| ENERGY

|

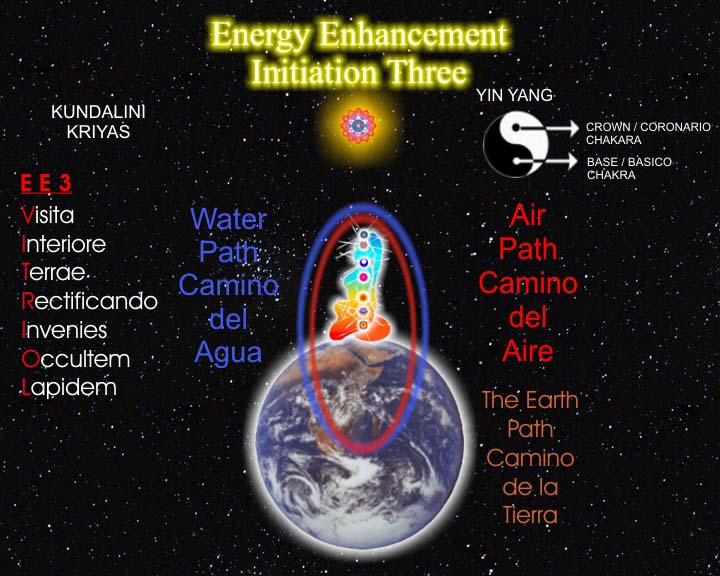

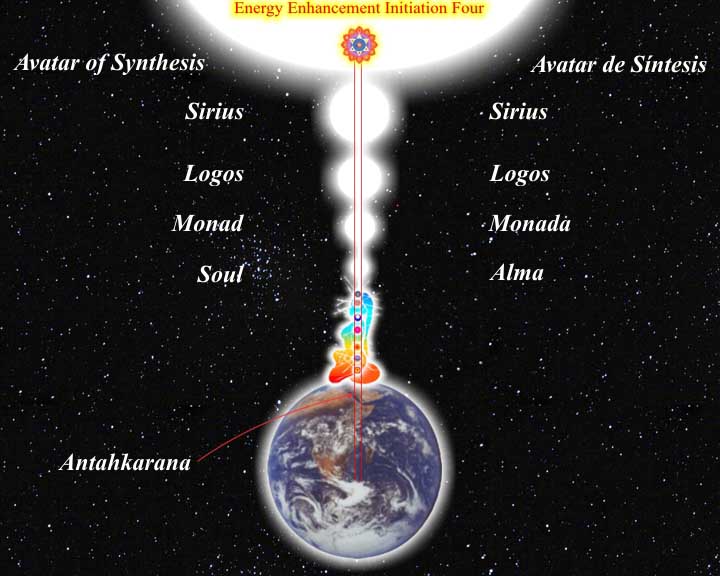

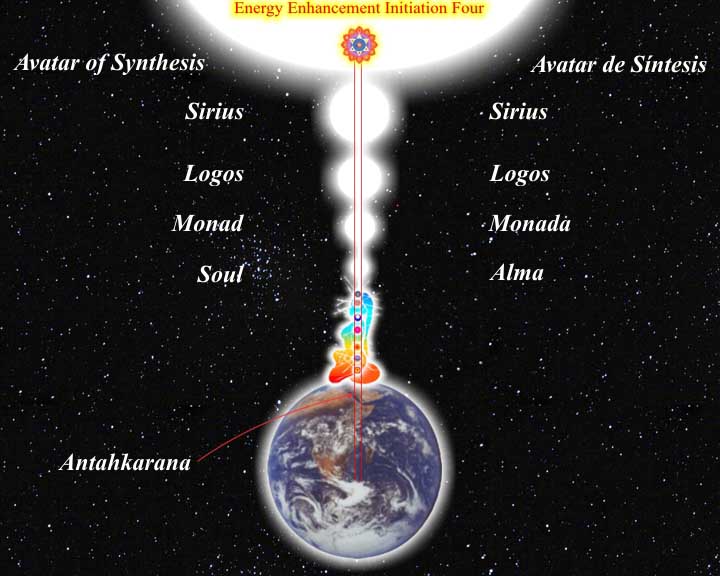

GAIN ENERGY APPRENTICE

LEVEL1

|

THE ENERGY BLOCKAGE REMOVAL

PROCESS

|

THE KARMA CLEARING

PROCESS APPRENTICE LEVEL3

|

MASTERY

OF RELATIONSHIPS TANTRA APPRENTICE LEVEL4

|

WALKING IN ZEN, SITTING IN ZEN

Chapter 8: The Head And The Heart

Question 1

Energy Enhancement Enlightened Texts Zen Walking in Zen, Sitting in Zen

The first question

Question 1

OSHO, HOW IS IT POSSIBLE THAT GURDJIEFF NEEDED ANOTHER HEAD, AN OUSPENSKY, TO WORK ON A THIRD PSYCHOLOGY, THE PSYCHOLOGY OF THE BUDDHAS, WHILE YOU WORK BY YOURSELF AND YOU CAN BE BOTH IN THE STATE OF MIND AND NO-MIND?

Prem Sanatana,

THERE HAVE BEEN TWO KINDS OF MASTERS in the world. One kind, the first, has always needed somebody else to express, to interpret, to philosophize, to communicate what the Master has experienced. Gurdjieff is not alone in that; he needed P.D. Ouspensky -- without Ouspensky he would not have been known at all. Ramakrishna comes in the same category; he needed a Vivekananda -- without Vivekananda Ramakrishna would have remained absolutely unheard of.

So has been the case with many Masters, for the simple reason that their whole work concerned the heart center. They became crystallized in the heart center -- so much so that it was impossible for them to move to the head and to use their own heads. It appeared far easier for them to use somebody else's head rather than their own.

But there was a difficulty in it. One thing was good about it: the Master himself was not constantly moving between two extremes from mind to no-mind, from no-mind to mind -- there was no movement in his being; he was absolutely crystallized. But another kind of trouble was there: the man who was being used as a medium -- Ouspensky, Vivekananda, or others -- was himself not an enlightened person. Gurdjieff could use Ouspensky's head, but not exactly the way he would have liked to. Ouspensky's own mind was bound to color Gurdjieff's experience; he was bound to bring his own prejudices, his own philosophy, his own understanding to it. He had no experience of his own, he was simply a medium. But the medium is not just an empty vehicle, he has his own mind, and anything passing through his mind is going to be changed a little bit here, a little bit there.

Ouspensky introduced Gurdjieff to the world, but he introduced Gurdjieff in his own way. One cannot blame Ouspensky. What could he do? He tried his best. I think he was one of the best interpreters that any Master has ever been able to find; but still an interpreter is an interpreter. It can't be the same; it is impossible to be the same. Hence sooner or later they had to part from each other.

In the last days of Ouspensky's life he became almost an enemy to Gurdjieff. He started saying, "Now Gurdjieff has gone mad. At first he was moving in the right direction, but the later Gurdjieff has gone astray." He could not say that the whole of Gurdjieff's teaching was wrong because his own teaching was based on Gurdjieff's teaching, but he divided Gurdjieff in two: the first part of Gurdjieff -- when Ouspensky was with him -- was right and the later part was wrong. In fact, the later part was the culmination of the first part.

But why did this happen? It was almost bound to happen because sooner or later Ouspensky's own mind was going to become a barrier. When he first came to Gurdjieff he was absolutely surrendered to him -- surrendered in the sense that he was fascinated by his personality, fascinated intellectually -- because he was a great intellectual -- absolutely surrendered in the intellectual sense, not in the existential sense. If he had been existentially surrendered he would have been of no use because Gurdjieff needed a head, he was in search of a head. He had many other followers who were devoted to him from their very innermost core, but they were not going to become his interpreters to the world.

When Ouspensky came to Gurdjieff he was already a world-famous mathematician, a philosopher. His own book, TERTIUM ORGANUM, had already been translated into almost all the great languages of the world. And that book, TERTIUM ORGANUM, is really something tremendous; coming out of a man who was unenlightened it is almost a miracle. Intellectually he managed something which nobody has ever been able to manage. He knew nothing, he had not experienced anything, but his intellectual grasp... his intellect was really sharp. He belongs to the topmost intellectuals of the whole history of humanity; there are very few competitors to rival him. Only once in a while....

Socrates had such a man, Plato. Socrates was the heart of the teaching, Plato was the head. Exactly the same was repeated in the case of Gurdjieff: Gurdjieff was the heart, Ouspensky became the head. And if I have to choose between the two my choice will be Ouspensky, not Plato. Ouspensky is simply unbelievable; his insight, without any self-realization, is so accurate that anybody who has not experienced will think that Ouspensky was a Buddha, a Christ. Only a Buddha will be able to detect the flaws, not anyone else. The flaws are there but ordinarily undetectable.

He started writing books on Gurdjieff. He wrote one of his greatest contributions, IN SEARCH OF THE MIRACULOUS, then he wrote THE FOURTH WAY. And these two books introduced Gurdjieff to the world; otherwise, he would have remained an absolutely unknown Master. Maybe a few people would have come in personal contact with him and would have been benefited, but Ouspensky made him available to millions.

But as those books spread all over the world and thousands of people started moving towards Gurdjieff, Ouspensky also became very egoistic -- naturally, because he was the cause of the whole thing. In fact, he started thinking, "Without me, what is Gurdjieff? Who is Gurdjieff without me? Who was he? When I met him he was just a refugee living in a refugee camp in Constantinople, almost starving. Nobody had ever heard about him. I have made him world famous; the whole credit goes to me." This idea went to his head -- it became too much for him -- and in subtle ways he started to dominate the movement. And you cannot dominate a man like Gurdjieff, you cannot dictate to a man like Gurdjieff. They had to part.

In the last days of his life Ouspensky was so against Gurdjieff that he would not tolerate anybody mentioning Gurdjieff's name to him; in his presence Gurdjieff's name was not mentioned. Even in his books Gurdjieff's name was reduced to only "G"; the full name disappeared. After the break just "G" remained -- somebody anonymous, "'G' said...," not "Gurdjieff." And he made it clear, very clear: "We have parted and I have developed my own system." He started gathering his own followers. Those followers were not allowed to read Gurdjieff's books, those followers were not allowed to go and see Gurdjieff. While Ouspensky was alive he was very suspicious of anybody who wanted to go to Gurdjieff or who even wanted to study his books.

But Gurdjieff was aware that this was going to happen. Still, there was no other way; some head had to be used. Gurdjieff's work was such that he was absolutely crystallized in his heart; he could not move to the head.

So was the case with Ramakrishna. Vivekananda was an ordinary intellectual, not even of the caliber of Ouspensky, but he made Ramakrishna world famous. Ramakrishna died very early, that's why Vivekananda and Ramakrishna never parted; otherwise the parting was absolutely certain. But Ramakrishna died and Vivekananda became his whole and sole representative. He dominated all the followers, he dominated the whole movement; he became for them the representative of Ramakrishna. If Ramakrishna had lived, the same thing would have happened sooner or later because Vivekananda was just head and nothing else, nothing of the heart. Even if he talks about the heart it is just head-talk, the head talking about the heart, it is not heart-full. There is no love in it, there is no meditation in it, there is no prayer in it, just intellectual analysis. He knew the scriptures and he forced his ideas on Ramakrishna's ideas. And Ramakrishna had died so there was nobody to say no to it.

Vivekananda destroyed the whole beauty of Ramakrishna. But that was going to happen because Ramakrishna was not a man of the head at all.

But this has not always been the case. Buddha never depended on anybody else. He was capable of moving from mind to no-mind, from no-mind to mind; that is his greatness. That is a far greater achievement than that of Gurdjieff or Ramakrishna because their achievements are in a way limited. Buddha is very liquid; he is not solid like a rock, he is more fluid -- like a river.

So was the case with Lao Tzu: he never depended on anybody else, he said whatever he had to say. He said it himself, and as beautifully as it could be said. And their philosophies are bound to be far more pure because they come from the original man, they come from the original realization, from the very source; there is no VIA MEDIA. So is the case with Zarathustra, Jesus, Krishna, Mahavira.

This is the second category of Masters. The first category is easier in a way; it is easy to be crystallized at one center. It is a far more complex process, a longer and far more arduous journey, to remain alive at both extremes. These are the two extremes: the head and the heart. But it is possible. It has happened before. It is happening right now in front of you.

I live in silence, but my work consists of much intellectual communication. I live in silence, but I have to use words. But when I use words, those words contain my silence. I don't need anybody else to interpret me, hence there is a far greater possibility that whatsoever I am saying will remain pure for a longer period of time.

And now, since Buddha, many scientific developments have happened....

We don't know what Buddha actually said although he never used anybody like Ouspensky or Plato or Vivekananda; he himself was his own interpreter. But there arose a problem when he died. He spoke for forty-two years -- he became enlightened when he was about forty and then he lived to eighty-two. For forty-two years he was speaking morning, afternoon, evening. Now there were no scientific methods for recording what he was saying. When he died the first question was how to collect it all. He had said so much -- forty-two years is a long time, and many had become enlightened in those forty-two years. But those who became enlightened had become crystallized in the heart because that is easier, simpler, and people tend to move to the simplest process, to the shortcut. Why bother? If you can reach a point directly, straight, then why go roundabout? And when Buddha was alive there was no need for anybody else to interpret him; he was his own spokesman, so the need was never felt.

There were thousands of arhats and bodhisattvas; they all gathered. Only those were called to the gathering who had become enlightened -- obviously, because they would not misinterpret Buddha. And that's true, they could not misinterpret him -- it was impossible for them. They had also experienced the same universe of the beyond, they had also moved to the farther shore.

But they all said, "We have never bothered much about his words since we became enlightened. We have listened to him because his words were sweet. We have listened to him because his words were pure music. We have listened to him because just listening to him was a joy. We have listened to him because that was the only way to be close to him. Just to sit by his side and listen to him was a rejoicing, it was a benediction. But we did not bother about what he was saying; once we attained there was no need. We were not listening from the head and we were not collecting in the memory; our own heads and memories stopped functioning long ago."

Somebody became enlightened thirty years before Buddha died. Now for thirty years he sat there by the side of Buddha listening as one listens to the wind passing through the pine trees or one listens to the song of the birds or one listens to the rain falling on the roof. But they were not listening intellectually. So they said, "We have not carried any memory of it. Whatsoever he must have said was beautiful, but what he said we cannot recollect. Just to be with him was such a joy."

It was very difficult now -- how to collect his words? The only man who had lived continuously with Buddha for forty-two years was Ananda; he was his personal attendant, his caretaker. He had listened to him, almost every word that he had uttered was heard by Ananda. Even if he was talking to somebody privately, Ananda was present. Ananda was almost always present, like a shadow. He had heard everything -- whatsoever had fallen from his lips. And he must have said many things to Ananda when there was nobody there. They must have talked just on going to bed in the night. Ananda used to sleep in the same room just to take care of him -- he may need something in the night. He may feel cold, he may feel hot, he may like the window to be opened or closed, or he may feel thirsty and may need some water or something, or -- he was getting old -- he may feel sick. So Ananda was there continuously.

They all said, "We should ask Ananda." But then there was a very great problem: Ananda was not yet enlightened. He had heard everything that Buddha uttered publicly, uttered privately. They must have gossiped together; there was nobody else who could have said, "I am friendly with Buddha," except Ananda. And Ananda was also his cousin-brother, and not only a cousin-brother but two years older than Buddha. So when he had come to be initiated he asked for a few things before his initiation, because in India the elder brother has to be respected just like your father. Even the elder cousin-brother has to be respected just like your father.

So Ananda said to Buddha, "Before I take initiation.... Once I become your bhikkhu, your sannyasin, I will have to follow your orders, your commandments. Then whatsoever you say I will have to do. But before that I order you, as your elder brother, to grant me three things. Remember these three things. First: I will always be with you. You cannot say to me,'Ananda, go somewhere else, do something else.' You cannot send me to some other village to preach, to convert people, to give your message. This is my first order to you. Second: I will be always present. Even if you are talking to somebody privately I want to hear everything. Whatsoever you are going to say in your life I want to be an audience to it. So you will not be able to tell me,'This is a private talk, you go out.' I will not go, remember it! And thirdly: I am not much interested in being enlightened, I am much more interested in just being with you. So if enlightenment means separating from you I don't care a bit about it. Only if I can remain with you even after enlightenment, am I willing to be enlightened, otherwise forget about it."

And Buddha nodded his yes to all these three orders -- he had to, he was younger than Ananda -- and he followed those three things his whole life.

The conference of the arhats and the bodhisattvas decided that only Ananda could relate Buddha's words. And he had a beautiful memory; he had listened to everything very attentively. "But the problem is he is not yet enlightened; we cannot rely upon him. His mind may play tricks, his mind may change things unconsciously. He may not do it deliberately, he may not do it consciously, but he still has a great unconscious in him. He may think he has heard that Buddha said this and he may never have said it. He may delete a few words, he may add a few words. Who knows? And we don't have any criterion because many things that he has heard only he has heard; there is no other witness."

And Ananda was sitting outside the hall. The doors were closed and he was weeping outside on the steps. He was weeping because he was not allowed inside. An eighty-four-year-old man weeping like a child! The man who had lived for forty-two years with Buddha was not allowed in! Now he was really in anguish. Why did he not become enlightened? Why did he not insist7 He made a vow, a decision: "I will not move from these steps until I become enlightened." He closed his eyes, he forgot the whole world. And it is said that within twenty-four hours, without changing his posture, he became enlightened.

When he became enlightened he was allowed in. Then he related... all these scriptures were related by Ananda. But who knows? He became enlightened afterwards. All those memories belong to the mind of an unenlightened person; even though he had become enlightened, those memories were not those of an enlightened person. It is not absolutely certain that what is reported is exactly what Buddha said.

But now science has given all the technology. Each single word -- not only the word but the pauses in between -- the very nuances of the words, the way they are uttered, the very gestures, all can be recorded. The words can be recorded, the gestures can be photographed, films can be made, tapes can be made.

Now the best way for any enlightened person is not to depend on anybody else, although that path is difficult, far more difficult, because you have to do two things together. You have to constantly shuttle back and forth, back and forth. You have to constantly go into wordlessness and come out from that emptiness into the world of words. It is a difficult phenomenon, the most difficult phenomenon in the whole of existence, because when you enter into silence it is so beautiful that to come back to the universe of words looks absurd, meaningless. It is as if you have reached to the sunlit peaks and then you come back to the dark holes where people live in the valley, the slums. When you have touched the sunlit peaks, when you can live there and you can float like a cloud in the infinite sky, to come back to the muddy earth, to crawl again with people who are living in mud seems to be very absurd. But there is no other way. If you have compassion enough you have to go into this difficult process.

It depends on many things too. It depends on the whole process by which a Master has reached through many lives. Ramakrishna was never an intellectual in any of his lives. A simple man -- in this life he was a simple man. Even if he had wanted to it would have been impossible for him to become a Vivekananda too. It was easier to find somebody who could do that work.

Gurdjieff, when he was very young, only twelve years of age, became part of a party of seekers: thirty people who made a decision that they would go to the different parts of the world and find out whether truth was only talk or there were a few people who had known it. Just a twelve-year-old boy, but he was chosen to join the party for the simple reason that he had great stamina, he had great power. One thing was certain about him: whatsoever he decided, he would risk all for it. He would not look back, he would never escape even if he had to lose his life he would lose his life. And three times he was almost shot dead -- almost, but he pulled himself back into life somehow; the purpose was still unfulfilled.

Those thirty people traveled all over the world. They came to India, they went to Tibet and the whole Middle East, all the Sufi monasteries, all the Himalayan monasteries. And they had decided to come back to a certain place in the Middle East and to relate whatsoever they had gained; after each twelve years they were going to meet. At the end of the first twelve years almost half of them did not return; they must have died somehow, or forgotten the mission, or become entangled somewhere. Somebody must have got married, fallen in love. A thousand and one things can happen -- people are accident-prone. Only fifteen people returned. And after the next twelve years only three people came back. And the third time only Gurdjieff was there, all the others had disappeared. What happened to them nobody knows.

But this man had very great decisiveness: if he had decided then nothing was going to deter him. He was almost killed three times; the only thing that saved him was his mission, that he had to go back, and he pulled himself out of his death. It needed great inner power.

He had no time to become an intellectual. He was moving with mystics -- from one monastery to another monastery, from one cave to another cave, from one country to another country. He came to India, he went to Tibet, he went up to Japan; he gathered knowledge from all over the world. By the time he himself became enlightened there was no time left for him to intellectualize it, to put it into words. He knew the taste, but the words were not there. He needed a man like Ouspensky.

My own approach has been totally different. I began as an intellectual -- not only in this life but in many lives. My whole work in many lives has been concerned with the intellect -- refining the intellect, sharpening the intellect. In this life I began as an atheist with an absolute denial of God. You cannot be an atheist if you are not supraintellectual, and I was an absolute atheist. People used to avoid me because I was doubting each and every thing and my doubt was contagious. Even my teachers would avoid me.

One of my teachers was dying; I went to see him. He said, "Please... I am happy that you have come, but don't say a single word because this is not the time. I am dying and I want to die believing that God is."

I said, "You cannot. Seeing me, the doubt has already arisen.'

He said, "What do you mean?"

And the thing started! Before he died, just after twelve hours, he died an atheist. And I was so happy! I had to work for twelve hours continuously. Out of desperation he said, "Okay, let me die peacefully. I say that there is no God. Are you happy? Now leave me alone!"

My university professors were always in difficulties. I was expelled from one college, then another, and then thrown out of one university. Finally one university admitted me with the condition -- I had to sign it, a written condition -- that I would not ask any questions and I would not argue with the professors.

I said okay. I signed it and the Vice-Chancellor was very happy. And I said, "Now, a few things. What do you mean by'argument'?"

He said, "Here you go!"

I said, "I have not written that I would not ask for any clarification. I can ask for a clarification. What do you mean by an'argument'? And if I cannot ask a question, what is the point of your whole department of philosophy? -- because all your philosophers ask questions. The whole of philosophy depends on doubt; doubt is the base of all philosophy. If I cannot doubt your stupid philosophers, your stupid professors, then how am I going to learn philosophy?"

He said, "Look at what you are saying! You are calling my professors, in front of me, stupid!"

I said, "They are stupid, otherwise why these conditions? Can you think of somebody being intelligent and asking his students not to question him? Is this a sign of intelligence? A professor will invite questions. An intelligent professor will be happy with a student who can argue well."

That remained a problem. My whole approach from the very beginning was not that of a Ramakrishna. I am not a devotional type, not at all. I have arrived at God through atheism, not through theism. I have arrived at God not by believing in him but by absolutely doubting him. I have come to a certainty because I have doubted and I went on doubting till there was no possibility to doubt anymore, till I came across something indubitable. That has been my process.

That was not the process of Gurdjieff. He was learning from Masters, moving from one Master to another Master, learning techniques and methods and devices. He learned many devices, but he learned in a very surrendered spirit, that of a disciple.

I have never been anybody's disciple; nobody has been my Master. In fact, nobody was ready to accept me as a disciple, because who would like to create trouble?

One of my professors, who is now dead, Dr. S.K. Saxena, loved me very much. The only man out of all my professors... because I came across many professors; I had to leave many colleges and many universities. Rarely does one come across as many professors as I came across. He is the only man that I had some respect for because he never prevented me from doubting, from questioning, even though a thousand and one times he had to accept defeat. I respected him because he was capable of accepting defeat even from a student. He would simply say, "I accept defeat. You win. I cannot argue anymore. I have put forward all the arguments that I can muster and you have destroyed them all. Now I am ready to listen to you if you have something to say."

He was very afraid.... When I was doing my final M.A. examination in philosophy he was very afraid because he loved me so much. He wanted me to get through the examination, but he was afraid -- afraid that I might write things which were not according to the textbooks or were against the textbooks. I might say things which were not acceptable to the ordinary professors. Just to save me he gave all the papers to such people all over the country as were his friends and he informed them: "Please take care of this young man, don't be offended by him; that is his way. But he has great potential."

Only one thing he could not manage, that was something to be decided by the Vice-Chancellor himself: the verbal examination, and that was the last thing. And the professor had invited a Mohammedan professor from Aligarh University, the head of the department of philosophy there, a very fanatic Mohammedan. My professor was very worried. He said to me again and again, "Don't argue with this man. In the first place, he is a Mohammedan -- Mohammedans don't know what argument is. He is very fanatical; if he cannot argue with you he will take revenge. And I know he cannot argue -- I know him, I know you. But you just remain quiet because this is the last thing. Don't destroy the whole effort that I have made for you." He said to me, "It is not your examination, it seems that I am being examined!"

I said, "I will see."

And the first question the Mohammedan professor asked was: "What is the difference between Indian philosophy and Western philosophy7"

I said, "This is something stupid. The very idea! This is nonsense. Philosophy is philosophy. How can philosophy be Indian? And how can philosophy be Eastern or Western? If science is not Eastern and science is not Western, then why philosophy? Philosophy is a quest for truth. How can the quest be Eastern or Western? The quest is the same!"

My professor started pulling my leg underneath the table. I said, "Sir, you stop! Don't pull my leg! Forget all about the examination -- now this thing has to be decided! "

The Mohammedan professor was at a loss. What was going on? He said, "What is the matter?"

I said, "He is pulling my leg. He is telling me that you are a Mohammedan -- and a fanatic Mohammedan. And he says that if you cannot argue well with me you will take revenge! So do whatsoever you want, but I have to say what I feel. I don't believe in all these distinctions. In fact, to me the very idea of somebody being a philosopher and yet a Mohammedan is simply illogical, it is ridiculous. How can you be a real inquirer if you have already accepted a certain dogma, a certain creed? If you start from a priori assumptions, if you start from a belief, you can never reach the truth. Real philosophy starts in a state of not-knowing. And that is the beauty of doubt: it destroys all beliefs."

For a moment he was shocked, felt almost dumb, but he had to give me ninety-nine marks out of a hundred. I asked him, "What happened to the last one?"

He said, "This is something! In my whole life I have never given anybody ninety-nine marks out of a hundred, and you are asking me,'What happened to the last one?' "

I said, "Yes! Since you are giving me ninety-nine I have every right to ask why you are so miserly. Just one! Make it a hundred -- at least be generous for once!"

He had to make it a hundred.

My whole approach has been a totally different approach than that of Ramakrishna and Gurdjieff. I have arrived through doubt, I have arrived through deep and profound skepticism. I have arrived not through belief but through the denial of all belief and disbelief too, because disbelief is belief in a negative form.

A moment came in my life when all beliefs and all disbeliefs disappeared and I was left utterly empty. In that emptiness the explosion happened. Hence it is not so difficult for me, so I can argue easily. I can even argue against argument; that's what I am going to continue to do. I can argue against intellect because I know how to use intellect.

Ramakrishna had never used his intellect; he started from the heart. And the same is the case with Gurdjieff. Buddha could use the intellect because he was the son of a king, well educated, well cultured. All the great philosophers of the country were called to teach him; he knew what the intellectual approach was. And then he became fed up with it.

The same happened with me. I know what can be achieved through intellectual effort: nothing can be achieved through it. When I say it I say it through my own experience.

But it has been beautiful in one way. It did not result in giving me truth -- it cannot give truth to anybody -- but in an indirect way it has cleansed the ground, it has prepared the ground. It has not helped me to realize myself, but it has helped me to communicate whatsoever I have realized.

I can communicate with you very easily, with no problems. You can ask all kinds of questions, you can ask, you can doubt, because I know that all these questions and doubts can be quashed, they can be destroyed. And it is good that you should ask because then I can destroy your questions. Once all your questions are destroyed, the answer arises in your own being. In that utter emptiness something wells up; it is already there.

I am not in favor of repressing doubt by believing. You are not here to believe in me, you are here to bring out all your disbelief. Your doubts, your questions, all are respected, welcome, so that they can be taken out from you. Slowly slowly a silence, a state of not-knowing arises. And the state of not-knowing is the state of wisdom, is the state of enlightenment.

Next: Chapter 8: The Head And The Heart, Question 2

Energy Enhancement Enlightened Texts Zen Walking in Zen, Sitting in Zen

| ENERGY

|

GAIN ENERGY APPRENTICE

LEVEL1

|

THE ENERGY BLOCKAGE REMOVAL

PROCESS

|

THE KARMA CLEARING

PROCESS APPRENTICE LEVEL3

|

MASTERY

OF RELATIONSHIPS TANTRA APPRENTICE LEVEL4

|

|

ENERGY ENHANCEMENT TESTIMONIALS EE LEVEL1 EE LEVEL2 EE LEVEL3 EE LEVEL4 EE FAQS |

|

ENERGY ENHANCEMENT TESTIMONIALS EE LEVEL1 EE LEVEL2 EE LEVEL3 EE LEVEL4 EE FAQS |