Gautama Buddha

| This content is a work in progress. |

.jpg/300px-Buddha_in_Sarnath_Museum_(Dhammajak_Mutra).jpg)

Gautama Buddha, also known as Shakyamuni Buddha, or simply the Buddha, was an Indian sage on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. He is believed to have lived and taught in northeastern India sometime between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE.[1]

When referring to the period before he became enlightened, the Buddha is known as Siddhārtha Gautama (Sanskrit) or Siddhattha Gotama (Pali). Siddhartha, his given name, means "one who achieves his goals"; Gautama is his family name.

Gautama Buddha is believed by Buddhists to have been a fully awakened being who taught the true path to the cessation of suffering (dukkha) and the attainment of liberation (nirvana). Accounts of his life, discourses and monastic rules are believed by Buddhists to have been summarized after his death and memorized by his followers. Various collections of teachings attributed to him were passed down by oral tradition and first committed to writing about 400 years after his death.

Historical Siddhārtha Gautama

.png/250px-Mahajanapadas_(c._500_BCE).png)

Scholars are hesitant to make unqualified claims about the historical facts of the Buddha's life. Most accept that he lived, taught and founded a monastic order, but do not accept many of the details contained in traditional biographies.[2][3]

According to author Michael Carrithers, while there are good reasons to doubt the traditional account, "the outline of the life must be true: birth, maturity, renunciation, search, awakening and liberation, teaching, death."[4] In her biography of the Buddha, Karen Armstrong writes,

- It is obviously difficult, therefore, to write a biography of the Buddha that meets modern criteria, because we have very little information that can be considered historically sound... [but] we can be reasonably confident Siddhatta Gotama did indeed exist and that his disciples preserved the memory of his life and teachings as well as they could.[5]

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhārtha was born in a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the northeastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[6]

The Buddha was born into the Shakya clan, which historians believe to have been organized into either an oligarchy or a republic. Historians suggest that Siddhartha's father was likely an important figure in the republic or oligarchy, rather than a "king" as described in the traditional biographies.[6]

Most scholars accept that he lived, taught and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada era in India during the reign of Bimbisara, the ruler of the Magadha empire, and died during the early years of the reign of Ajatshatru who was the successor of Bimbisara, thus making him a younger contemporary of Mahavira, the Jain teacher.[7][8]

Influences

Apart from the Vedic Brahmins, the Buddha's lifetime coincided with the flourishing of other influential sramana schools of thoughts like Ājīvika, Cārvāka, Jain, and Ajñana. It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahāvīra, Pūraṇa Kassapa , Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, whose viewpoints the Buddha most certainly must have been acquainted with and influenced by.[9][10][note 1] Indeed, Sariputta and Maudgalyāyana, two of the foremost disciples of the Buddha, were formerly the foremost disciples of Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, the skeptic.[11] There is also evidence to suggest that the two masters, Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, were indeed historical figures and they most probably taught Buddha two different forms of meditative techniques.[12]

Birth and death

The times of Gautama's birth and death are uncertain. Most historians in the early 20th century dated his lifetime as circa 563 BCE to 483 BCE.[13][14] More recently his death is dated later, between 411 and 400 BCE, while at a symposium on this question held in 1988,[15][16][17] the majority of those who presented definite opinions gave dates within 20 years either side of 400 BCE for the Buddha's death.[13][18][note 3] These alternative chronologies, however, have not yet been accepted by all historians.[24][25][note 5]

According to the Buddhist tradition, Gautama was born in Lumbini, nowadays in modern-day Nepal, and raised in Kapilavastu (Shakya capital), which may either be in present day Tilaurakot, Nepal or Piprahwa, India.[note 2]

Shakya clan

The evidence of the early texts suggests that Siddhārtha Gautama was born into the Shakya clan, a community that was on the periphery, both geographically and culturally, of the northeastern Indian subcontinent in the 5th century BCE.[6] According to Gombrich, they seem to have had no cast system, but did have servants.

Gombrich states, "Some historians call [Shakya] an oligarchy, some a republic; certainly it was not a brahminical monarchy, and makes more than dubious the later story that the future Buddha’s father was the local king."[33] In this view, Siddhartha's father was more likely an important figure in the republic or oligarchy, rather than a traditional monarch.

Historians believe that the Shakyas were self governing and heads of housholds met in council to discuss problems and reach unanimous decisions. According to Gombrich, this gave the Buddha a model of a castless society; in the Sangha he instituted rank based on seniority counted from ordination.[6]

Birthplace

The Buddhist tradition regards Lumbini, present-day Nepal, to be the birthplace of the Buddha.[34][note 2] According to tradition, he grew up in Kapilavastu.[note 2] The exact site of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown. It may have been either Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, present-day India,[31] or Tilaurakot, present-day Nepal.[35] Both places belonged to the Sakya territory, and are located only 15 miles apart from each other.[35]

Siddharta Gautama was born as a Kshatriya,[36][note 7] the son of Śuddhodana, "an elected chief of the Shakya clan",[1] whose capital was Kapilavastu, and who were later annexed by the growing Kingdom of Kosala during the Buddha's lifetime. Gautama was the family name. His mother, Queen Maha Maya (Māyādevī) was a Koliyan princess.

Travels and teaching

The Buddha spent about 45 years of his life teaching the dharma. He is said to have traveled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to servants, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka.[38] Although the Buddha's language remains unknown, it's likely that he taught in one or more of a variety of closely related Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, of which Pali may be a standardization.

The sangha, the Buddha's disciples, would travel throughout the subcontinent, expounding the dharma.

Written records

No written records about Gautama have been found from his lifetime or some centuries thereafter. One edict of Emperor Ashoka, who reigned from circa 269 BCE to 232 BCE, commemorates the Emperor's pilgrimage to the Buddha's birthplace in Lumbini. Another one of his edict mentions several Dhamma texts, establishing the existence of a written Buddhist tradition at least by the time of the Mauryan era and which may be the precursors of the Pāli Canon.[39][note 8] The oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts are the Gandhāran Buddhist texts, reported to have been found in or around Haḍḍa near Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan and now preserved in the British Library. They are written in the Kharoṣṭhī script and the Gāndhārī language on twenty-seven birch bark scrolls, and they date from the first century BCE to the third century CE.[web 8]

Traditional life story

There are multiple accounts of the life of the Buddha within Buddhist literature. These accounts generally agree on the broad outlines of his life story, though there are differences in detail and interpretation.[40]

Alexander Berzin states:

- Generally, traditional biographies of great Buddhist masters, including Buddha himself, were compiled for didactic purposes, not for the sake of mere historical records. More specifically, the biographies were fashioned in such a way as to teach and inspire Buddhist followers to pursue the spiritual path to liberation and enlightenment. In order to benefit from Buddha’s life story, we need to understand it within this context, and analyze the lessons that we can learn from it.[41]

The account below follows the broad outline of Buddha's life, according to traditional sources.

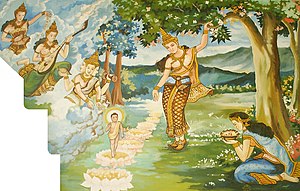

Birth

Gautama Buddha's parents were King Śuddhodana and Queen Maya, who were the rulers of the Shakya kingdom of Northern India. His given name was Siddhartha.

The King and Queen lived in the Shakya capital of Kapilavastu. Following the traditional custom of the time, when Queen Maya knew the time of her son's birth was drawing near, she began to travel to her father's home in Kapilavastu, in order to give birth to the child there. However, the queen was unable to reach her destination before giving birth, and her son was born in a garden beneath a sal tree in the region of Lumbini (in present-day Nepal).

Siddhartha's mother, Queen Maya died soon after giving birth. Siddhartha would be raised by his father, King Śuddhodana, and his mother's younger sister, Maha Pajapati.

Life in the palace

Siddhartha's father, King Śuddhodana, gave him the name Siddhartha, meaning "one who achieves his goals".

Soon after the birth of Siddhartha, Śuddhodana invited a group of eight brahmin sages to his court to examine the child and predict his future. The sages prophesied that Siddhartha would either become a great king and military conqueror (chakravartin) or an enlightened spiritual guide (buddha).

Śuddhodana was eager for his son to become a great king and conqueror. But he was concerned that Siddhartha might choose the spiritual path and renounce his worldly inheritance.

- In an effort to assure that his son's spiritual nature was never awakened, the King insulated Siddhartha from all pain and suffering. He was surrounded by wealth and pleasure, his every wish granted. Orders were given that no unpleasantness would intrude upon Siddhartha’s life of courtly pleasures and so all signs of illness, aging, and mortality were hidden from him.[42]

Thus, as a young man, Siddhartha wore robes of the finest silk, ate the best food and was surrounded by beautiful dancing girls. He was extremely handsome and he excelled at his studies and at every type of sporting contest. His father arranged for him to marry a young woman of exceptional grace and beauty, Yasodhara. Siddhartha and Yasodhara lived together in peace and harmony for many years, and they had a son together.

Yet despite all of this, Siddhartha still had not yet been outside the palace walls. His curiosity grew stronger and stronger and he pleaded with his father to allow him to venture beyond the palace gates. Finally, when Siddhartha reached the age of 29, his father relented and allowed him to visit the world outside the palace gates.

The four sights

Siddhartha ventured beyond the gates with his faithful charioteer Channa and they had a series of encounters known as the four sights. In these encounters, Siddhartha and Channa first encountered an old man, then a sick man, and then a corpse. From these three encounters Siddhartha began to understand the nature of suffering in the world. Finally, they met an ascetic holy man (śramaṇa), who appeared to be content and at peace with the world.

These encounters had a profound impact on Siddhartha. Through the first three sights, Siddhartha came to understand that despite the luxury of his surroundings, and despite the immense wealth and power of his family, both he himself and everyone he loved would eventually have to face the sufferings of old age, sickness and death. And he was powerless to stop this. Siddhartha was also inspired by the holy man who was seeking a path beyond suffering, and Siddhartha resolved that he too would seek that path in order that he could lead his family beyond suffering.

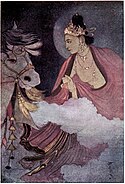

Renunciation

Siddhartha made the decision to renounce his worldly life and follow the path of an ascetic spiritual seeker. According to one account, late one night, after the rest of the household had gone to sleep, Siddhartha ordered Channa the charioteer to prepare his horse, and together they slipped unnoticed outside the palace gates. They rode to the edge of a nearby forest, and once there, Siddhartha informed Channa that he was renouncing his worldly life to become a seeker of truth. As a sign of his renunciation, Siddhartha cut off his long, beautiful hair and discarded his royal robes. Siddhartha instructed Channa to return to the palace and inform his father of his decision, and then he walked off into the forest.

Spiritual quest

After renouncing his worldly life, Siddhartha sought out the great spiritual teachers of his day. He studied with several teachers, and in each case, he mastered the meditative techniques which they taught. But he found that the meditation techniques that he learned from these teachers did not provide a permanent end to suffering, so he continued his quest. He next joined a group of five other ascetics (śramaṇa), led by a holy man named Kondañña. For the next several years, Siddhartha practiced extreme austerities along with his five companions. These austerities included prolonged fasting, breath-holding, and exposure to pain. He almost starved himself to death in the process.

Eventually Siddhartha realized that he had taken this kind of practice to its limit, and had not put an end to suffering. In a pivotal moment, as he was near death, Siddhartha accepted milk and rice from a village girl and began to regain his strength. He then devoted himself to meditation, taking in the nourishment that he needed, but not more than that. He would later describe his new approach as the Middle Way: a path of moderation between the extremes of self-indulgence and self-denial.

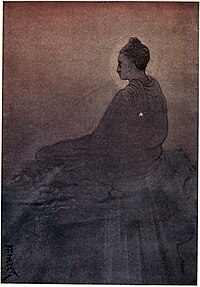

Enlightenment

At the age of 35, Siddhartha sat in meditation under a fig tree — now known as the Bodhi tree — and he vowed not to rise before achieving enlightenment (bodhi). After many days, he finally destroyed the fetters of his mind, thereby liberating himself from the cycle of suffering and rebirth (saṃsāra), and arose as a fully enlightened being (samyaksambuddha).

According to some accounts, after his awakening, the Buddha debated with himself whether or not he should teach the Dharma to others.[note 9] He was concerned that humans were so overpowered by ignorance (avidya), greed (raga) and hatred (dvesha) that they would not understand his dharma, which is subtle, deep and difficult to grasp. However, while he was contemplating this, he was approached by a being from the heavenly realms (Brahma Sahampati), who urged the Buddha to teach, arguing that at least some people will understand the dharma. The Buddha relented, and agreed to teach.

First teaching

After a period of deep reflection, the Buddha sought out his five former companions (with whom he had practiced austerities). He found them in a deer park in Sarnath, northern India.

There he gave his first teaching to his former companions, in which he explained his middle way approach and the four noble truths. Traditionally, it is said the Buddha "set in motion the Wheel of Dharma" when he gave this first teaching; this teaching is recorded in The Discourse That Sets Turning the Wheel of Truth (Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta).

The Buddha spent the rest of his life traveling throughout northeastern India and teaching the path of awakening he had discovered.

The first sangha

The Buddha along with his first five followers are said to have formed the first saṅgha: the company of Buddhist monks. As the Buddha traveled and continued teaching, he attracted many more followers, many of whom became monks and nuns, and many who became lay followers.

Return to Kapilavastu to teach his family

Upon hearing of Siddhartha's awakening, his father King Śuddhodana sent many requests to ask the Buddha to return to Kapilavastu. Two years after his awakening, the Buddha agreed to return to Kapilavastu, and made a two-month journey by foot, teaching the dharma as he went. When he reached his father's home in Kapilavastu, he taught the dharma to his father and his extended family. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. The Buddha's cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arhat.

Of the Buddha's disciples, Sariputta, Maudgalyayana, Mahakasyapa, Ananda and Anuruddha are believed to have been the five closest to him.

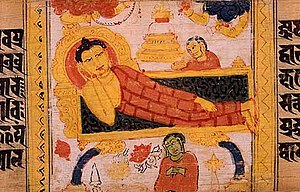

Mahaparinirvana

At the age of 80, the Buddha fell ill in the town of Kushinagar in northern India. At this time, he said to his attendant Ananda:

- I am now grown old, Ānanda, and full of years; my journey is done and I have reached my sum of days; I am turning eighty years of age. And just as a worn out cart is kept going with the help of repairs, so it seems is the Tathāgata’s body kept going with repairs.[43]

When Ananda become despondent, the Buddha said to him:

- Enough, Ānanda, do not sorrow, do not lament. Have I not formerly explained that it is the nature of things that we must be divided, separated, and parted from all that is beloved and dear? How could it be, Ānanda, that what has been born and come into being, that what is compounded and subject to decay, should not decay? It is not possible.[43]

The Buddha then passed away. He death is considered to be a parinirvana, a complete release from the cycle of existence (samsara).

The Buddha's body was cremated and the relics were placed in monuments or stupas, some of which are believed to have survived until the present.

Traditional biographical sources

There are multiple accounts of the life of the Buddha within Buddhist literature. These accounts generally agree on the broad outlines of his life story, though there are differences in detail and interpretation.[40] The sources for these accounts include:

- Buddhacarita,

- Lalitavistara Sūtra,

- Mahāvastu, and

- Nidānakathā.[44]

Of these, the Buddhacarita[45][46][47] is considered to be the earliest full biography. This text is an epic poem written by the poet Aśvaghoṣa, and dating around the beginning of the 2nd century CE.[44]

The Lalitavistara Sūtra is thought to be the next oldest biography, a Mahāyāna/Sarvāstivāda biography dating to the 3rd century CE.[48]

The Mahāvastu from the Mahāsāṃghika Lokottaravāda tradition is another major biography, composed incrementally until perhaps the 4th century CE.[48]

The Dharmaguptaka biography of the Buddha is the most exhaustive, and is entitled the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra,[49] and various Chinese translations of this date between the 3rd and 6th century CE.

Lastly, the Nidānakathā is from the Theravāda tradition in Sri Lanka and was composed in the 5th century CE by Buddhaghoṣa.[50]

Additional sources from the Pali Canon include the Jātakas, the Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14), and the Achariyabhuta Sutta (MN 123) which include selective accounts that may be older, but are not full biographies. The Jātakas retell previous lives of Gautama as a bodhisattva, and the first collection of these can be dated among the earliest Buddhist texts.[51] The Mahāpadāna Sutta and Achariyabhuta Sutta both recount miraculous events surrounding Gautama's birth, such as the bodhisattva's descent from Tuṣita Heaven into his mother's womb.

Meaning of "Buddha"

The word Buddha means "awakened one" or "the enlightened one". "Buddha" is also used as a title for the first awakened being in an era. In most Buddhist traditions, Siddhartha Gautama is regarded as the Supreme Buddha (Pali sammāsambuddha, Sanskrit samyaksaṃbuddha) of our age.[note 10]

Relics

After his death, Buddha's cremation relics were divided amongst 8 royal families and his disciples; centuries later they would be enshrined by King Ashoka into 84,000 stupas.[web 9][52][53]

Physical characteristics

Traditionally, the Buddha's physical body is said to possess:

- Mahapurusalaksana - thirty-two major marks of a great man

- Minor marks of a great person - eighty minor marks

Within Buddhist cosmology, these physical marks are shared by both buddhas and chakravartins. However the marks are more clear and distinct on the body of a buddha. The Buddha also has a few marks that are not found on the chakravartin, such as the protuberance on the crown of the Buddha's head.[54]

Notes

- ↑ According to Alexander Berzin, "Buddhism developed as a shramana school that accepted rebirth under the force of karma, while rejecting the existence of the type of soul that other schools asserted. In addition, the Buddha accepted as parts of the path to liberation the use of logic and reasoning, as well as ethical behavior, but not to the degree of Jain asceticism. In this way, Buddhism avoided the extremes of the previous four shramana schools."[web 1]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 According to the Buddhist tradition, following the Nidanakatha,[web 5] the introductory to the Jataka tales, the stories of the former lives of the Buddha, Gautama was born in Lumbini, present-day Nepal.[web 6][web 7] In the mid-3rd century BCE the Emperor Ashoka determined that Lumbini was Gautama's birthplace and thus installed a pillar there with the inscription: "...this is where the Buddha, sage of the Śākyas (Śākyamuni), was born."[27]

Kapilavastu was the place where he grew up:[28][note 6]- Warder: "The Buddha [...] was born in the Sakya Republic, which was the city state of Kapilavastu, a very small state just inside the modern state boundary of Nepal against the Northern Indian frontier.[1]

- Walsh: "He belonged to the Sakya clan dwelling on the edge of the Himalayas, his actual birthplace being a few miles north of the present-day Northern Indian border, in Nepal. His father was in fact an elected chief of the clan rather than the king he was later made out to be, though his title was raja – a term which only partly corresponds to our word 'king'. Some of the states of North India at that time were kingdoms and others republics, and the Sakyan republic was subject to the powerful king of neighbouring Kosala, which lay to the south".[30] The exact location of ancient Kapilavastu is unknown.[28] It may have been either Piprahwa in Uttar Pradesh, northern India,[31][28] or Tilaurakot, present-day Nepal.[32][28] The two cities are located only fifteen miles from each other.[32]

- ↑

- 411–400: Dundas 2002, p. 24: "...as is now almost universally accepted by informed Indological scholarship, a re-examination of early Buddhist historical material, [...], necessitates a redating of the Buddha's death to between 411 and 400 BCE..."

- 405: Richard Gombrich[19][20][21][22]

- Around 400: See the consensus in the essays by leading scholars in Narain, Awadh Kishore, ed. (2003), The Date of the Historical Śākyamuni Buddha, New Delhi: BR Publishing, ISBN 81-7646-353-1.

- According to Pali scholar K. R. Norman, a life span for the Buddha of c. 480 to 400 BCE (and his teaching period roughly from c. 445 to 400 BCE) "fits the archaeological evidence better".[23] See also Notes on the Dates of the Buddha Íåkyamuni.

- ↑ See "Ambattha Sutta", Digha Nikaya 3, were Vajrapani frightens an arrogant young Brahman, and the superiority of Kashatriyas over Brahmins is established.[web 4]

- ↑ In 2013, archaeologist Robert Coningham found the remains of a Bodhigara, a tree shrine, dated to 550 BCE at the Maya Devi Temple, Lumbini, speculating that it may possible be a Buddhist shrine. If so, this may push back the Buddha's birth date.[web 2] Archaeologists caution that the shrine may represent pre-Buddhist tree worship, and that further research is needed.[web 2]

Richard Gombrich has dismissed Coningham's specualtions as "a fantasy", noting that Coningham lacks the necessary expertise on the history of early Buddhism.[web 3]

Geoffrey Samuels notes that several locations of both early Buddhism and Jainism are closely related to Yaksha-worship, that several Yakshas were "converted" to Buddhism, a well-known example being Vajrapani,[note 4] and that several Yaksha-shrines, where trees were worshipped, were converted into Buddhist holy places.[26] - ↑ Some sources mention Kapilavastu as the birthplace of the Buddha. Gethin states: "The earliest Buddhist sources state that the future Buddha was born Siddhārtha Gautama (Pali Siddhattha Gotama), the son of a local chieftain — a rājan — in Kapilavastu (Pali Kapilavatthu) what is now the Indian–Nepalese border."[29] Gethin does not give references for this statement.

- ↑ According to Geoffrey Samuel, the Buddha was born as a Kshatriya,[36] in a moderate Vedic culture at the central Ganges Plain area, where the shramana-traditions developed. This area had a moderate Vedic culture, where the kshatriyas were the highest varna, in contrast to the Brahmanic ideology of Kuru-Panchala, were the Brahmins had become the highest varna.[36] Both the Vedic culture and the shramana tradition contributed to the emergence of the so-called "Hindu-synthesis" around the start of the Common Era.[37][36]

- ↑ Minor Rock Edict Nb3: "These Dhamma texts – Extracts from the Discipline, the Noble Way of Life, the Fears to Come, the Poem on the Silent Sage, the Discourse on the Pure Life, Upatisa's Questions, and the Advice to Rahula which was spoken by the Buddha concerning false speech – these Dhamma texts, reverend sirs, I desire that all the monks and nuns may constantly listen to and remember. Likewise the laymen and laywomen."[39]

Dhammika:"There is disagreement amongst scholars concerning which Pali suttas correspond to some of the text. Vinaya samukose: probably the Atthavasa Vagga, Anguttara Nikaya, 1:98-100. Aliya vasani: either the Ariyavasa Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, V:29, or the Ariyavamsa Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, II: 27-28. Anagata bhayani: probably the Anagata Sutta, Anguttara Nikaya, III:100. Muni gatha: Muni Sutta, Sutta Nipata 207-221. Upatisa pasine: Sariputta Sutta, Sutta Nipata 955-975. Laghulavade: Rahulavada Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya, I:421."[39] - ↑ E.g. the Āyācana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya VI.1)

- ↑ Hypothetical root budh "perceive" 1. Pali buddha – "understood, enlightened", masculine "the Buddha"; Aśokan (the language of the Inscriptions of Aśoka) Budhe nominative singular; Prakrit buddha – ‘ known, awakened ’; Waigalī būdāī, "truth"; Bashkarīk budh "he heard"; Tōrwālī būdo preterite of bū, "to see, know" from bṓdhati; Phalūṛa búddo preterite of buǰǰ , "to understand" from búdhyatē; Shina Gilgitī dialect budo, "awake"; Gurēsī dialect budyōnṷ intransitive "to wake"; Kashmiri bọ̆du, "quick of understanding (especially of a child)"; Sindhī ḇudho, past participle (passive) of ḇujhaṇu, "to understand" from búdhyatē, West Pahāṛī buddhā, preterite of bujṇā, "to know"; Sinhalese buj (j written for d), budu, bud, but, "the Buddha".Turner, Sir Ralph Lilley. "buddha 9276; 1962–1985". A comparative dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages. Digital Dictionaries of South Asia, University of Chicago. London: Oxford University Press. p. 525. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Warder 2000, p. 45.

- ↑ Buswell 2003, p. 352.

- ↑ Lopez 1995, p. 6.

- ↑ Carrithers 1986, p. 10.

- ↑ Armstrong 2004, p. xii.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Gombrich 1988, p. 49.

- ↑ Smith 1924, pp. 34, 48.

- ↑ Schumann 2003, pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Walshe 1995, p. 268.

- ↑ Collins 2009, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Nakamura 1980, p. 20.

- ↑ Wynne 2007, pp. 8–23, ch. 2.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cousins 1996, pp. 57–63.

- ↑ Schumann 2003, pp. 10–13.

- ↑ Bechert & 1991-1997.

- ↑ Ruegg 1999, pp. 82-87.

- ↑ Narain 1993, pp. 187-201.

- ↑ Prebish 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Gombrich 1992.

- ↑ Uni. Heidelberg.

- ↑ Hartmann 1991.

- ↑ Gombrich 2000.

- ↑ Norman 1997, p. 33.

- ↑ Schumann 2003, p. xv.

- ↑ Wayman 1993, pp. 37–58.

- ↑ Samuels 2010, pp. 140–52.

- ↑ Gethin 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Keown & Prebish 2013, p. 436.

- ↑ Gethin 1998, p. 14.

- ↑ Walsh 1995, p. 20.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Nakamura 1980, p. 18.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Huntington 1986.

- ↑ Gombrich 2002, p. 49.

- ↑ Weise 2013.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Huntington 1988.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Samuel 2010.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel 2002.

- ↑ Malalasekera 1960, pp. 291-292.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Dhammika 1993.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Corless 1989, p. 4.

- ↑

Life of Shakyamuni Buddha, StudyBuddhism

Life of Shakyamuni Buddha, StudyBuddhism

- ↑ Anderson 2013, Kindle Locations 364-367.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Gethin 1998, s.v. Chapter 1, section "Legend of the Buddha".

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Fowler 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ Beal 1883.

- ↑ Cowell 1894.

- ↑ Willemen 2009.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Karetzky 2000, p. xxi.

- ↑ Beal 1875.

- ↑ Swearer 2004, p. 177.

- ↑ Schober 2002, p. 20.

- ↑ Strong 2007, pp. 136–37.

- ↑ Relics associated with Buddha (Wikipedia)

- ↑ Mipham Rinpoche 2002, s.v. paragraphs 21.149-150.

Sources

Printed sources

- Armstrong, Karen (2000), Buddha, Orion, ISBN 978-0-7538-1340-9

- ——— (1883), The Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king, a life of Buddha, Beal, Samuel, transl., Oxford: Clarendon

- Baroni, Helen J. (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism, Rosen

- Beal, Samuel, transl. (1875), The romantic legend of Sâkya Buddha (Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra), London: Trübner

- Bechert, Heinz (ed.) (1991–1997), The dating of the historical Buddha (Symposium), vol. 1-3, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (1993), The Two Traditions of Meditation In Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass

- Buswell, Robert E, ed. (2003), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 1, US: Macmillan Reference, ISBN 0-02-865910-4

- Carrithers, M. (2001), The Buddha: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-02-865910-4

- Collins, Randall (2009), The Sociology of Philosophies, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-67402977-4, 1120 pp.

- Corless, Roger J. (1989), The Vision of Buddhism, Paragon House

- Cousins, LS (1996), "The dating of the historical Buddha: a review article", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 3, Indology, 6 (1): 57–63

- Cowell, Edward Byles, transl. (1894), "The Buddha-Karita of Ashvaghosa", in Müller, Max, Sacred Books of the East (PDF), XLIX, Oxford: Clarendon

- Davidson, Ronald M. (2003), Indian Esoteric Buddhism, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-12618-2

- Dhammika, S. (1993), The Edicts of King Asoka: An English Rendering, The Wheel Publication (386/387), Kandy Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society, ISBN 955-24-0104-6

- Dundas, Paul (2002), The Jains (Google Books) (2nd ed.), Routledge, p. 24, ISBN 978-0-41526606-2, retrieved 25 December 2012

- Eade, JC (1995), The Calendrical Systems of Mainland South-East Asia (illustrated ed.), Brill, ISBN 978-900410437-2

- Epstein, Ronald (2003), Buddhist Text Translation Society's Buddhism A to Z (illustrated ed.), Burlingame, CA: Buddhist Text Translation Society

- Fowler, Mark (2005), Zen Buddhism: beliefs and practices, Sussex Academic Press

- Gethin, Rupert, ML (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press

- Gombrich, Richard F (1988), Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo, Routledge and Kegan Paul

- ——— (1992), "Dating the Buddha: a red herring revealed", in Bechert, Heinz, Die Datierung des historischen Buddha, Symposien zur Buddhismusforschung (in Deutsch), IV (2), Gottingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, pp. 237–59.

- ——— (1997), How Buddhism Began, Munshiram Manoharlal

- ——— (2000), "Discovering the Buddha's date", in Perera, Lakshman S, Buddhism for the New Millennium, London: World Buddhist Foundation, pp. 9–25.

- Grubin, David (Director), Gere, Richard (Narrator) (2010), The Buddha: The Story of Siddhartha (DVD), David Grubin Productions, 27:25 minutes in, ASIN B0033XUHAO

- Hamilton, Sue (2000), Early Buddhism: A New Approach: The I of the Beholder, Routledge

- Hartmann, Jens Uwe (1991), "Research on the date of the Buddha", in Bechert, Heinz, The Dating of the Historical Buddha (PDF), 1, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, pp. 38–39, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-29

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2002), "Hinduism", in Kitagawa, Joseph, The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture, Routledge

- Huntington, John C (1986), "Sowing the Seeds of the Lotus" (PDF), Orientations, September 1986: 46–58, archived from the original (PDF) on Nov 28, 2014

- Jones, JJ (1949), The Mahāvastu, Sacred Books of the Buddhists, 1, London: Luzac & Co.

- ——— (1952), The Mahāvastu, Sacred Books of the Buddhists, 2, London: Luzac & Co.

- ——— (1956), The Mahāvastu, Sacred Books of the Buddhists, 3, London: Luzac & Co.

- Jong, JW de (1993), "The Beginnings of Buddhism", The Eastern Buddhist, 26 (2)

- Kala, U (2006) [1724], Maha Yazawin Gyi (in Burmese), 1 (4th ed.), Yangon: Ya-Pyei, p. 39

- Karetzky, Patricia (2000), Early Buddhist Narrative Art, Lanham, MD: University Press of America

- Katz, Nathan (1982), Buddhist Images of Human Perfection: The Arahant of the Sutta Piṭaka, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Keown, Damien; Prebish, Charles S (2013), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Routledge

- Laumakis, Stephen (2008), An Introduction to Buddhist philosophy, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52185413-9

- Lopez, Donald S (1995), Buddhism in Practice (PDF), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-04442-2

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1960), Dictionary of Pali Proper Names, Vol. 1, London: Pali Text Society/Luzac

Mipham Rinpoche (2002), Gateway to Knowledge, vol. III, translated by Kunsang, Erik Pema, Rangjung Yeshe Publications

Mipham Rinpoche (2002), Gateway to Knowledge, vol. III, translated by Kunsang, Erik Pema, Rangjung Yeshe Publications- Nakamura, Hajime (1980), Indian Buddhism: a survey with bibliographical notes, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0272-8

- Narada (1992), A Manual of Buddhism, Buddha Educational Foundation, ISBN 967-9920-58-5

- Narain, A.K. (1993). "Book Review: Heinz Bechert (ed.), The dating of the Historical Buddha, part I". Journal of The International Association of Buddhist Studies. 16 (1): 187–201.

- Norman, KR (1997), A Philological Approach to Buddhism (PDF), The Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai Lectures 1994, School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London)

- Prebish, Charles S. (2008), "Cooking the Buddhist Books: The Implications of the New Dating of the Buddha for the History of Early Indian Buddhism" (PDF), Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 15: 1–21, archived from the original (PDF) on Jan 28, 2012

- Rockhill, William Woodville, transl. (1884), The life of the Buddha and the early history of his order, derived from Tibetan works in the Bkah-Hgyur and Bstan-Hgyur, followed by notices on the early history of Tibet and Khoten, London: Trübner

- Ruegg, Seyford (1999). "A new publication on the date and historiography of Buddha´s decease (nirvana): a review article". Bulletin of the Schoool of Oriental and Afrikan Studies, University of London. 62 (1): 82–87.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra. Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Schmithausen, Lambert (1981), "On some Aspects of Descriptions or Theories of 'Liberating Insight' and 'Enlightenment' in Early Buddhism", in von Klaus, Bruhn; Wezler, Albrecht, Studies on Jainism and Buddhism (Schriftfest for Ludwig Alsdorf) (in Deutsch), Wiesbaden, pp. 199–250

- Schober, Juliane (2002), Sacred biography in the Buddhist traditions of South and Southeast Asia, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Schumann, Hans Wolfgang (2003), The Historical Buddha: The Times, Life, and Teachings of the Founder of Buddhism, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 812081817-2

- Shimoda, Masahiro (2002), "How has the Lotus Sutra Created Social Movements: The Relationship of the Lotus Sutra to the Mahāparinirvāṇa-sūtra", in Reeves, Gene, A Buddhist Kaleidoscope, Kosei

- Skilton, Andrew (2004), A Concise History of Buddhism

- Smith, Peter (2000), "Manifestations of God", A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, ISBN 1-85168-184-1, 231 pp.

- Smith, Vincent (1924), The Early History of India (4th ed.), Oxford: Clarendon

- Strong, John S (2007), Relics of the Buddha, Motilal Banarsidass

- Swearer, Donald (2004), Becoming the Buddha, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

- Thapar, Romila (2002), The Penguin History of Early India: From Origins to AD 1300, Penguin

- Turpie, D (2001), Wesak And The Re-Creation of Buddhist Tradition (PDF) (master's thesis), Montreal, QC: McGill University, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-04-15

- Twitchett, Denis, ed. (1986), The Cambridge History of China, 1. The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC – AD 220, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24327-0

- Upadhyaya, KN (1971), Early Buddhism and the Bhagavadgita, Dehli, IN: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 95, ISBN 978-812080880-5

- Vetter, Tilmann (1988), The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism, Brill

- Waley, Arthur (Jul 1932), "Did Buddha die of eating pork?: with a note on Buddha's image", Melanges Chinois et bouddhiques, NTU, 1931–32: 343–54, archived from the original on Jun 3, 2011

- Walshe, Maurice (1995), The Long Discourses of the Buddha. A Translation of the Digha Nikaya, Boston: Wisdom Publications

- Warder, AK (2000), Indian Buddhism, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Wayman, Alex (1997), Untying the Knots in Buddhism: Selected Essays, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 812081321-9

- Weise, Kai; et al. (2013), The Sacred Garden of Lumbini – Perceptions of Buddha's Birthplace (PDF), Paris: UNESCO, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-30

- Willemen, Charles (2009), Buddhacarita: In Praise of Buddha's Acts (translation), Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, ISBN 978-1886439-42-9

- Wynne, Alexander (2007), The Origin of Buddhist Meditation (PDF), Routledge, ISBN 0-20396300-8

Online souces

- ↑ Berzin, Alexander (April 2007). "Indian Society and Thought before and at the Time of Buddha". Berzin archives. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Vergano, Dan (25 November 2013). "Oldest Buddhist Shrine Uncovered In Nepal May Push Back the Buddha's Birth Date". National Geographic. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Gombrich, Richard (2013), Recent discovery of "earliest Buddhist shrine" a sham?, Tricycle.

- ↑ Tan, Piya (2009-12-21), Ambaṭṭha Sutta. Theme: Religious arrogance versus spiritual openness (PDF), Dharma farer.

- ↑ Davids, Rhys, ed. (1878), Buddhist birth-stories; Jataka tales. The commentary introd. entitled Nidanakatha; the story of the lineage. Translated from V. Fausböll's ed. of the Pali text by TW Rhys Davids (new & rev. ed.).

- ↑ "Lumbini, the Birthplace of the Lord Buddha". UNESCO. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ↑ "The Astamahapratiharya: Buddhist pilgrimage sites". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ "Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhara". UW Press. Retrieved 4 September 2008.

- ↑ Lopez Jr., Donald S. "The Buddha's relics". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Further reading

The Buddha

- Thich Nhat Hanh (1991), Old Path White Clouds, Parallax Press

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikku (1992). The Life of the Buddha According to the Pali Canon (3rd ed.). Kandy, Sri Lanka: Buddhist Publication Society.

- Wagle, Narendra K (1995). Society at the Time of the Buddha (2nd ed.). Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-817154553-7.

Early Buddhism

- Rahula, Walpola (1974). What the Buddha Taught (2nd ed.). New York: Grove Press.

- Vetter, Tilmann (1988), The Ideas and Meditative Practices of Early Buddhism, Brill

Buddhism general

- Kalupahana, David J. (1994), A history of Buddhist philosophy, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Robinson, Richard H.; Johnson, Willard L; Wawrytko, Sandra A; DeGraff, Geoffrey (1996). The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

External links

A sketch of the Buddha's Life, Access to Insight

A sketch of the Buddha's Life, Access to Insight Indian Society and Thought at the Time of Buddha, StudyBuddhism

Indian Society and Thought at the Time of Buddha, StudyBuddhism- Life of the Buddha (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

| This article includes content from Gautama Buddha on Wikipedia (view authors). License under CC BY-SA 3.0. |