Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra

Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra (T. dam pa'i chos padma dkar po'i mdo; C. miaofa lian hua jing/fahua jing 妙法蓮華經/法華經), or The Sutra of the White Lotus of Good Dharma, commonly known as the Lotus Sūtra, is one of the most influential Mahayana sutras.

Donald Lopez states:

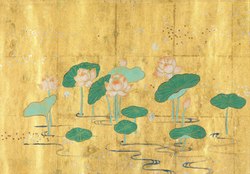

- The Lotus Sutra is arguably the most famous of all Buddhist texts. [...] The Lotus Sutra was composed in India, and in the Sanskrit language, where its title is Saddharmapuṇḍarīka Sūtra. This might be translated as the Discourse on the White Lotus of the True Doctrine. ...this title is rather “loaded” from a Buddhist perspective. It is not just a lotus (the traditional flower of Buddhism), but the white lotus, the best of lotuses. It does not just teach the dharma, the doctrine, but the true doctrine. As a sutra, or “discourse,” it is traditionally attributed to the Buddha himself.[1]

Lopez also states:

- Although composed in India, the Lotus Sutra became particularly important in China and Japan. In terms of Buddhist doctrine, it is renowned for two powerful proclamations by the Buddha. The first is that there are not three vehicles to enlightenment but one, that all beings in the universe will one day become buddhas. The second is that the Buddha did not die and pass into nirvana; in fact, his lifespan is immeasurable. The sutra is also famous for its parables, like the Parable of the Burning House and the Parable of the Prodigal Son. It was because of these parables that the Lotus Sutra became the first Buddhist text to be translated from Sanskrit into a European language (French). The Lotus Sutra has several dramatic scenes; perhaps the most famous is when a giant bejeweled stupa (a tomb of a buddha) emerges from the earth and a living buddha is found inside. Such scenes inspired hundreds of works of art across East Asia. At the Dunhuang cave complex in China, scenes from the Lotus Sutra are found in some seventy-five caves.[1]

Lopez also states:

- The anonymous authors of the Lotus Sutra presented a radical re-vision of both the Buddhist path and of the person of the Buddha. They did this with remarkable skill; they were clearly monks who were deeply versed in traditional Buddhist doctrine but were also deeply dissatisfied with the state of the Buddhist tradition as it existed around the beginning of the Common Era. [...] The authors were determined to portray their work as the words of the Buddha and thus have the Buddha constantly praise the Lotus Sutra, promising rewards to those who embrace it and punishments to those who reject it.[1]

This sutra's influence within Tibetan Buddhism is more limited than in East Asia. Within Tibetan Buddhism, this sutra serves as a reference for quotes regarding the view and practice for the Mahayana path.

Title

Sanskrit title:

- Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra

English translations for the title:

- Lotus Sutra

- Sutra of the White Lotus of the Good Dharma (Roberts 2022)[2]

- Sutra of the White Lotus of the True Dharma (Buswell & Lopez 2014)[3]

- Sūtra on the White Lotus of the Sublime Dharma (Shields 2013)[4]

Translations of this title into other languages include:

- Chinese: 妙法蓮華經; pinyin: Miàofǎ Liánhuá jīng, shortened to 法華經 Fǎhuá jīng

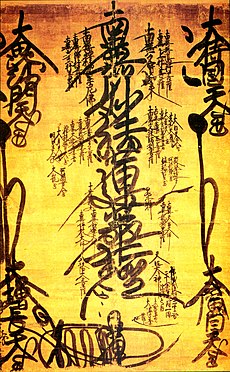

- Japanese: (妙法蓮華経 Myōhō Renge Kyō), Hokke-kyō, Hoke-kyō (法華経)

- Korean: Hangul: 묘법연화경; RR: Myobeop Yeonhwa gyeong, shortened to Beophwa gyeong

- Tibetan: དམ་ཆོས་པད་མ་དཀར་པོའི་མདོ, Wylie: dam chos padma dkar po'i mdo

Translations

Translations into Chinese

| Chinese canon |

|---|

| Mainstream texts |

| Mahayana sutras |

|

| Tantras |

|

Three translations of the Lotus Sūtra into Chinese are extant:[5][6][7][note 1]

- The Lotus Sūtra of the Correct Dharma (Cheng fa-hua ching), in ten volumes and twenty-seven chapters, translated by Dharmarakṣa in 286 CE.

- The Lotus Sūtra of the Wonderful Dharma (Miàofǎ Liánhuá jīng), in eight volumes and twenty-eight chapters, translated by Kumārajīva in 406 CE.

- The Supplemented Lotus Sūtra of the Wonderful Dharma (T´ien p´in miao-fa lien-hua-ching), in seven volumes and twenty-seven chapters, a revised version of Kumarajiva's text, translated by Jnanagupta and Dharmagupta in 601 CE.[9]

The Lotus Sūtra was originally translated from an Indic language into Chinese by Dharmarakṣa in 286 CE in Chang'an during the Western Jin Period (265-317 CE).[10][11] This early translation might have been from a Prakrit language, rather than Sanskrit.[note 2] Watson (1993) suggests that the text might have originally been composed in a Prakrit dialect and then later translated into Sanskrit to lend it greater respectability.[13]

This early translation by Dharmarakṣa was followed by a translation by Kumārajīva in 406 CE. Kumārajīva's translation is the most popular.[3]

In some Chinese and Japanese sources the Lotus Sūtra has been compiled together with two other sutras: the Innumerable Meanings Sutra and the Samantabhadra Meditation Sutra, which serve as a prologue and epilogue to the Lotus Sutra, respectively. This composite sutra is often called the Threefold Lotus Sūtra.[14]

Translation into Tibetan

| Tibetan canon |

|---|

| Mainstream texts |

| Mahayana sutras |

| Tantras |

Peter Alan Roberts states:

- The Tibetan translation was made during the reign of King Ralpachen (r. 815–38) as part of the translation project at Samye Monastery instituted by King Trisong Detsen (r. 742–98). The translators were Nanam Yeshé Dé, who was also the chief editor and whose name is in the colophon of no fewer than 380 texts in the Kangyur and Tengyur, three of which are his own original works in Tibetan, and the Indian translator Surendrabodhi, who did not come to Tibet until Ralpachen’s reign and is also listed as the translator of 43 texts.

- The Tibetan version matches in content the version translated into Chinese by Jñānagupta and Dharmagupta in 601–02, and also matches the Nepalese Sanskrit manuscripts. The last part of chapter 25 corresponds to the passage that first appeared in Chinese in the 601–02 translation and was subsequently added to Kumārajīva’s version. The Devadatta episode, which is not in Kumārajīva’s Chinese translation and is included as a separate chapter in Jñānagupta’s, forms part of chapter 11, “The Appearance of the Stūpa,” in both the Nepalese Sanskrit and the Tibetan. However, the transition in chapter 11 from the account of the floating stūpa to the Devadatta passage is abrupt. The Devadatta passage is also followed immediately, without a narrative transition, by the account of Prajñākūṭa, which might more gracefully have had its own chapter.

- Present in Tibetan and Sanskrit, but not in Chinese, are the last five verses of chapter 24, describing Avalokiteśvara in relation to Sukhāvatī and his future buddhahood. Some Tibetan versions contain a teaching that is emitted from the floating stūpa in chapter 11. As mentioned above, this teaching is not found in any extant Sanskrit manuscript, nor in the Chinese translations. Specifically, it is present in the Degé, Narthang, Lhasa, and Stok Palace Kangyurs, but not in the Yongle Peking, Lithang, Kangxi Peking, or Choné Kangyurs.

- As mentioned above, the only commentary on the sūtra in the Tengyur is an anonymous translation from the Chinese of the first eleven chapters of a commentary by Kuiji (632–682). In Tibet the Lotus Sūtra never gained the prominence it achieved in China, let alone in Japan; nor did it have even the status it retains in Nepalese Buddhism. Nevertheless, it has served through the centuries as a source of quotations for many authors of all schools of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly on the subject of the preeminence of the Mahāyāna.[2]

Translations into Western languages

From Nepalese Sanskrit manuscript

Eugène Burnouf completed a French translation based on a Nepalese Sanskrit manuscript in 1852:

- Burnouf, Eugène, trans. (1852), Le Lotus de la Bonne Loi: Traduit du sanskrit, accompagné d'un commentaire et de vingt et un mémoires relatifs au Bouddhisme, Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, ISBN 9780231142885

Hendrik Kern completed his English translation of an ancient Nepalese Sanskrit manuscript in 1884:

- Kern, Hendrik, trans. (1884), Saddharma Pundarîka or the Lotus of the True Law, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XXI, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 9780231142885

From Kumarajiva's Chinese text

Multiple translations of Kumarajiva's Chinese version have been made into Western languages.

English language translations include:

- Soothill, William Edward, trans. (1930), The Lotus of the Wonderful Law or The Lotus Gospel, Clarendon Press, pp. 15–36 (Abridged)

- Kato, Bunno; Tamura, Yoshirō; Miyasaka, Kōjirō, trans. (1975), The Threefold Lotus Sutra: The Sutra of Innumerable Meanings; The Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Law; The Sutra of Meditation on the Bodhisattva Universal Virtue (PDF), New York/Tōkyō: Weatherhill & Kōsei Publishing, Archived from the original on 2014-04-21

- Murano, Senchū (trans.) (1974), The Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Law, Tokyo: Nichiren Shu Headquarters, ISBN 2213598576

- Hurvitz, Leon (2009), Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma : The Lotus Sutra) (Rev. ed.), New York: Columbia university press, ISBN 023114895X

- Kuo-lin, Lethcoe, ed. (1977), The Wonderful Dharma Lotus Flower Sutra with the Commentary of Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua, San Francisco: Buddhist Text Translation Society

- Kubo, Tsugunari; Yuyama, Akira, trans. (2007), The Lotus Sutra (PDF), Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, ISBN 978-1-886439-39-9, Archived from the original on 2015-05-21

- Watson, Burton, tr. (1993), The Lotus Sutra, Columbia University Press, ISBN 023108160X

- Reeves, Gene, trans. (2008), The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic, Boston: Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-571-3

Other translations

- French:

- Robert, Jean-Noël (1997), Le Sûtra du Lotus: suivi du Livre des sens innombrables, Paris: Fayard, ISBN 2213598576

- Spanish

- Tola, Fernando; Dragonetti, Carmen (1999), El Sūtra del Loto de la verdadera doctrina: Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra, México, D.F.: El Colegio de México: Asociación Latinoamericana de Estudios Budistas, ISBN 968120915X

- German

- Borsig, Margareta von, trans. (2009), Lotos-Sutra - Das große Erleuchtungsbuch des Buddhismus, Verlag Herder, ISBN 978-3-451-30156-8

- Deeg, Max (2007), Das Lotos-Sūtra, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, ISBN 9783534187539

From Tibetan text

The following translation from the Tibetan text is published by the 84000 translation group:

Peter Alan Roberts (2022), The White Lotus of the Good Dharma, 84000 Reading Room

Peter Alan Roberts (2022), The White Lotus of the Good Dharma, 84000 Reading Room

"The Tibetan version matches in content the version translated into Chinese by Jñānagupta and Dharmagupta in 601–02, and also matches the Nepalese Sanskrit manuscripts."[2]

Influence on Buddhist traditions

India

The Lotus Sutra was frequently cited in Indian works by Nagarjuna, Vasubandhu, Candrakirti, Santideva and several authors of the Madhyamaka and the Yogacara school.[15] The only extant Indian commentary on the Lotus Sutra is attributed to Vasubandhu.[16][17]

East Asia

The Lotus Sutra was particularly important in China and Japan.[18]

China

Tao Sheng, a fifth-century Chinese Buddhist monk wrote the earliest extant commentary on the Lotus Sūtra.[19][20] Tao Sheng was known for promoting the concept of Buddha nature and the idea that even deluded people will attain enlightenment.

Daoxuan (596-667) of the Tang Dynasty wrote that the Lotus Sutra was "the most important sutra in China".[21]

Zhiyi, the generally credited founder of the Tiantai school of Buddhism, was the student of Nanyue Huisi[22] who was the leading authority of his time on the Lotus Sūtra.[23] Zhiyi's philosophical synthesis saw the Lotus Sūtra as the final teaching of the Buddha and the highest teaching of Buddhism.[24] He wrote two commentaries on the sutra: Profound meanings of the Lotus Sūtra and Words and phrases of the Lotus Sūtra. Zhiyi also linked the teachings of the Lotus Sūtra with the Buddha nature teachings of the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra and made a distinction between the "Eternal Buddha" Vairocana and the manifestations. In Tiantai, Vairocana (the primeval Buddha) is seen as the 'Bliss body' – Sambhogakāya – of the historical Gautama Buddha.[24]

Japan

The Lotus Sūtra is an important sutra in Tiantai[25] and correspondingly, in Japanese Tendai (founded by Saicho, 767–822). Tendai Buddhism was the dominant form of mainstream Buddhism in Japan for many years and the influential founders of popular Japanese Buddhist sects including Nichiren, Honen, Shinran and Dogen[26] were trained as Tendai monks.

Nichiren believed that the Lotus Sūtra is "the Buddha´s ultimate teaching",[28], and that chanting the title of the Lotus Sūtra – Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō – was the only way to practice Buddhism in the degenerate age of Dharma decline and was the highest practice of Buddhism.[24]

Tibet

Peter Alan Roberts states:

- In Tibet the Lotus Sūtra never gained the prominence it achieved in China, let alone in Japan; nor did it have even the status it retains in Nepalese Buddhism. Nevertheless, it has served through the centuries as a source of quotations for many authors of all schools of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly on the subject of the preeminence of the Mahāyāna.[2]

The only commentary on the sūtra in the Tibetan Tengyur is an anonymous translation from the Chinese of the first eleven chapters of a commentary by Kuiji (632–682).[2]

See also

- Amitabha Sutra

- Flower Sermon

- Hokke Gisho, an annotated Japanese version of the sutra.

Notes

- ↑ Weinstein states: "Japanese scholars demonstrated decades ago that this traditional list of six translations of the Lotus lost and three surviving-given in the K'ai-yiian-lu and elsewhere is incorrect. In fact, the so-called "lost" versions never existed as separate texts; their titles were simply variants of the titles of the three "surviving" versions."[8]

- ↑ Jan Nattier has recently summarized this aspect of the early textual transmission of such Buddhist scriptures in China thus, bearing in mind that Dharmarakṣa's period of activity falls well within the period she defines: "Studies to date indicate that Buddhist scriptures arriving in China in the early centuries of the Common Era were composed not just in one Indian dialect but in several . . . in sum, the information available to us suggests that, barring strong evidence of another kind, we should assume that any text translated in the second or third century AD was not based on Sanskrit, but one or other of the many Prakrit vernaculars."[12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ganga 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4

Peter Alan Roberts (2022), The White Lotus of the Good Dharma (Introduction), 84000 Reading Room

Peter Alan Roberts (2022), The White Lotus of the Good Dharma (Introduction), 84000 Reading Room

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra.

- ↑ Shields 2013, p. 512.

- ↑ Reeves 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ The English Buddhist Dictionary Committee 2002.

- ↑ Shioiri 1989, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Weinstein 1977, p. 90.

- ↑ Stone 2003, p. 471.

- ↑ Taisho vol.9, pp. 63-134

- ↑ Zürcher 2006, p. 57-69.

- ↑ Nattier 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ Watson 1993, p. IX.

- ↑ Buswell & Lopez 2014, s.v. Fahua sanbu [jing].

- ↑ Mochizuki 2011, pp. 1169-1177.

- ↑ Groner 2014, p. 5.

- ↑ Abbot 2013, p. 87.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJG2016 - ↑ Teiser 2009.

- ↑ Kim 1985, pp. 3.

- ↑ Groner 2014.

- ↑ Magnin 1979.

- ↑ Kirchner 2009, p. 193.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Williams 1989, p. 162.

- ↑ Groner 2000, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Tanahashi 1995, p. 4.

- ↑ Stone 2003, p. 277.

- ↑ Stone 2009, p. 220.

Sources

- Abbot, Terry, trans. (2013), The Commentary on the Lotus Sutra, in: Tsugunari Kubo; Terry Abbott; Masao Ichishima; David Wellington Chappell, Tiantai Lotus Texts (PDF), Berkeley, California: Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai America, pp. 83–149, ISBN 978-1-886439-45-0

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University

Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (2014), The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University- Ganga, Jessica (2016), Donald Lopez on the Lotus Sutra, Princeton University Press Blog

- Groner, Paul (2000), Saicho: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0824823710

- Groner, Paul; Stone, Jacqueline I. (2014), "Editors' Introduction: The "Lotus Sutra" in Japan", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 41 (1): 1–23, archived from the original on June 14, 2014

- Kim, Young-Ho (1985), Tao-Sheng's Commentary on the Lotus Sutra: A Study and Translation, dissertation, Albany, NY.: McMaster University, Archived from the original on February 3, 2014

- Kirchner, Thomas Yuho; Sasaki, Ruth Fuller (2009), The Record of Linji, University of Hawaii Press, p. 193, ISBN 9780824833190

- Kurata, Tamura; Tamura, Yoshirō; translated by Edna B. (1987), Kurata, Bunsaku; Tamura, Yoshio, eds., Art of the Lotus Sutra: Japanese masterpieces, Tokyo: Kōsei Pub. Co., ISBN 4333010969

- Mochizuki, Kaie (2011). "How Did the Indian Masters Read the Lotus Sutra? -". Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. 59 (3): 1169–1177.

- Nattier, Jan (2008), A guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Translations (PDF), International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Soka University, ISBN 9784904234006, Archived from the original on July 12, 2012

- Robert, Jean Noël (2011), "On a Possible Origin of the "Ten Suchnesses" List in Kumārajīva's Translation of the Lotus Sutra", Journal of the International College for Postgraduate Buddhist Studies, 15: 63

- Shields, James Mark (2013), Political Interpretations of the Lotus Sutra. In: Steven M. Emmanuel, ed. A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy, London: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9781118324004

- Shioiri, Ryodo (1989), The Meaning of the Formation and Structure of the Lotus Sutra. In: George Joji Tanabe; Willa Jane Tanabe, eds. The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 15–36, ISBN 978-0-8248-1198-3

- Stone, Jacqueline, I. (1998), Chanting the August Title of the Lotus Sutra: Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan. In: Payne, Richard, K. (ed.); Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 116–166, ISBN 0-8248-2078-9, Archived from the original on 2015-01-04

- Stone, Jacqueline, I. (2003), "Lotus Sutra". In: Buswell, Robert E. ed.; Encyclopedia of Buddhism vol. 1, Macmillan Reference Lib., ISBN 0028657187

- Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (2003), Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2771-7

- Stone, Jacqueline, I. (2009), Realizing This World as the Buddha Land, in Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; eds.; Readings of the Lotus Sutra, Columbia University Press, pp. 209–236, ISBN 0028657187

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki (1995), Moon in a Dewdrop, p. 4, ISBN 9780865471863

- Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (2009), Interpreting the Lotus Sutra; in: Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; eds. Readings of the Lotus Sutra, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1–61, ISBN 9780231142885

- The English Buddhist Dictionary Committee (2002), The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Tōkyō: Soka Gakkai, ISBN 978-4-412-01205-9

- Portable Buddhist Shrine, The Walters Art Museum

- Watson, Burton, tr. (2009), The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and Closing Sutras, Tokyo: Soka Gakkai, ISBN 023108160X

- Weinstein, Stanley (1977), "Review: Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma, by Leon Hurvitz", The Journal of Asian Studies, 37 (1): 89–90, doi:10.2307/2053331

- Williams, Paul (1989), Mahāyāna Buddhism: the doctrinal foundations, 2nd Edition, Routledge, ISBN 9780415356534

- Zürcher, Erik (2006). The Buddhist Conquest of China, Sinica Leidensia (Book 11), Brill; 3rd edition. ISBN 9004156046

Further reading

- Hanh, Thich Nhat (2003). Opening the heart of the cosmos: insights from the Lotus Sutra. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax. ISBN 1888375337.

- Hanh, Thich Nhat (2009). Peaceful action, open heart: lessons from the Lotus Sutra. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax Press. ISBN 1888375930.

- Ikeda, Daisaku; Endo, Takanori; Saito, Katsuji; Sudo, Haruo (2000). Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra: A Discussion, Volume 1. Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press. ISBN 978-0915678693.

- Lopez, Donald (2016), The Lotus Sutra: A Biography, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691152209

- Niwano, Nikkyō (1976). Buddhism for today : a modern interpretation of the Threefold Lotus sutra (PDF) (1st ed.). Tokyo: Kosei Publishing Co. ISBN 4333002702. Archived from the original on 2013-11-26.

- Rawlinson, Andrew (1972). Studies in the Lotus Sutra (Saddharmapuṇḍarīka), Ph. D. Thesis, University of Lancaster. OCLC 38717855

- Silk, Jonathan (2001), "The place of the Lotus Sutra in Indian Buddhism" (PDF), The Journal of Oriental Studies, 11: 87–105, Archived from the original on August 26, 2014

- Silk, Jonathan A. (2012), "Kern and the Study of Indian Buddhism With a Speculative Note on the Ceylonese Dhammarucikas" (PDF), The Journal of the Pali Text Society, XXXI: 125–54

- Silk, Jonathan; Hinüber, Oskar von; Eltschinger, Vincent; eds. (2016). "Lotus Sutra", in Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Volume 1: Literature and Languages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 144–157

- Tamura, Yoshiro (2014). Introduction to the lotus sutra. [S.l.]: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 1614290806.

- Tanabe, George J.; Tanabe, Willa Jane (ed.) (1989). The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1198-4.

- Tola, Fernando, Dragonetti, Carmen (2009). Buddhist positiveness: studies on the Lotus Sūtra, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-3406-4.

- Vetter, Tilmann (1999), "Hendrik Kern and the Lotus Sutra" (PDF), Annual Report of The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University, 2: 129–142

- Yuyama, Akira (1970). A Bibliography of the Sanskrit-Texts of the Sadharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra. Faculty of Asian Studies in Association With Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

- Yuyama, Akira (1998), Eugene Burnouf: The Background to his Research into the Lotus Sutra, Bibliotheca Philologica et Philosophica Buddhica, Vol. III (PDF), Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, ISBN 4-9980622-2-0, Archived from the original on 2007-07-05

External links

- How to Read the Lotus Sutra, Tricycle.org

- An 1884 English translation from Sanskrit by H.Kern from the Sacred Texts Web site

- An English translation by the Buddhist Text Translation Society

The White Lotus of the Good Dharma

The White Lotus of the Good Dharma

| This article includes content from Lotus Sutra on Wikipedia (view authors). License under CC BY-SA 3.0. |