Eight worldly concerns

The eight worldly concerns or eight worldly dharmas (Skt. aṣṭalokadharma; P. aṭṭhalokadhamma; T. འཇིག་རྟེན་ཆོས་བརྒྱད་, ‘jig rten chos brgyad) are a set of worldly or mundane concerns that generally motivate the actions of ordinary beings.[1] They are:

- hope for pleasure and fear of pain,

- hope for gain and fear of loss,

- hope for praise and fear of criticism,

- hope for good reputation and fear of bad reputation.

Preoccupation with these worldly concerns is said to be an obstacle to genuine spiritual practice.

Ringu Tulku states:

- Real dharma practice is free from the eight worldly concerns. To review the eight worldly concerns, they are being rich or poor, which could also be described as gain or loss; being powerful or powerless; having a good reputation or a bad reputation; and having pleasure or pain. Usually, we think that happiness comes from wealth, power, popularity, and pleasure, and that these four things will give us everything that we need—we will have “made it.” But from a spiritual point of view, these things are not the answer. Being rich is not a source of happiness, and being poor is not a source of happiness. Being powerful does not bring happiness, and being powerless does not bring happiness. It is the same with being well-known or unknown, and having pleasure or pain. Lasting peace and happiness do not depend on outer conditions; they come from seeing in a clear way. When your mind is focused on any of the eight worldly concerns, whether on the positive side or the negative side, your activities are not following the dharma.[2]

The eight concerns

The eight worldly concerns are, in brief:[3]

- Hoping for positive circumstances

- 1. Hope for pleasure (physical comfort and mental happiness)

- 2. Hope for gain (material wealth and prosperity)

- 3. Hope for praise (heard directly)

- 4. Hope for a good reputation or fame (in one’s society)

- Fearing negative circumstances

- 5. Fear of pain (physical and mental)

- 6. Fear of loss (material wealth and prosperity)

- 7. Fear of criticism (heard directly)

- 8. Fear of having a bad reputation (in one’s society)

Contemporary explanations

B. Alan Wallace

B. Alan Wallace states:

- These eight worldly concerns are: gain and loss, pleasure and pain, praise and criticism, and fame and disgrace.

- These are the concerns that pervade most people's daily lives. They are pervasive precisely because they are mistaken for effective means to attain happiness and to avoid suffering. For example, many of us, driven by the concerns of gain and loss, work to acquire an income so that we can buy the things that money can buy, some of them necessities but often many of them unnecessary things that we believe will bring us happiness. We also earn money so that we can avoid the misery and humiliation of poverty.

- Again, experiencing pleasure and avoiding pain are the primary motivations for a majority of our activities. We engage in many actions — some of which may seem spiritual — for the sake of immediate satisfaction or relief. For example, if we have a headache we may take aspirin, or sit and meditate hoping the headache will go away. These remedies may lead to temporary relief from discomfort, but that is where their effectiveness ends.

- Praise and criticism is the next pair of worldly concerns, and even a little reflection reveals the great extent to which our behavior is influenced by desire for praise and fear of criticism. The final pair, fame and disgrace, includes seeking others' approval, affection, acknowledgment, respect, and appreciation, and avoiding the corresponding disapproval, rejection, and so on.

- The reason for drawing attention to these eight worldly concerns is not to show that they are inherently bad. It is not bad to buy a car, enjoy a fine meal, to be praised for one's work, or be respected by others. Rather, the reason for pointing them out is to reveal their essentially transient nature and their impotence as means to lasting happiness.[4]

Traleg Kyabgon Rinpoche

Traleg Kyabgon Rinpoche states:

- Nagarjuna states that we have to be careful in terms of how we understand these sets of factors. We should not think the “eight worldly dharmas” means that we should not have them or that we should go out of our way not to gain anything, or not think that being praised is better than being denigrated. It means that we should not look for them too much and we should not care too much whether people are praising us or putting us down or that one wants any kind of pain. It also means that we should be able to handle losses when they occur and not be thrown into a deep state of depression or despair. As Nagarjuna states, even highly advanced spiritual people still experience all of these things. They may experience gain, praise, and all of these things. They are not shunned; it does not mean that one has to shun them. What it does mean is that one should not be obsessed about going overboard in terms of trying to have more wealth and more properties or trying to make sure that people are praising us and not denigrating us. This is another thing that a Buddhist practitioner should try to find a balance with. Being in the world, we cannot avoid them. Again, it is about attitude; it is how we handle the “eight worldly dharmas” that determines whether we are going to lead a good life or a bad one.[5]

Thubten Chodron

Thubten Chodron states:

- These eight worldly concerns are a huge problem. They’re the first level of things that we really have to deal with in our practice. Like I told you last time, my teacher Zopa Rinpoche would do a whole month-long mediation course on the eight worldly concerns really to emphasize to us to pay attention to these. If we don’t work on these eight, what else are we going to work on? We say that we are Dharma practitioners, well, if we’re not working on overcoming these eight, then what are we doing in our Dharma practice? What are we working to overcome if it’s not these basic principal eight things that come at the beginning? How are we going to overcome dualistic appearances if we can’t even give up our chocolate? How are we going to overcome selfishness if we cannot endure a little bit of criticism, or whatever? So if we’re not working on these eight, then we have to ask ourselves, “What am I doing in my practice? What does practicing Dharma mean?” Practicing Dharma means transforming our mind. It doesn’t mean just looking on the outside like we’re a Dharma practitioner. It means actually doing something with our mind. These eight are the foundation that we really have to work with—so plenty of work to do here.[6]

Geshe Sonam Rinchen

Geshe Sonam Rinchen states:

- Letting go of our preoccupation with the things of this life involves giving up the eight worldly concerns, which in short depends on overcoming attachment to food, clothing and reputation. Many meditators, scholars and monks happily forego good food and clothing, and live a simple life, yet they remain attached to a good reputation, which is hardest to give up. Above the entrance to the cave it may say, "Retreat in progress. Do not disturb," but inside the retreatant is hoping for recognition as a great meditator. The scholar has hopes of acclaim for his great knowledge and the monk for his pure morality. Such thoughts attract obstacles and prevent anything valuable from being accomplished. If letting go of our attachments is the door to pure practice, we must look within and see where we stand. It is not easy to be a true practitioner.[7]

Quotations

Worldly Concerns Sutra

Gain and loss, fame and disgrace, praise and criticism, pleasure and pain. These eight worldly concerns revolve around the world, and the world revolves around these eight worldly concerns.[8]

Gain and loss, fame and disgrace,

praise and criticism, and pleasure and pain.

These qualities among people are impermanent,

transient, and perishable.

A clever and mindful person knows these things,

seeing that they’re perishable.

Desirable things don’t disturb their mind,

nor are they repelled by the undesirable.

Both favoring and opposing

are cleared and ended, they are no more.

Knowing the stainless, sorrowless state,

they understand rightly, going beyond rebirth.[9]

Nargarjuna

The World Knower[10] has said:

Gain and loss, pleasure and pain,

Pleasant words and unpleasant words, praise and criticism—

These are the eight worldly concerns.

Do not allow these concerns occupy your mind;

Regard them with equanimity.[11]

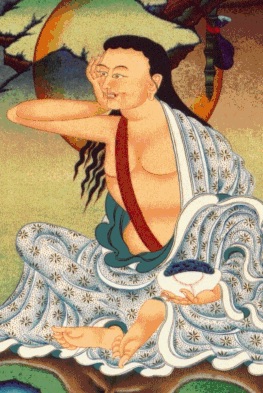

Milarepa

My system is to eradicate the belief in the self, to cast the eight ordinary concerns to the winds, and to make the four demons feel embarassed.[12]

— Milarepa

What the Lord of Men, the Conqueror,[13] mainly taught

Was how to be rid of the eight ordinary concerns.

But those who consider themselves learned these days--

Haven't their ordinary concerns grown even greater than before?

The Conqueror taught rules of discipline to follow

So that one could withdraw from all worldly tasks.

But the monks of today who follow those rules--

Aren't their worldly tasks not more numerous than before?

He taught how to live like the rishis of old

So that one could cut off ties with friends and relations.

But those who live like rishis these days--

Don't they care how people see them even more than before?

In short, all dharma is useless

If practiced without remembering death.[14]— Milarepa

Gampopa

The precious guru said: Whatever good dharma practice you do—whether study, reflection, listening, teaching, keeping the precepts, accumulation, purification, or meditation—should not become just another activity. Instead, dharma practice should be transformative. If you wonder what this means, a scripture says:

- Attachment, anger, and delusion

- And the actions created by them are unvirtuous.

As well, even virtuous deeds are ordinary actions if they are done to obtain the happiness of gods and humans in this life, or if your intention is degraded or based on the eight worldly concerns.[2]

— Heart Advice by Gampopa

Tsele Natsok Rangrol

Finally, although various authoritative scriptures and oral instructions have taught different types of conduct as means to enhance one’s practice, the essential key points are as follows:

- Cut your worldly attachments completely and live companionless in secluded mountain retreats; that is the conduct of a wounded deer.

- Be free from fear or anxiety in the face of difficulties; that is the conduct of a lion sporting in the mountains.

- Be free from attachment or clinging to sense pleasures; that is the conduct of the wind in the sky.

- Do not become involved in the fetters of accepting or rejecting the eight worldly concerns; that is the conduct of a madman.

- Sustain simply and unrestrictedly the natural flow of your mind while unbound by the ties of dualistic fixation; that is the conduct of a spear stabbing in space.[15]

— Lamp of Mahamudra by Tsele Natsok Rangdrol

Drikung Bhande Dharmaradza

The eight worldly concerns are like a snare.

Exhausted by meaningless effort, we end our lives in dissatisfaction.

Meditate well on renunciation.

This is my heart advice.[16]— The Jewel Treasury of Advice by Drikung Bhande Dharmaradza

Chatral Rinpoche

No matter where you stay, be it a busy place or a solitary retreat,

The only things that you need to conquer are mind’s five poisons

And your own true enemies, the eight worldly concerns,

Nothing else.

Whether it is by avoiding them, transforming them, taking them as the path, or looking into their very essence,

Whichever method is best suited to your own capacity.[17]— Words of Advice from Chatral Rinpoche

Alternate translations

- eight worldly concerns (Ringu Tulku, Thubten Chodron, B. Alan Wallace, et al)

- eight worldly preoccupations (Rigpa wiki)

- eight mundane obsessions

- eight worldly dharmas

- eight mundane dharmas (Buswell and Lopez)

- eight ordinary concerns (Padmakara)

- eight transitory things of the world (Alexendar Berzin)

- eight worldly conditions (Bhikkhu Sujato, Bhikkhu Bodhi)

- eight vicissitudes of the world (Piyadassi Thera)

- eight worldly winds

Suttas

The eight worldly concerns are referenced in the following suttas:

- Worldly Conditions Sutta (AN 8.6)

Ṭhāna Sutta (AN 4:192), SuttaCentral

Ṭhāna Sutta (AN 4:192), SuttaCentral

See also

Videos

YouTube videos

Search for videos:

- Search YouTube for: Eight worldly concerns Buddhism

Selected videos:

- What's Wrong With Our 'Worldly Concerns'? - Ringu Tulku Rinpoche

- Description: What is it that is actually wrong with the so called Eight Worldy Dharmas - with our usual way of pursuing things? It's our expectation that they will bring us true happiness. And then we get lots of problems... An excerpt from a recent teaching given by Ringu Tulku Rinpoche.

- Working with the Eight Worldly Concerns - BBCorner

- Description: Venerable Thubten Jigme shares points of inspiration from Geshe Sonam Rinchen to spur us on to work with our attachment to the eight worldly concerns.

YouTube playlists

Notes

- ↑ Eight worldly dharmas (Glossary of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ringu Tulku 2012, p. 35.

- ↑ Dzigar Kongtrul 2020, Appendix B.

- ↑ Wallace & Wilhelm 2016, Chatper 1.

- ↑ Traleg Kyabgon 2017, "Regarding the Eight Worldly Dharmas Equally".

- ↑ The eight worldly concerns (thubtenchodron.org)

- ↑ Geshe Sonam Rinchen 1999, Chapter 1. The Wish for Freedom.

- ↑ Dalai Lama & Thubten Chodron 2018, s.v. Chapter 8.

- ↑

Worldly Conditions; AN 8.6, SuttaCentral

Worldly Conditions; AN 8.6, SuttaCentral

- ↑ "World Knower" is an epithet for the Buddha.

- ↑ Provisional translation.

- ↑ Patrul Rinpoche 1998, p. 305.

- ↑ "Lord of Men" and "Conqueror" are epithets for the Buddha.

- ↑ Patrul Rinpoche 1998, pp. 90-91.

- ↑ Tsele Natsok Rangdrol 2009, p. 68.

- ↑ Kenchen Konchog Gyalsten Rinpoche 2009, p. 89.

- ↑

Words of Advice from Chatral Rinpoche, Lotsawa House

Words of Advice from Chatral Rinpoche, Lotsawa House

Sources

Dalai Lama; Thubten Chodron (2018), The Foundation of Buddhist Practice, The Library of Wisdom and Compassion, Volume 2, Wisdom Publications

Dalai Lama; Thubten Chodron (2018), The Foundation of Buddhist Practice, The Library of Wisdom and Compassion, Volume 2, Wisdom Publications- Dzigar Kongtrul (2020), Waxman, Joseph, ed., Peaceful Heart: The Buddhist Practice of Patience, Shambhala Publications

- Geshe Sonam Rinchen (1999), The Three Principle Aspects of the Path, Snow Lion

- Kenchen Konchog Gyalsten Rinpoche (2009), The Complete Guide to the Buddhist Path, Snow Lion

Patrul Rinpoche (1998), Words of My Perfect Teacher, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Altamira Press

Patrul Rinpoche (1998), Words of My Perfect Teacher, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Altamira Press- Ringu Tulku (2012), Confusion Arises as Wisdom: Gampopa's Heart Advice on the Path of Mahamudra (Kindle Edition ed.), Shambhala Publications

- Traleg Kyabgon (2017), Letter to a Friend: Nagarjuna's Classic Text, Shogum Publications

- Tsele Natsok Rangdrol (2009), Heart Lamp: Lamp of Mahamudra & The Heart of the Matter, translated by Pema Kunzang, Erik, Rangjung Yeshe Publications

- Wallace, B. Alan; Wilhelm, Steven (2016), Tibetan Buddhism from the Ground Up, Wisdom Publications

Further reading

Texts:

- Robert E. Buswell Jr., Donald S. Lopez Jr., The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton: 2014), s.v. aṣṭalokadharma

Dalai Lama; Thubten Chodron (2018), The Foundation of Buddhist Practice, The Library of Wisdom and Compassion, Volume 2, Wisdom Publications, Chapter 8: The Essence of a Meaningful Life

Dalai Lama; Thubten Chodron (2018), The Foundation of Buddhist Practice, The Library of Wisdom and Compassion, Volume 2, Wisdom Publications, Chapter 8: The Essence of a Meaningful Life- Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, Into the Heart of Life, Snow Lion, 2012, Chapter 4

Thupten Jinpa, ed. (2020), Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics, Volume 2: The Mind, translated by Rochard, Dechen; Dunne, John, Wisdom Publications, Chapter 27: The Eight Worldly Concerns

Thupten Jinpa, ed. (2020), Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics, Volume 2: The Mind, translated by Rochard, Dechen; Dunne, John, Wisdom Publications, Chapter 27: The Eight Worldly Concerns

External links:

- Nyala Pema Dündul,

Advice on abandoning the eight worldly concerns, Lotsawa House

Advice on abandoning the eight worldly concerns, Lotsawa House - Renouncing the Eight Worldly Dharmas, Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

'jig_rten_chos_brgyad, Rangjung Yeshe Wiki

'jig_rten_chos_brgyad, Rangjung Yeshe Wiki 'jig_rten_pa'i_chos_brgyad, Rangjung Yeshe Wiki

'jig_rten_pa'i_chos_brgyad, Rangjung Yeshe Wiki- The eight worldly concerns (thubtenchodron.org)

- The eight worldly concerns - Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo (tricycle.org)

Worldly Conditions Sutta (2nd); AN 8.6, SuttaCentral

Worldly Conditions Sutta (2nd); AN 8.6, SuttaCentral Ṭhāna Sutta (AN 4:192), SuttaCentral

Ṭhāna Sutta (AN 4:192), SuttaCentral Piyadassi Thera (translator), The Seven Factors of Enlightenment, Access to Insight

Piyadassi Thera (translator), The Seven Factors of Enlightenment, Access to Insight