Buddhist cosmology

Buddhist cosmology describes a universe consisting of an inconceivable number of world-systems (lokadhātu) which come into being, exist for a while and eventually decay — in an unending cycle of creation and destruction. In each world-system there exists a multitude of different types of beings that, propelled by their own karma, cycle endlessly from one type of rebirth to another.

Generally speaking, within each world system, there are "higher realms" full of pleasant or even blissful experiences that are the result of a "favorable rebirth," and there are "lower realms" full of unpleasant and even extremely painful experiences that are the result of an "unfavorable rebirth." The human realm (or human experience) in a world-system is a mix of both pleasant and unpleasant experiences. The particular circumstances of each rebirth are determined by the karma accumulated in all of the previous lives of an individual being.

The experience of ordinary beings taking rebirth after rebirth within a world-system is referred to as "cyclic existence" (saṃsāra), a continuous wandering from one life to the next. This type of existence is described as "going round and round from one place to another in a circle, like a potter's wheel..."[1] Whether one takes rebirth into a higher realm or a lower realm, one is still trapped within the cycle, like a fly trapped in a jar.[1]

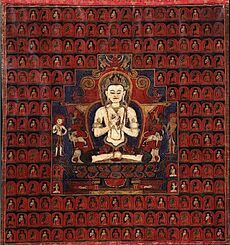

In the Buddhist view, the buddhas are those who have transcended the cycle of rebirth through developing limitless wisdom and compassion. Hence the buddhas are able to guide other beings to escape the endless cycle of birth and death.

Cosmology in relation to the core Buddhist teachings

The Buddhist view of cosmology is directly related to, and is an example of, the core Buddhist teachings on the nature of duḥkha ("suffering"), karma, impermanence, etc.

Rupert Gethin states:

- The Buddha’s teaching seeks to address the problem of duḥkha or ‘suffering’. For Buddhist thought, whatever the circumstances and conditions of existence—good or bad—they are always ultimately changeable and unreliable, and hence duḥkha. Complete understanding of the first noble truth is said to consist in the complete knowledge of the nature of duḥkha. One of the preoccupations of Buddhist theory, then, is the exhaustive analysis of all possible conditions and circumstances of existence. Buddhist thought approaches the analysis of duḥkha from two different angles, one cosmological and the other psychological. That is, it asks two different but, in the Buddhist view of things, fundamentally related questions. First, what are the possible circumstances a being can be born, exist, and die in? And second, what are the possible states of mind a being might experience? The complete Buddhist answer to these questions is classically expressed in the Abhidharma systems.[2]

Buddhist cosmology, then, addresses the first question above: what are the possible circumstances a being can be born, exist, and die in?

In his teachings, the Buddha discussed many details and principles of cosmology, and these details were systematized into a coherent whole by the Abhidharma traditions of Buddhist thought.[2]

Note that in discussions with his students, there were some questions that the Buddha refused to answer, such as "is the universe eternal?" or "is the universe not eternal?". (See the unanswered questions.) In declining to answer these questions, the Buddha said that the seeking the answers to these types of questions will not help one on the spiritual path.

The Buddha did allow, however, that the beginning of samsara was inconceivable to an ordinary person, and that its starting point could not be indicated.[2]

Textual sources

The main textual sources for Buddhist cosmology are the Abhidharma traditions of the Theravada and the Sarvāstivādin school. The Kālacakra teachings of northern India are also an important influence on the understanding of cosmology within Tibetan Buddhism.

Abhidharma traditions

Rupert Gethin states:

- The earliest strata of Buddhist writings, the Nikāyas/Āgamas, do not provide a systematic account of the Buddhist understanding of the nature of the cosmos, but they do contain many details and principles that are systematized into a coherent whole by the Abhidharma traditions of Buddhist thought. Two great Abhidharma traditions have come down to us, that of the Theravādins, which has shaped the outlook of Buddhism in Sri Lanka and South-East Asia, and that of the Sarvāstivādins, whose perspective on many points has passed into Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism. The elaborate cosmological systems detailed in these two Abhidharmas are, however, substantially the same, differing only occasionally on minor points of detail. This elaborate and detailed cosmology is thus to be regarded as forming an important and significant part of the common Buddhist heritage. Moreover, it is not to be regarded as only of quaint and historical interest; the world-view contained in this traditional cosmology still exerts considerable influence over the outlook of ordinary Buddhists in traditional Buddhist societies.[2]

Kālacakra tradition

The Kālacakra tradition is an Indian Vajrayāna tradition with extensive focus on cosmology and astronomy. This tradition has had a major influence on Tibetan Buddhist thought, particularly within the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Kālacakra system differs with Abhidharma on several points, including:

- on “the question of how the first elements of the new universe come into being.”

- on the shape or structure of the universe (lokadhātu)

- “Although Kālacakra too accepts this Meru-centric model, it differs from Abhidharma texts on the shape of Mount Meru as well as on the motion of the celestial bodies, such as the sun and moon.”[3]

Note: this article presents the traditional Abhidharma cosmology. For further information on Kalachakra cosmology, see:

Buddhist Cosmology in Abhidharma and Kalachakra, StudyBuddhism

Buddhist Cosmology in Abhidharma and Kalachakra, StudyBuddhism

Characteristics of the outer physical environment

Countless world systems

Peter Harvey states:

- The physical universe is said to consist of countless world-systems spread out through space, each seen as having a central mountain (Meru) surrounded by four continents and smaller islands, which came to be seen as all on a flat disc (e.g. Vism.205–6). They also exist in thousandfold clusters, galactic groupings of these clusters, and super-galactic groupings of these galaxies (A.I.227). Within this vast universe, with no known limit, are other inhabited worlds where beings also go through the cycle of rebirths. Just as beings go through a series of lives, so do world-systems: they develop, remain for a period, come to an end and are absent, then are followed by another. Each phase takes an ‘incalculable’ eon, and the whole cycle takes a ‘great’ eon (Harvey, 2007d: 161a–165a). The huge magnitude of this period is indicated by various suggestive images. For example, if there were a seven-mile-high mountain of solid granite, and once a century it was stroked with a piece of fine cloth, it would be worn away before a great eon would pass (S.II.181–2). Nevertheless, more eons have passed than there are grains of sand on the banks of the river Ganges (S.II.183–4)![4]

Never-ending cycle of formation and destruction

Thupten Jinpa states:

- Buddhist sources converge on the basic intuition that there is no discernable beginning of the universe. The beginningless universe is, in a way, a logical consequence of the rejection of theism, for the only other option available would be origination ex nihilo, something arising from nothing, a standpoint anathema to all Buddhists given their commitment to the law of causality. The picture we obtain of cosmology from the Buddhist sources is a never-ending cycle of universes coming into being and ending through destruction. As explained in our volume, the texts speak of in fact four phases in this cycle — formation, abiding, destruction, and emptiness. When a new universe comes into being, it is said to begin with the emergence of the wind element, followed by the water element, the fire element, and finally the earth element. To the question what sets in motion this process for the formation of a new world, the Abhidharma texts point to the power of the karma of the sentient beings that will come to inhabit that world (see page 299). This said, as in science, the Abhidharma texts also understand that the emergence of sentient beings comes long after the formation of the external world. When the time comes for the end of a world, it is said to be destroyed mostly by fire, as the sun’s power increases manifold. The Abhidharma sources speak in fact of a specific pattern in this destruction process — after every seven times destruction by fire, there will be one destruction by water, and after every seven destructions by water, there will be one destruction by wind (see pages 314–15).[3]

The four phases of existence of a world system

When a world-system arises, it remains in existence for a vast unit of time known as a mahākalpa (P. mahākappa), or "great eon."[5][6]

A mahākalpa is divided in to four periods, each describing a phase in the evolution of a world system:[6][7][8][9]

- eon of formation (vivartakalpa),

- eon of endurance (vivartasthāyikalpa),

- eon of destruction (saṃvartakalpa) and

- eon of voidness or nothingness (saṃvartasthāyikalpa or ṡūnyākalpa).

Each of the four periods consists of twenty intermediate kalpas (antarakalpa), resulting in eighty intermediate kalpas over the span of the mahākalpa.[5]

Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics (Vol 1) states:

- [In the Abhidharma system] there are the eons of destruction, voidness, formation, and endurance. The combination of these four is referred to, both in the sūtras and in the Abhidharma treatises, as a “great eon.”

- From among these, the eon of destruction is posited as beginning from when the new birth of sentient beings in Avīci hell ceases up to the termination of external world systems. The period of destruction of sentient beings who inhabit those worlds is nineteen intermediate eons, and the period of destruction of external worlds is one intermediate eon. Thus it lasts twenty intermediate eons.

- The eon of voidness is said to be the period of abiding in a void state from the destruction of former worlds up until but not including the formation of future world systems. It also lasts for twenty intermediate eons.

- The eon of formation is posited from the initial development of the wind maṇḍala as the lower foundation up to the birth of the first sentient being in the hells. The formation of external worlds takes one intermediate eon, and the evolution of their inhabitants takes nineteen intermediate eons. Thus it lasts for twenty intermediate eons.

- The eon of endurance lasts one intermediate eon in its initial phase and one intermediate eon in its final phase, plus the eighteen intermediate epochs between them. By adding each of these intermediate eons the stage lasts for twenty intermediate eons. The initial phase is the period of one intermediate eon where the lifespan decreases from an incalculable period to a lifespan of ten years.[6]

The structure of our world-system

Treasury of Precious Qualities states:

- A single [world-system] (lokadhātu), which is the impermanent environment of living beings, comprises four continents situated around a Mount Meru with its celestial abodes of the sensory domain (kāma-dhātu) and the domain of subtle form (rūpa-dhātu).[10]

Thupten Jinpa states:

- At the heart of the Abhidharma model is Mount Meru, a massive mountain whose base extends downward into the depths of a cosmic ocean and whose tips touch the abodes of the celestial beings. It is said to be surrounded by seven concentric circles of mountains and oceans, with four continents in each of the four cardinal directions, each flanked by two smaller continents.[3]

Dudjom Rinpoche states:

- In the center of the ocean is Mount Meru with its four steps. It is square in shape, with its top surface broader and opening out. Its eastern side is made of crystal, the south of lapis lazuli, the west of ruby, and the north of gold, all blazing with light, so that the ocean, sky, and continents on each side take on their respective hues. Mount Meru is surrounded by seven golden mountain ranges disposed like screens in a square around it — Yugandhara, Ishadhara, Khadiraka, Sudarshana, Ashvakarna, Vinataka, and Nimindhara — each range being half the height of the previous one.[11] These mountain ranges are separated from each other by the Seas of Enjoyment, whose waters have the eight perfect qualities described in the Vinaya scriptures:

- Cool, sweet, light, and soft,

- Clear and odorless,

- Soothing on the stomach when drunk,

- And not irritant to the throat—

- Such is water that has the eight perfect qualities.

- They are filled with wish-fulfilling jewels and the other multifarious riches that belong to the nagas.[12]

Outside of the seventh mountain range, there is a great ocean that is contained by a ring of iron mountains (cakravāda); these iron mountains form the perimeter of our world-system.[13]

The Princeton Dictionary states:

- In this vast ocean, there are four island continents in the four cardinal directions, each flanked by two island subcontinents. The northern continent is square, the eastern semicircular, the southern triangular, and the western round. Although humans inhabit all four continents, the “known world” is the southern continent, named Jambudvīpa, where the current average height is four cubits and the current life span is one hundred years.[13]

Regarding the four continents, Dudjom Rinpoche states:

- Outside the seven golden mountain ranges are the four great continents, whose colors correspond to those of the four sides of Mount Meru. In the east is Purvavideha, which is semicircular in shape. To the south is the triangular Jambudvipa. In the west is Aparagodaniya, which is round. In the north is Uttarakuru, which is square. To the right and left of each of these four continents are the eight subcontinents: Deha and Videha in the east, Chamara and Aparachamara in the south, Shatha and Uttaramantrina in the west, and Kurava and Kaurava in the north. They have the same color and shape as their respective main continents and are half their size.

- The eastern continent is full of mountains of diamonds, lapis lazuli, sapphires, emeralds, pearls, gold and silver, crystals, and other precious minerals. The southern continent is covered with a great forest of wish-fulfilling trees from which everything one could want or need falls like rain. The western continent swarms with herds of elephants and cows from whose every hair flows an inexhaustible supply of everything one could desire. The northern continent is filled with crops that need no cultivation: they yield a hundred flavors and a thousand powers, dispelling all illness, negative forces, hunger, and thirst.[12]

Characteristics of the beings that inhabit the outer environment

The threefold division of beings

The most basic division of the beings in any world-system (lokadhātu), including our own, is threefold. The threefold division (traidhātuka) consists of the following three domains/worlds/realms (dhātu):[2]

- domain of the five senses (kāma-dhātu) - is inhabited by human beings and other types of beings endowed with physical bodies and five senses. There are eleven sub-realms in the kāma-dhātu, ranging from the realms of hell and ‘the hungry ghosts’, through the realms of animals, jealous gods, and human beings, to the six realms of the lower gods.

- domain of subtle form (rūpa-dhātu) - is inhabited by refined beings who have subtle physical form (bodies) and only two senses: sight and smell. The rūpa-dhātu has sixteen sub-realms occupied by various higher gods (devas) collectively known as Brahmās.

- the formless domain (arūpa-dātu) - is inhabited by beings of pure consciousness who have no physical form (bodies). The arūpa-dātu has four sub-realms occupied by a further class of Brahmās who have only consciousness.

These three domains and their sub realms, when viewed from bottom to top, thus reflect a basic movement from gross to subtle.[2]

These three realms are commonly divided into further sub-divisions; the total number of sub-divisions is between 31 and 33 sub-realms, depending upon the tradition. The Theravada tradition counts 31 sub-realms in total,[14] and the Sanskrit traditions count 32 or 33.[15]

The following table shows the list of thirty-two sub-realms commonly identified in the Sanskrit tradition.[15] The sub-realms are listed from highest (most subtle) to lowest (most gross).

| Domains (dhātu) | Divisions/levels (bhūmi) |

|---|---|

| formless domain (arūpadhātu) - beings have consciousness, but no physical form (bodies) |

|

| domain of subtle form (rūpadhātu) - beings have a physical form (bodies) and two senses: sight and hearing |

|

| domain of the five senses (kāmadhātu) - beings have physical bodies and all five senses |

According to the cosmology of the Abhidharma, beings within cyclic existence (saṃsāra) can take rebirth into any of the thirty-two sub-realms,[17] or situations, shown in the table above.

Rupert Gethin states:

- Indeed, one should rather say that every being has during the course of his or her wandering through saṃsāra at some time or another been born in every one of these conditions apart, that is, from five realms known as ‘the Pure Abodes’; beings born in these realms ... have reached a condition in which they inevitably attain nirvāṇa and so escape the round of rebirth.[2]

Kāmadhātu (domain of the five senses)

Kāmadhātu is translated as "domain of the five senses," "sensuous realm," "desire realm," etc. The beings in this realm are endowed with physical bodies and all five senses.[2]

This realm is characterized "as principally dependent on external objects of sensual desire such as form, sound, and so on."[18] If explained further by means of body, feelings, and resources: "the body is coarse, experience is predominantly a mixture of pleasure and pain, and beings depend mainly on coarse food."[18]

Among the six classes of beings in the three realms, all types of beings except the devas of the rupadhatu and arupadhatu live in the "sensuous domain/realm" (kāmadhātu).

Hence, the following classes of beings are found in this realm:

- devas of the kāmadhātu (of which there are six classes)

- jealous gods (asura)

- humans (manuṣya)

- animals (tiryak)

- hungry ghosts (preta)

- hell beings (nāraka)

These beings are said to live within 36 abodes or regions.

The thirty-six abodes are:[19]

- the six deva realms of the kāmadhātu

- the twelve abodes of human beings (i.e., the four continents and eight subcontinents)

- the abodes of animals

- the abode of pretas

- the sixteen hells.

When asuras are counted separately (from the devas), there are thirty-seven abodes.[19] Some powerful nagas are also included within the gods, but generally they are defined as animals.[20]

Rūpadhātu (domain of subtle form)

Rūpadhātu is translated as "form realm," "realm of fine materiality," "realm of subtle materiality," etc.

The beings in this realm have subtle physical form (bodies) and only two senses: sight and smell.[2]

This realm is characterized by the internal bliss of absorption.[18] If explained further by means of body, feelings, and resources: "beings there have bodies in the nature of light, their experience is permeated mostly by feelings of bliss, and they do not rely on coarse food."[18] The beings who live in this realm are considered to be celestial beings.[18]

This realm is divided into four sub-realms, which are further divided into additional sub-realms or heavens. In the Sanskrit tradition, there are seventeen heavens in total; in the Pali tradition there is one less heaven, for a total of sixteen heavens.

The cause for being reborn in one of these heavens is the favourable karma accumulated through the practice of one of the dhyanas, each 'causal meditative dhyana' acting as a cause of rebirth in one of the corresponding 'resultant dhyana levels'.[21]

Arūpadhātu (formless domain)

Arūpadhātu is translated as "formless realm', etc.

The beings in this realm have consciousness but no physical form (bodies) and no physical senses.[2]

This realm is characterized by "being disenchanted even by the bliss of absorption, on tranquility permeated by the feeling of equanimity alone."[18] If explained further by means of body, feelings, and resources: "beings there do not possess a coarse physical body that symbolizes their nature as sentient beings, they abide with feelings of equanimity transcending feelings of pain and pleasure, and they do not depend on coarse food but live their entire life in meditative concentration focused solely on objects such as limitless space, which resemble the cessation of all mental engagement in other objects."[18]

Historical and cultural context

Namkhai Norbu states:

- Every kind of teaching is transmitted through the culture and knowledge of human beings. But it is important not to confuse any culture or tradition with the teachings themselves, because the essence of the teachings is knowledge of the nature of the individual. Any given culture can be of great value because it is the means which enables people to receive the message of a teaching, but it is not the teaching itself. Let's take the example of Buddhism. Buddha lived in India, and to transmit his knowledge he didn't create a new form of culture, but used the culture of the Indian people of his time as the basis for communication. In the Abhidharma-kosa, for example, we find concepts and notions, such as the description of Mount Meru and the four continents, which are typical of the ancient culture of India, and which should not be considered of fundamental importance to an understanding of the Buddha's teaching itself.[22]

Ken Holmes states:

- The Buddha said this world is like a dream or a conjuration. Therefore, to be comprehensible, his teachings must necessarily express themselves in a way which makes sense in each person's dream. Thus much of popular early Buddhism was taught using the Indo-European world view widespread at the time, in which, living atop the highest peak and ruling other deities was a sky god, known as Dyaus by the Indians, as Zeus by the Greeks and later as Jupiter (Dies Pater) by the Romans. Such concepts had probably spread from the Asiatic steppe, westwards to Greece and eastwards to India, with the invading Aryans, some time in the second millennium BCE. The sacred mountain was Olympus for some, Sumeru for others. Upon it, wielding a thunderbolt, the Lord of Heaven controlled the weather and repulsed attacks from demi-gods.

- This early belief became extended to consider our world no longer as unique but as just one of a group of a billion similar world systems, each based around its own central, four-sided mountain, each face of which was made of a differently-coloured precious substance. Indians thought of their land, Jambudvipa, as being a trapezoidal continent to the south of the sacred mountain, opposite its lapis lazuli slope. To either side of it lay small sub-continents of similar shape. Other continents, flanked by sub-continents, lay opposite the other faces of Mt Sumeru: a semi-circular one to the east, opposite the crystal slope, a round one to the west, opposite the ruby slope and a square one to the north, opposite the emerald slope. In invisible worlds high above the summit of Mt. Meru, one above another, were the realms of the various classes of gods whereas in recesses far beneath the earth were the hells and lower abodes.

- How relatively true were these primitive ideas was of secondary importance for Buddhists. What mattered was the fact that they were deeply ingrained in the psychology of millions of beings. If teachings based upon such a world view could enable someone to acquire the tools of meditation and clear analytical inspection, what matter? The true nature of reality would eventually become apparent through vivid first-hand knowledge, above and beyond all inherited conventional beliefs. Thus no ethical problem was seen in mobilising the myths and illusions of the day, as long as they set people on the path to wisdom.

- On its deeper levels, Buddhism throws a bright light on the subjectivity of all experience. It reveals, with great pragmatism, the impossibility of establishing any ultimate objective reality and explains, as a consequence, that there are as many subjective worlds as there are sentient beings. Each moves through life in a completely unique universe fashioned by his, her or its preconceptions, due to karma. It is as though we live in parallel dreams. Furthermore, as one's awareness and mental clarity develops, many subconscious mental barriers fall away. In the newfound purity, the world around manifests to the senses very differently: there is 'a new heaven and a new earth'.

- Surrounding Mount Sumeru are seven ranges of golden mountains, each separated by lakes of pure water of eight special attributes. These are reputed to be rich in precious gems, belonging to the serpentine naga spirits who inhabit them. Mount Sumeru has four large steps at its base and is unusual insofar as it tapers outwards to a flat, square summit rather than inwards to a peak. On the summit is the palace of Indra (who replaced Dyaus), Lord of the Heavens, surrounded by gardens and wonders. In space above, the sun and moon are themselves celestial palaces, as are the stars. Then, in layer after layer, one above another and interspersed with rainbow-hued celestial clouds, are first the seventeen realms of the form gods and above them the four realms of the formless gods.

- The doctrine of karma explains the world around us to be the product of past actions, both personal and collective. The Kalachakra teachings describe cycles and tides of time, as humanity's karma carries it from age to age. Some ages - the results of much common goodness - are prosperous and peaceful with bountiful, healthy crops and longevity. Other darker ages - brought about by much evil - are riddled with disease, dishonesty, danger and a poisoned environment in which the lifespan is short. Unusual karmas produce unusual results and some worlds are said to be totally different from anything we could ever imagine. Furthermore, the tantras makes it clear that world views change as the centuries roll by. Within an endless series of parallel universes, we migrate from one to another much like actors appearing first on one television channel, then another, in quite different realities.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Patrul Rinpoche 1998, p. 61.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Gethin 1998, s.v. Chapter 5. The Buddhist Cosmos: The Thrice-Thousandfold World.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Thupten Jinpa 2017, s.v. Part 5. The Cosmos and its Inhabitants.

- ↑ Harvey 2013, s.v. Chapter 2.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. mahākalpa.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Thupten Jinpa 2017, s.v. Chapter 25: Measurement and Enumeration.

- ↑ Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. kalpa.

- ↑

བསྐལ་པ་ཆེན་པོ་བཞི་, Christian-Steinert Dictionary

བསྐལ་པ་ཆེན་པོ་བཞི་, Christian-Steinert Dictionary

- ↑ Jigme Lingpa & Kangyur Rinpoche 2010, Appendix I.

- ↑ Jigme Lingpa & Kangyur Rinpoche 2010, Chapter 2.

- ↑ "The first range of mountains, Yugandhara, is a quarter of the height of Mount Meru."

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dudjom Rinpoche 2011, s.v. Chapter 12.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. Sumeru, Mount.

- ↑ See

The Thirty-one Planes of Existence , Access to Insight

The Thirty-one Planes of Existence , Access to Insight

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dalai Lama & Thubten Chodron 2018b, s.v. Chapter 2.

- ↑ Note: the Theravada tradition counts two sub-divisions within the heavens of ordinary beings.

- ↑ Or thirty-one sub-realms according to the Theravada abhidhamma tradition.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 Thupten Jinpa 2017, s.v. "The Formation of World Systems".

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Mipham Rinpoche 2000, s.v. Line 8.17.

- ↑ Mipham Rinpoche 2000, s.v. Line 8.18.

- ↑

Form realm, Rigpa Shedra Wiki

Form realm, Rigpa Shedra Wiki

- ↑ Chogyal Namkhai Norbu 1996, chapter 1.

- ↑ Holmes, Ken. Buddhist Cosmology, Kagyu Samye Ling

Sources

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University Chogyal Namkhai Norbu (1996), Clemente, Adriano, ed., Dzogchen: The Self-Perfected State, Snow Lion Publications

Chogyal Namkhai Norbu (1996), Clemente, Adriano, ed., Dzogchen: The Self-Perfected State, Snow Lion Publications Dalai Lama; Thubten Chodron (2018b), Saṃsāra, Nirvāṇa, and Buddha Nature, The Library of Wisdom and Compassion, Volume 3, Wisdom Publications

Dalai Lama; Thubten Chodron (2018b), Saṃsāra, Nirvāṇa, and Buddha Nature, The Library of Wisdom and Compassion, Volume 3, Wisdom Publications Dudjom Rinpoche (2011), A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom: Complete Instructions on the Preliminary Practices, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Shambhala

Dudjom Rinpoche (2011), A Torch Lighting the Way to Freedom: Complete Instructions on the Preliminary Practices, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Shambhala Gethin, Rupert (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press

Gethin, Rupert (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press Harvey, Peter (2013), An Introduction to Buddhism (Second ed.), Cambridge University Press

Harvey, Peter (2013), An Introduction to Buddhism (Second ed.), Cambridge University Press Jigme Lingpa; Kangyur Rinpoche (2010), Treasury of Precious Qualities, Book One, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Boston: Shambhala Publications

Jigme Lingpa; Kangyur Rinpoche (2010), Treasury of Precious Qualities, Book One, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Boston: Shambhala Publications Mipham Rinpoche (2000), Gateway to Knowledge, vol. II, translated by Kunsang, Erik Pema, Rangjung Yeshe Publications

Mipham Rinpoche (2000), Gateway to Knowledge, vol. II, translated by Kunsang, Erik Pema, Rangjung Yeshe Publications Patrul Rinpoche (1998), Words of My Perfect Teacher, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Altamira Press

Patrul Rinpoche (1998), Words of My Perfect Teacher, translated by Padmakara Translation Group, Altamira Press Thupten Jinpa, ed. (2017), Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics, Volume 1: The Physical World, translated by Coghlan, Ian James, Wisdom Publications

Thupten Jinpa, ed. (2017), Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics, Volume 1: The Physical World, translated by Coghlan, Ian James, Wisdom Publications

Further reading

- "Cosmology: Buddhist Cosmology." Encyclopedia of Religion. Encyclopedia.com. 22 Aug. 2023

- Buddhist Cosmology, Oxford Research Encyclopedia. 28 Jan. 2022

- Burley, Mikel. “Conundrums of Buddhist Cosmology and Psychology.” Numen 64, no. 4 (2017): 343–70.

- Holmes, Ken. Buddhist Cosmology, Kagyu Samye Ling

- Wallace, Vesna. Cosmology, Astronomy and Astrology, Oxford Bibliographies. 13 Sep. 2010

- Buddhist rebirth in different planes of existence, British Library

- Jayatilleke, K.N. "Facets of Buddhist Thought". Buddhist Publication Society. Buddhist Publication Society. Retrieved 9 Mar 2024.

- Manual of Buddhist Cosmology, Namse Bangdzo Bookstore

- Buddhist Cosmology, Encyclopedia Buddhica