The Dresden Codex – and a short list of books you might want to study during your last week on planet Earth. The Dresden Codex also known as Codex Dresdensis, was written in the eleventh or twelfth century but is considered a copy of a Maya text several hundred years older. This makes it the oldest book written in the Americas. You will also find a public domain two-volume work by Mark Pitts explaining how to read the Maya Glyphs, a short introduction to the Maya Calender and a paper by Professor Vincent H. Malmström on the The Astronomical Insignificance of Maya Date 13.0.0.0. You might also consider consulting the Popol Vuh, The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumaye and Codex Borbonicus also known as Codex Cihuacoat

The Dresden Codex 49Mb

Maya Glyphs Book I – Names, Places, & Simple Sentences

Maya Glyphs Book II – Maya Numbers & The Maya Calendar

Mayan Calendar Explained – by Bruce Scofield

The Astronomical Insignificance of Maya Date 13

The Dresden Codex: A Window into Ancient Maya Civilization

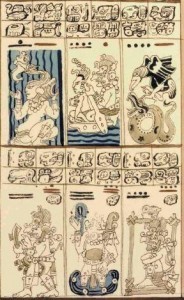

The history of the Mesoamerican world is replete with tales of powerful kings, monumental pyramids, and complex calendrical systems. But if there’s one artifact that encapsulates the brilliance and depth of the Maya civilisation, it is the Dresden Codex. Often referred to as the oldest and most comprehensive book of the Americas, the Dresden Codex offers invaluable insights into the ancient Maya’s beliefs, astronomical knowledge, and mathematical precision.

Named after the city of Dresden in Germany, where it’s currently housed in the Saxon State and University Library, the Dresden Codex is one of only four Maya books (codices) known to have survived the colonial era. Believed to be a copy of an even older text, the codex was probably written in the 11th or 12th century in the Yucatán region.

The path of the Dresden Codex to Europe remains enigmatic. It’s believed to have been sent to Europe sometime in the late 16th or early 17th century. It was only in the 18th century that it came into the possession of the Royal Library in Dresden.

Structure and Contents

The codex consists of 39 sheets, inscribed on both sides, resulting in a total of 78 pages. These pages are filled with intricate hieroglyphic texts and colorful illustrations. Made from bark paper, each sheet is coated with a thin layer of plaster, upon which the Maya scribes painted.

The contents of the Dresden Codex can be divided into various sections:

- Astronomical Tables: Perhaps the most celebrated aspect of the codex, these tables demonstrate the Maya’s sophisticated knowledge of the motions of celestial bodies. Notably, the codex contains Venus tables, which track the apparent movements of the planet Venus as the morning star and the evening star. The accuracy of these tables is astounding and testifies to the Maya’s keen observational skills.

- Ecliptic Tables: Another highlight is the series of tables dealing with lunar eclipses. These tables would have been instrumental in predicting eclipses, events which had significant ritual importance.

- Ritual Calendars: The Maya had an intricate calendrical system, and the codex provides insights into their Tzolk’in (260-day) and Haab’ (365-day) calendars.

- Almanacs and Rituals: These sections include predictions and prescriptions for various activities based on the Maya zodiac, covering topics from agriculture to childbirth.

- Flood Myth: The last pages of the codex depict a catastrophic deluge, which has been interpreted by some scholars as the Maya version of a worldwide flood myth.

Significance

The Dresden Codex is not just a testament to the Maya’s advanced knowledge in astronomy and mathematics, but it also offers a window into their worldview, religious beliefs, and daily life. Its survival is especially poignant given that many Maya books were destroyed by Spanish colonists in an attempt to eradicate indigenous beliefs.

In contemporary times, the codex is a symbol of resilience. It underscores the value of preserving ancient knowledge and stands as a witness to the profound intellectual achievements of the pre-Columbian Americas.

In Conclusion

The Dresden Codex remains one of the most significant artifacts from the ancient world. It serves as a reminder of the rich history of the Maya and the broader Mesoamerican civilizations. For researchers, historians, and enthusiasts alike, the codex continues to be a source of inspiration and wonder, offering timeless insights into one of history’s most intriguing cultures.

One image at the bottom looks Aryan-Semitic .