Five skandhas

Five skandhas (S. pañca skandha; P. pañca khandha; T. phung po lnga, ཕུང་པོ་ལྔ་), or five heaps or five aggregates, are five psycho-physical aggregates, which according to Buddhist philosophy are the basis for self-grasping. They are:

- rupa-skandha - aggregate of form

- vedana-skandha - aggregate of sensations

- saṃjñā-skandha - aggregate of recognition, labels or ideas

- saṃskāra-skandha - aggregate of volitional formations (desires, wishes and tendencies)

- vijñāna-skandha - aggregate of consciousness

The five skandhas are essentially a method for understanding that every aspect of our lives is a collection of constantly changing experiences. There is no one aspect that is truly solid, permanent or unique. Everything is in flux. Everything is dependent upon multiple causes and conditions.

For example, rupa-skandha refers to everything in our material world–our body and our physical surroundings. All these things are constantly changing. Vedana-skandha refers to our sensations that are positive, negative or indifferent–all our sensations are fleeting, changing from moment to moment. Samjna-skandha refers to all of our recognition or labeling of everything that we see, hear, smell, touch, or think; these labels are also constantly in flux. Samskara-skanda (all of our mental habits, thoughts, ideas, opinions, prejudices, compulsions, etc.) are dependent on many causes and conditions and always changing. Our consciousness itself is not one single thing, but a collection of consciousness (vijnana-skandha) that are also constantly changing.

In the Buddhist view, by contemplating on the characteristics of the skandhas, we can overcome self-grasping. Self-grasping is attachment to the concept of a self that is unique, independent and permanent. In the Buddhist view, it is this attachment to this distorted view of the self that is the root cause of suffering. Therefore, by letting go of this attachment, we can liberate ourselves from suffering.

Etymology

The Sanskrit word skandha (P. khandha; T. phung po ཕུང་པོ་; C. yun 蘊) can mean mass, heap, pile, gathering, bundle or tree trunk.[1]

Thanissaro Bhikkhu states:

- Prior to the Buddha, the Pali word khandha had very ordinary meanings: A khandha could be a pile, a bundle, a heap, a mass. It could also be the trunk of a tree. In his first sermon, though, the Buddha gave it a new, psychological meaning, introducing the term clinging-khandhas to summarize his analysis of the truth of stress and suffering. Throughout the remainder of his teaching career, he referred to these psychological khandhas time and again.[2]

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism states:

- In Sanskrit, lit. “heap,” viz., “aggregate,” or “aggregate of being”; one of the most common categories in Buddhist literature for enumerating the constituents of the person. According to one account, the Buddha used a grain of rice to represent each of the many constituents, resulting in five piles or heaps.[3]

Characteristics

Aggregates, heaps, etc.

Each of the five skandhas is a collection of things. For example, the skandha of form consists of everything in the material world. The skandha of feeling consists of feelings that are pleasant, unpleasant, and neither pleasant nor unpleasant. And so on.

...each aggregate is a collection of many components. The components of one aggregate may be different types of phenomena, such as love and anger, or they may be different possibilities of one phenomenon, such as the feeling of different levels of happiness. When part of experience, each variable component changes from moment to moment and has a different length of continuity.[4]

Constantly changing

Each of the five skandhas are impermanent; they are constantly changing, constantly in flux. They are never the same from one moment to the next. Contemporary scholars Smith and Novak write:

To underscore life’s fleetingness the Buddha called the components of the human self skandhas—skeins that hang together as loosely as yarn—and the body a “heap,” its elements no more solidly assembled than grains in a sandpile. But why did the Buddha belabor a point that may seem obvious? Because, he believed, we are freed from the pain of clutching for permanence only if the acceptance of continual change is driven into our very marrow. Followers of the Buddha know well his advice:

- Regard this phantom world

- As a star at dawn, a bubble in a stream,

- A flash of lightning in a summer cloud,

- A flickering lamp—a phantom and a dream.

- - Diamond Sutra, v 32.[5]

Contemporary scholar Peter Harvey writes:

Buddhism emphasizes that change and impermanence are fundamental features of everything, bar Nirvana. Mountains wear down, material goods wear out or are lost or stolen, and all beings, even gods, age and die (M.II. 65– 82 (BW. 207– 13); EB. 3.2.1). The gross form of the body changes relatively slowly, but the matter which composes it is replaced as one eats, excretes and sheds skin cells. As regards the mind, character patterns may be relatively persistent, but feelings, moods, ideas, etc. can be observed to constantly change. The ephemeral and deceptive nature of the khandhas is expressed in a passage which says that they are ‘devoid, hollow’ as:

- Material form is like a lump of foam,

- and feeling is like a bubble;

- perception is like a mirage,

- and the constructing activities are like a banana tree [lacking a core, like an onion];

- consciousness is like a [magician’s] illusion. (S.III. 142 (BW. 343– 5); SB. 220– 2).[6]

No essence

The skandhas or aggregates don't constitute any 'essence'. In the Connected Discourses, the Buddha explains this by using the simile of a chariot:

A 'chariot' exists on the basis of the aggregation of parts, even so the concept of 'being' exists when the five aggregates are available.[7][lower-alpha 1]

Just as the concept of "chariot" is a reification, so too is the concept of "self". The constituents of the "self" are unsubstantial in that they are causally produced, just like the chariot as a whole.[8]

According to Thanissaro Bhikkhu, the chariot metaphor is not an exercise in ontology, but rather a caution against ontological theorizing and conceptual realism.[9]

Clinging to the skandhas leads suffering

Clinging to the skandhas (Sanskrit; Pali: khandhas) leads to suffering. For example, Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2002) explains:

- The [discourses] depict the Buddha as saying that he taught only two topics: suffering and the end of suffering.[10] A survey of the Pali discourses shows him using the concept of the khandhas to answer the primary questions related to those topics: What is suffering? How is it caused? What can be done to bring those causes to an end?

The skadhas are not understood as an absolute truth about ultimate reality or as a map of the mind, but instead as method for understanding the causes of suffering, and how to find a way out of suffering.

Understanding leads to liberation

In the Buddhist view, by contemplating on the characteristics of the skandhas, and coming to understand that the skandhas, and thus all of our life experiences, are constantly changing and dependent on multiple causes and conditions, we can overcome our attachment to our concept of self. In the Buddhist view, it is this attachment to self that is the root cause of suffering. Therefore, by letting go of this attachment, we can liberate ourselves from suffering.

Through mindfulness contemplation, one sees an "aggregate as an aggregate" — sees it arising and dissipating. Such clear seeing creates a space between the aggregate and clinging, a space that will prevent or enervate the arising and propagation of clinging, thereby diminishing future suffering.[lower-alpha 2] As clinging disappears, so too notions of a separate "self."

The skandhas individually

Rupa-skandha

Rupa-skandha (P. rupa-khanda; T. གཟུགས་ཀྱི་ཕུང་པོ་) refers to the heap or aggregate of rupa (forms).

StudyBuddhism describes rupa-skandha as follows:

- The network of all instances of all types of sights, sounds, smells, tastes, physical sensations, physical sensors, and forms of physical phenomena included only among the cognitive stimulators that are all phenomena. Any of these can be part of any moment of experience on someone's mental continuum.[11]

Rupa is typically translated as "form", and it refers to external and internal matter. Externally, rupa is the physical world. Internally, rupa includes the material body and the physical sense organs.[lower-alpha 3]

Vedana-skandha

Vedana-skandha (P. vedana-khanda; T. ཚོར་བ་ཀྱི་ཕུང་པོ་) refers to the heap or aggregate of vedana (sensations).

StudyBuddhism describes vedana-skandha as:

- The network of all instances of the [mental factor of vedana] that could be part of any moment of experience on someone's mental continuum.[12]

In general, vedanā refers to the pleasant, unpleasant and neutral (niether pleasant nor unpleasant) sensations that occur when our internal sense organs come into contact with external sense objects and the associated consciousness.

Generally, vedanā is considered to not include "emotions." For example, Bodhi (2000a), p. 80, writes:

- The Pali word vedanā does not signify emotion (which appears to be a complex phenomenon involving a variety of concomitant mental factors), but the bare affective quality of an experience, which may be either pleasant, painful or neutral.

The factor vedana is typically translated as either "sensation" or "feelings".

Samjna-skandha

Samjna-skandha (P. sañña-khanda; T. འདུ་ཤེས་ཀྱི་ཕུང་པོ་) refers to the heap or aggregate of samjna (perceptions).

Samjna is typically translated as "perception" or "cognition." Alternate translations include: "conception," "apperception" and "discrimination".

Samjna can be defined as grasping at the distinguishing features or characteristics.[13][14]

It is also said that samjna registers whether an object is recognized or not (for instance, the sound of a bell or the shape of a tree).

StudyBuddhism describes samjna-skandha as follows:

- The network of all instances of the [mental factor of samjna] that could be part of any moment of experience on someone's mental continuum. Some translators render the term as "aggregate of recognition."[15]

Samskara-skandha

Samskara-skandha (P. saṅkhāra-khanda; T. འདུ་བྱེད་ཀྱི་ཕུང་པོ་) refers to the heap or aggregate of samskara (mental formations).

Samskara means 'that which has been put together' and 'that which puts together'.

The term samskara has been translated as "mental formations", "impulses", "volition", or "compositional factors".

Samskara has been described as all types of mental habits, thoughts, ideas, opinions, prejudices, compulsions, and decisions triggered by an object.[lower-alpha 4]

StudyBuddhism describes samskara-skandha as follows:

- The network of all instances of [mental factors other than vedana and samjna], as well as all instances of noncongruent affecting variables, that could be part of any moment of experience on someone's mental continuum. Some translators render the term as "aggregate of volitions" or "aggregate of karmic formations."[16]

Vijnana-skandha

Vijnana-skandha (P. viññāṇa-khanda; T. རྣམ་ཤེས་ཀྱི་ཕུང་པོ་) refers to the heap or aggregate of vijnana (consciousness).[17]

There are six types of vijnana (consciousness) within vijnana-skandha:

- eye consciousness (cakṣurvijñāna)

- ear consciousness (śrotravijñāna)

- nose consciousness (ghrāṇavijñāna)

- tounge consciousness (jihvāvijñāna)

- body consciousness (kāyavijñāna)

- mind consciousness (manovijñāna)

Alexander Berzin states:

Most Western cognitive theories discuss consciousness as a single factor that can cognize all categories of cognitive objects – sights, sounds, smells, tastes, physical sensations, and purely mental objects such as when thinking. In contrast, the scheme of five [skandhas] specifies different types of...consciousness in terms of the cognitive sensor it relies on to arise.

[Vijnana] cognizes merely the essential nature (ngo-bo) or type of phenomenon that something is. For example, eye consciousness cognizes a sight as merely a sight.[18]

StudyBuddhism describes vijnana-skandha as follows:

The network of all instances of mental consciousness or of any of the five types of sensory consciousness that could be part of any moment of experience on someone's mental continuum. It also includes the network of all instances of deluded awareness and all-encompassing foundation consciousness in those systems that assert these two. Also called: "aggregate of consciousness."[19]

Nina van Gorkom states:

Vinnana-kkhandha (citta) is real; we can experience it when there is seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, receiving impressions through the body-sense or thinking. Vinnana-kkhandha arises and falls away; it is impermanent.[20]

Relation to other modes of analysis

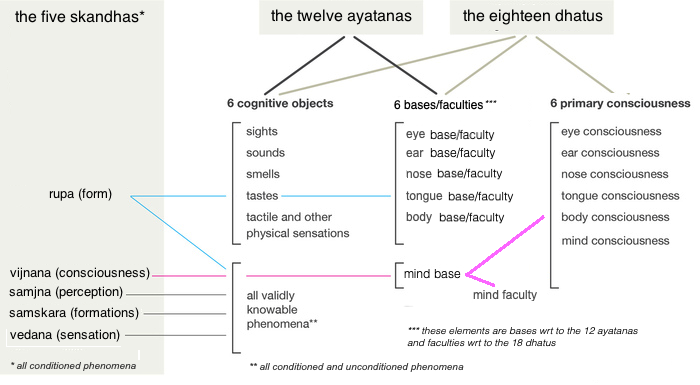

The abhidharma tradition presents multiple modes with which to analyze the components of an individual and their relationship to the world. The three most common methods of investigation are:

- five skandhas (aggregates, heaps, etc.)

- twelve ayatanas

- eighteen dhatus (sources, etc)

The following diagram shows the overlapping relationships between these modes of analysis:

Twelve ayatanas (sense bases)

The teaching of the twelve ayatanas (sense bases) provides an alternative to the five aggregates as a description of the workings of the mind.[21] In this teaching, the coming together of an object and a sense-organ results in the arising of the corresponding consciousness.

Bhikkhu Bodhi emphasizes that the suttas themselves don't describe this alternative. It is in the Abhidhamma, striving to "a single all-inclusive system"[22] that the five aggregates and the twelve (or six) sense bases are explicitly connected.[22]

The twelve sense bases are related to the five skandhas as follows:

- The first five external sense bases (visible form, sound, smell, taste and touch) are part of the form aggregate.

- The mental sense object (that is, mental objects) overlap the first four aggregates (form, feeling, perception and formation).

- The first five internal sense bases (eye, ear, nose, tongue and body) are also part of the form aggregate.

- The mental sense organ (mind) is comparable to the aggregate of consciousness.

According to the Pali tradition, the benefit of meditating on the aggregates is overcoming wrong views of the self (since the self is typically identified with one or more of the aggregates), the benefit of meditation on the six sense bases is to overcome craving (through restraint and insight into sense objects that lead to contact, feeling and subsequent craving).[23][24][25][lower-alpha 5]

Eighteen dhatus

The eighteen dhātus presented in the Abhidharma teachings are another method for understanding the components of the mind or indivual. The eighteen dhātus can be understood as acting along six channels, where each channel is composed of a sense object, a sense organ, and sense consciousness. In regards to the aggregates:[26]

- The first five sense organs (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body) are derivates of form.

- The sixth sense organ (mind) is part of consciousness.

- The first five sense objects (visible forms, sound, smell, taste, touch) are also derivatives of form.

- The sixth sense object (mental object) includes form, feeling, perception and mental formations.

- The six sense consciousness are the basis for consciousness.

Within the sutras

Within the first discourse

In the first discourse of the Buddha (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta), the Buddha presents the first noble truth as follows:

The Noble Truth of Suffering [dukkha], monks, is this: Birth is suffering, aging is suffering, sickness is suffering, death is suffering, association with the unpleasant is suffering, dissociation from the pleasant is suffering, not to receive what one desires is suffering—in brief the five aggregates subject to grasping are suffering.[27]

Bhikkhu Bodhi (2000b, p. 840) states that an examination of the aggregates has a "critical role" in the Buddha's teaching for several reasons, including:

- Understanding suffering: the five aggregates are the "ultimate referent" in the Buddha's elaboration on dukkha (suffering) in his First Noble Truth: "Since all four truths revolve around suffering, understanding the aggregates is essential for understanding the Four Noble Truths as a whole."

- Clinging causes future suffering: the five aggregates are the substrata for clinging and thus "contribute to the causal origination of future suffering".

- Release from samsara: clinging to the five aggregates must be removed in order to achieve release from samsara.

Within Pali discourses

Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2002) explains:

- The [discourses] depict the Buddha as saying that he taught only two topics: suffering and the end of suffering.[28] A survey of the Pali discourses shows him using the concept of the khandhas to answer the primary questions related to those topics: What is suffering? How is it caused? What can be done to bring those causes to an end?

Bhikkhu Bodhi (2000b, p. 840) states:

- The analysis into the aggregates undertaken in the Nikayas is not pursued with the aim of reaching an objective, scientific understanding of the human being along the lines pursued by physiology and psychology.... For the Buddha, investigation into the nature of personal existence always remains subordinate to the liberative thrust of the Dhamma....

Thus, Buddhist practitioners do not see the notion of the aggregates as providing an absolute truth about ultimate reality or as a map of the mind, but instead as providing a tool for understanding how our method of apprehending sensory experiences and the self can lead to either our own suffering or to our own liberation.

Understanding in the Sanskrit Mahayana tradition

Prajnaparamita

The Prajnaparamita teachings emphasize the "empty" nature of phenomena. This means that there are no eternally existing "essences", since everything is dependently originated. Thus, the skandhas too are dependently originated, and lack any substantial existence.

This is expressed in the Heart Sutra as follows:

At that time, the Blessed One entered the samadhi classified as the dharma called "profound illumination," and at the same time, noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, while practicing the profound prajnaparamita, saw in this way: he saw the five skandhas to be empty of nature.

Then, through the power of the Buddha, venerable Shariputra said to noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, "How should a son or daughter of noble family train, who wishes to practice the profound prajnaparamita?"

Addressed in this way, noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, said to venerable Shariputra,

"O Shariputra, a son or daughter of noble family who wishes to practice the profound prajnaparamita should see in this way: see the five skandhas to be empty of nature.

Form is emptiness; emptiness also is form.

Emptiness is no other than form; form is no other than emptiness.

In the same way, feeling, perception, formation, and consciousness are emptiness.

Thus, Shariputra, all dharmas are emptiness...[29]

Yogacara

The Yogacara-school further analysed the workings of the mind, and developed the notion of the Eight Consciousnesses. These are an elaboration of the concept of nama-rupa and the five skandhas, adding detailed analyses of the workings of the mind.

Tathagata

A tathāgata has abandoned that clinging to the personality factors that render the mind a bounded, measurable entity, and is instead "freed from being reckoned by" all or any of them, even in life. The skandhas have been seen to be a burden, and an enlightened individual is one with "burden dropped".[30]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The passage is found at S 1.135, and also in the agamas.

- ↑ That meditation creates a space between the aggregates (including clinging) is a readily accessible meditation experience. For a published authoritative statement regarding this experience, see, for example, Trungpa (2001), pp. 85-86, where in response to a student's query he replies: "By meditating you are slowing down the process. When it has slowed down, the skandhas are no longer pushed against one another. There is space there, already there."

- ↑ External and internal manifestations of rupa are described, for instance, in Bodhi (2000b), p. 48.

- ↑ The Theravada Abhidhamma divides saṅkhāra into fifty mental factors (Bodhi, 2000a, p. 26). The Sarvastivada Abhidharma studied in Mahayana Buddhism states that there are fifty-one "general types" of samskara.

- ↑ Bodhi conceptuatlizes the six sense bases as providing a "vertical" view of experience while the aggregates provide a "horizontal" (temporal) view (e.g., see Bodhi, 2000b, pp. 1122-23).

References

- ↑ Thanissaro (2002)

- ↑ Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Five Piles of Bricks: The Khandas as Burden and Path. Access to Insight. 2002.

- ↑

Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. skandha

Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. skandha

- ↑

Basic scheme of the five aggregates, StudyBuddhism

Basic scheme of the five aggregates, StudyBuddhism

- ↑ Smith, Huston; Novak, Philip (2009-03-17). Buddhism: A Concise Introduction (p. 57). HarperOne. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Harvey, Peter (2012-11-30). An Introduction to Buddhism (Introduction to Religion) (pp. 57-58). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ Kalupahana (1975), page 78

- ↑ Kalupahana (1975), page 78.

- ↑ Thanissaro Bhikkhu, [1].

- ↑ SN 22.86

- ↑

rupa-skanda, StudyBuddhism

rupa-skanda, StudyBuddhism

- ↑

vedana-skanda, StudyBuddhism

vedana-skanda, StudyBuddhism

- ↑ Kunsang 2004, p. 22.

- ↑ Guenther 1975, Kindle Locations 364-365.

- ↑

samjna-skandha, StudyBuddhism

samjna-skandha, StudyBuddhism

- ↑

samskara-skandha, StudyBuddhism

samskara-skandha, StudyBuddhism

- ↑ Vijnana (Sanskrit: vijñāna; Pali: viññāṇa) has been translated as "consciousness," "life force," "discernment" (Peter Harvey, The Selfless Mind), and so on.

- ↑

Basic Scheme of the Five Aggregates, StudyBuddhism

Basic Scheme of the Five Aggregates, StudyBuddhism

- ↑

vijnana-skandha, StudyBuddhism

vijnana-skandha, StudyBuddhism

- ↑ Nina Von Gormkom, The Five Khandhas

- ↑ Bodhi 2000b, p. 1122.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bodhi 2000b, p. 1123.

- ↑ Trungpa Rinpoche 1976

- ↑ Bodhi (2000b), pp. 1125-26

- ↑ Bodhi (2005b)

- ↑ Bodhi (2000a), pp. 287-8.

- ↑ Piyadassi Thera, trans. Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta ("The Setting in Motion the Wheel of Truth Discourse", Samyutta Nikaya 56:11). Access to Insight. 1999.

- ↑ SN 22.86

- ↑ From the translation by the Nalanda Translation Committee

- ↑ Peter Harvey, The Selfless Mind. Curzon Press 1995, page 229.

Sources

Sutta-pitaka

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (trans.) (2000b), The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya, Boston: Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-331-1

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.) (2005a). In the Buddha's Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pāli Canon. Boston: Wisdom Pubs. ISBN 0-86171-491-1.

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikkhu (trans.) & Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.) (2001). The Middle-Length Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Majjhima Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-072-X.

Abhidhamma, Pali commentaries, modern Theravada

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (ed.) (2000a). A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma: The Abhidhammattha Sangaha of Ācariya Anuruddha. Seattle, WA: BPS Pariyatti Editions. ISBN 1-928706-02-9.

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu (18 Jan 2005b). MN 10: Satipatthana Sutta (continued) Ninth dharma talk on the Satipatthana Sutta (MP3 audio file).

- Buddhaghosa, Bhadantācariya (trans. from Pāli by Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli) (1999). The Path of Purification: Visuddhimagga. Seattle, WA: BPS Pariyatti Editions. ISBN 1-928706-00-2.

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikkhu (trans.) (1998). Mindfulness of Breathing (Ānāpānasati): Buddhist texts from the Pāli Canon and Extracts from the Pāli Commentaries. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 955-24-0167-4.

- Soma Thera (trans.) (2003). The Way of Mindfulness. Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 955-24-0256-5.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2002). Five Piles of Bricks: The Khandhas as Burden & Path.

Other

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University- Guenther, Herbert V. & Leslie S. Kawamura (1975), Mind in Buddhist Psychology: A Translation of Ye-shes rgyal-mtshan's "The Necklace of Clear Understanding" Dharma Publishing. Kindle Edition.

- Kunsang, Erik Pema (translator) (2004). Gateway to Knowledge, Vol. 1. North Atlantic Books.

Cetasikas by Nina van Gorkom

Cetasikas by Nina van Gorkom

- Nhât Hanh, Thich (1988). The Heart of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press. ISBN 0-938077-11-2.

- Nhât Hanh, Thich (1999). The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching. NY: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0369-2..

- Trungpa, Chögyam (1976). The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation. Boulder: Shambhala. ISBN 0-87773-084-9.

- Kalupahana, David (1975). Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism. The University Press of Hawaii.

External links

- Khandavagga suttas (a selection), translated primarily by Thanissaro Bhikkhu.

Basic Scheme of the Five Aggregates, StudyBuddhism

Basic Scheme of the Five Aggregates, StudyBuddhism The Reasons for the Structure of the Five Aggregates, StudyBuddhism

The Reasons for the Structure of the Five Aggregates, StudyBuddhism Five skandhas, Rigpa Shedra Wiki

Five skandhas, Rigpa Shedra Wiki

Further reading

- Engle, Artemus B., The Inner Science of Buddhist Practice: Vasubhandu's Summary of the Five Heaps with Commentary by Sthiramati, Ithaca: Snow Lion, 2009

- Guenther, Herbert V. & Leslie S. Kawamura (1975), Mind in Buddhist Psychology: A Translation of Ye-shes rgyal-mtshan's "The Necklace of Clear Understanding". Dharma Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Videos

YouTube

Search for videos:

- Search YouTube for: Five skandhas Buddhism

Selected videos:

- Buddhism 101_fiveskandhas_1_3

- Description: Five Skandhas (Five Aggregates) by Ven. Thich Hue Hai at Dieu Phap Temple on October 2nd, 2011 at 3:00pm

- The Five Skandhas of Grasping and Non-Self, Dharma Talk by Br Phap Lai, 2018 06 08

- Description: The Five Skandhas of Grasping and Non-Self

Vimeo

Search for videos:

- Search Vimeo for: Five skandhas Buddhism

Selected videos:

- Ringu Tulku on the five skandhas

- Description: Using a commentary by Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche, 'The Gateway to Knowledge', [Vol 1], Ringu Tulku explains the five skandhas. This teaching goes into much detail on the skandha of form.

| This article includes content from Five skandhas on Wikipedia (view authors). License under CC BY-SA 3.0. |