated structure that is organized around a central unifying principle

- within tantric practices, the sacred environment and dwelling place of a central deity, surrounded by a retinue of subordinates, which is visualized by the practitioner[3]

- the two dimensional representation of this environment on cloth or paper, or made of heaps of coloured sand

- a three dimensional representation of this environment, traditionally made of wood

- an offering of the entire universe visualized as a pure land with all the inhabitants as pure beings

- a practitioner, and the surroundinng phenomenal world

Within tantric practice

John Powers states:

- The Sanskrit term maṇḍala (dkyil ’khor) literally means “circle,” both in the sense of a circular diagram and a surrounding retinue. In Buddhist usage the term encompasses both senses, because it refers to circular diagrams that often incorporate depictions of deities and their surroundings. The mandala represents a sacred realm—often the celestial palace of a buddha—and it contains symbols and images that illustrate aspects of the awakened psychophysical personality of the buddha and that indicate Buddhist themes and concepts. The Dalai Lama explains that the image of the mandala “is said to be extremely profound because meditation on it serves as an antidote, quickly eradicating the obstructions to liberation and the obstructions to omniscience as well as their latent predispositions.”[4] The obstructions to liberation and the obstructions to omniscience are the two main types of mental afflictions that inhibit one’s attainment of buddhahood. The maṇḍala serves as a representation of an awakened mind that is free of all such obstacles, and in the context of tantric practice it is a powerful symbol of the state that meditators are trying to attain.[5]

Chogyal Namkhai Norbu explains the meaning of the mandala in the context of the tantric "path of transformation":

- What do we mean by "transformation"? We are referring to the potentiality a realized being has to manifest infinite forms in the Sambhogakaya, which forms are related to the type of beings who will perceive the transmission. At this point it is necessary to have a clear understanding of what the Sambhogakaya dimension is. Sambhogakaya, in Sanskrit, means "body" or "dimension" of wealth, the wealth being the infinite potentiality of manifestations of wisdom. This potentiality is comparable to that of a mirror at the centre of the universe which reflects all the different types of beings. Sambhogakaya manifestations are beyond time and beyond the limits of the material dimension, and their arising does not depend on there being any intention on the part of a realized being. What this means is that the manifestation of the Kalachakra divinity was not something created by the Buddha at a given moment of historical time, but is something that always existed, because the Sambhogakaya dimension is beyond time. Those who received transmission of it, through the pure perception of a manifestation of the Buddha, explained it in words and symbols, thus giving rise to the Kalachakra.

- The visual representation of a manifestation of transformation is called a mandala, which is one of the fundamental elements of the practice of tantra. The mandala could be said to be like a photograph taken at the moment of the pure manifestation of the divinity. At the center of every mandala one finds the central divinity, who represents the primordial condition of existence, corresponding to the element of space. At the four cardinal points, represented by the colours of the other four elements, there will be the same number of forms of divinities, symbolizing the functions of wisdom which arise as the four actions.

- The divinity of a mandala will not always have a human appearance, but sometimes will have one or more animal heads and a corresponding number of arms and legs. This has been interpreted by many scholars as a symbolic way of representing the principles of the tantra in question. But such considerations are, in fact, only of relative and partial importance. The truth is that all manifestations of divinities arise from the Sambhogakaya dimension and since, as we have already explained, the Sambhogakaya is like a mirror, it reflects every type of being that appears to it. Thus, the so-called "Art of Tibetan Tantra" could really be seen as a kind of evidence that there do exist different types of beings all over the universe.[6]

Gallery

Painted 19th century Tibetan mandala of the Naropa tradition, Vajrayogini stands in the center of two crossed red triangles, Rubin Museum of Art

Painted Bhutanese Medicine Buddha mandala with the goddess Prajnaparamita in center, 19th century, Rubin Museum of Art

Mandala of the Six Chakravartins

Vajravarahi Mandala

References

- ↑ Robert E. Buswell Jr., Donald S. Lopez Jr., The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton: 2014), s.v. maṇḍala

- ↑

Mandala, Rigpa Shedra Wiki

Mandala, Rigpa Shedra Wiki

- ↑ Powers, John. Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Ithaca: Snow Lion, 2007, p. 254

- ↑ The quote is from Tantra in Tibet: The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra - Vol. 1, p. 77

- ↑ Powers, John. Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Ithaca: Snow Lion, 2007, p. 262-263

- ↑ Chogyal Namkhai Norbu 1996, chapter 2.

Further reading

- Brauen, Martin. (1997). The Mandala, Sacred circle in Tibetan Buddhism Serindia Press, London.

- Bucknell, Roderick & Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. Curzon Press: London. ISBN 0-312-82540-4

- Cammann, Schuyler V. (1950). Suggested Origin of the Tibetan Mandala Paintings The Art Quarterly, Vol. 8, Detroit.

- Cowen, Painton (2005). The Rose Window, London and New York, (offers the most complete overview of the evolution and meaning of the form, accompanied by hundreds of colour illustrations.)

- Crossman, Sylvie and Barou, Jean-Pierre (1995). Tibetan Mandala, Art & Practice The Wheel of Time, Konecky and Konecky.

- Dalai Lama and Tsongkhapa (2016). The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra, Volume One, Revised Edition, Snow Lion.

- Fontana, David (2005). "Meditating with Mandalas", Duncan Baird Publishers, London.

- Gold, Peter (1994). Navajo & Tibetan Sacred Wisdom: The Circle of the Spirit. ISBN 0-89281-411-X. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International.

- Powers, John (2007). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism. Ithaca: Snow Lion, p. 262-265

- Tucci,Giuseppe (1973). The Theory and Practice of the Mandala trans. Alan Houghton Brodrick, New York, Samuel Weisner.

- Vitali, Roberto (1990). Early Temples of Central Tibet London, Serindia Publications.

- Wayman, Alex (1973). "Symbolism of the Mandala Palace" in The Buddhist Tantras Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mandalas.

What Is a Mandala?, StudyBuddhism

What Is a Mandala?, StudyBuddhism- Introduction to Mandalas

- Expnation of Vajradhatu Mandala by Dharmapala Thangka Centre

- Mandalas in the Tradition of the Dalai Lamas' Namgyal Monastery by Losang Samten

- Mandala Resource Page at Himalayan Art

- 'Mandalas: An Introduction, Painting & Sculpture' by Jeff Watt

- The Maṇḍala by Chris Bell (virginia.edu)